California Governor Jerry Brown just won a big victory in his efforts to fight climate change, but Canada’s Ontario province says its been pushing him to go further.

As the two sides hammer out details of a long-planned merger of their carbon markets, Ontario minister for environment Glen Murray says there are holes in the Golden State’s system that may allow oil refiners and power generators to spew carbon dioxide into the air on the cheap. Murray is recommending stricter rules that, he says, will keep companies from hoarding permits that allow them to pollute for years.

“You just don’t want backdated allowances floating around the market,” Murray said before the vote. “We know we have the option to retire them even if they don’t.”

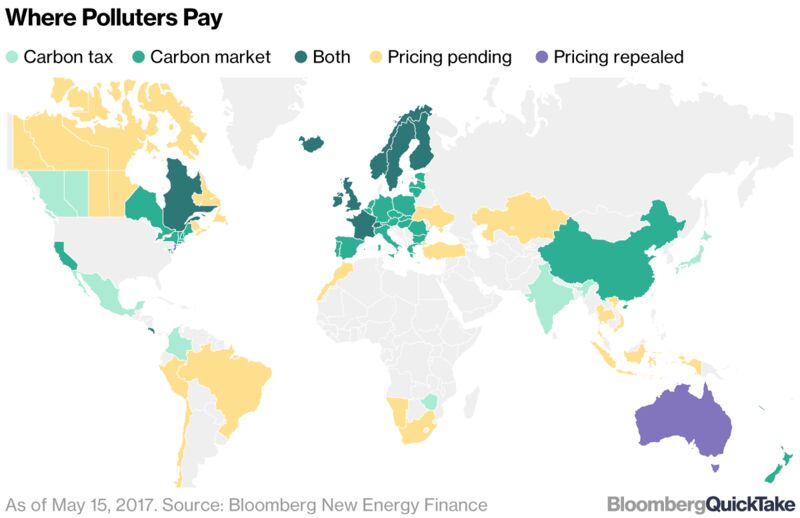

The split illustrates the challenge local and national leaders around the world face in crafting policies that curb emissions while managing costs. And their solutions are being closely watched now that President Donald Trump has withdrawn the U.S. from the Paris climate accord. California and New York are among states that have joined corporate giants from Google to Wal-Mart Stores Inc. in vowing to continue to work with other countries to uphold the pact.

Legislation extending California’s economy-wide greenhouse gas program through 2030, unveiled by Brown last week, passed both state houses Tuesday. Businesses, including oil companies, pressed for an extension saying the program is the most cost-effective way to meet the state’s 2030 target of reducing greenhouse gases to 40 percent below 1990 levels.

California allows emitters to bank unused carbon permits, giving them more time to release emissions without paying extra. Ontario would have them sunset, after which they’d lose all value. Forthcoming rules may still change the value of allowances through 2030, including possible new regulations on how long the permits can be used and whether some might be placed into a reserve to deal with oversupply, according to Alex Rau, a carbon trader with Abatement Capital LLC in San Francisco.

“This is an extension rather than a wholesale reworking of climate policy,” Rau said. “It’s a very good outcome for the state and climate policy in general.”

Market Merger

The carbon market merger, which includes Quebec, has been planned since 2015 and Murray said his objections don’t amount to a deal breaker. Still, changes he is seeking would make the program more aggressive and attract more capital as pension funds and other investors are increasingly steering away from fossil fuels.

“We’re not longing for the days of coal and going back to an economy that doesn’t exist,” Murray said. “Our view would be different to some of the right wing in the U.S., which has a nostalgic economic policy. Going down that road would be a dead end — we see the future as an economy based on resource recovery, not new resource extraction.”

Dave Clegern, a spokesman for the California Air Resources Board, declined to comment on Murray’s request.

Merging carbon markets lowers costs by giving emitters more options to reduce greenhouse gases. States and Canadian provinces have discussed cooperation since 2007 when Arizona, California, New Mexico, Oregon and Washington kicked off an effort to design a regional market.

“Ontario is committed to partnering with California and Quebec as we work together to responsibly fight climate change and remain confident that a linked system remains the best option to reduce greenhouse gas and grow our economy,” David Mullock, a spokesman for Murray, said by email Tuesday.

Climate Investment

Clear and consistent climate policies will draw more investment, Torben Moeger Pedersen, chief executive officer of PensionDanmark, said by phone. PensionDanmark, with $33 billion under management, is exploring offshore wind projects in Canada.

“Regions with a high level of ambition will be able to get substantial funding for their programs,” Pedersen said.

The legislative package in California follows weeks of negotiations with industry, labor and environmental groups, some of which are urging lawmakers to reject the measure, saying it’s too friendly to polluters.