The revolution in electric vehicles set to upturn industries from energy to infrastructure is also creating winners and losers within the world’s biggest metals markets.

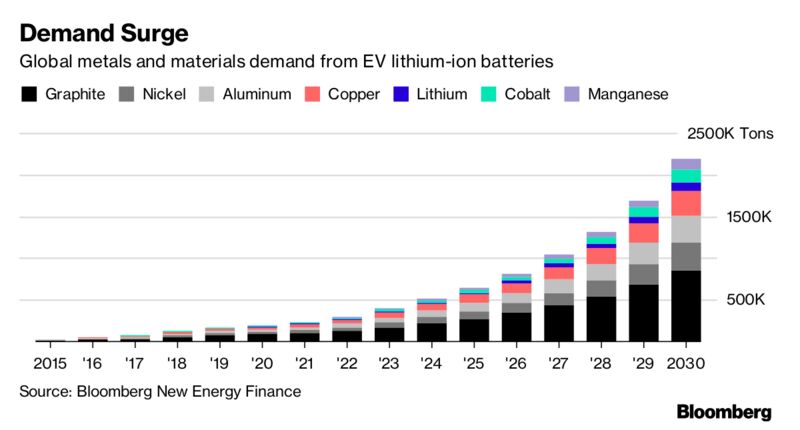

While some of the largest diversified miners like Glencore Plc argue fossil fuels such as coal and oil still play a crucial role supplying energy needs, they’ll also benefit the most from a move to electric cars, requiring more cobalt, lithium, copper, aluminum and nickel.

The outlook for greener transportation got a boost this year as the U.K. joined France and Norway in saying it would ban fossil-fuel car sales in coming decades. That’s as Volvo AB announced plans to abandon the combustion engine and Tesla Inc. unveiled its latest, cheaper Model 3. Such vehicles will outsell their petroleum-driven equivalents within two decades, Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates.

“For some of the metals, it’s a complete game changer,” said Simona Gambarini, a commodities economist at Capital Economics Ltd. in London. “We’ve already seen a big impact on some metals like cobalt and lithium, which have soared over the past couple of years.”

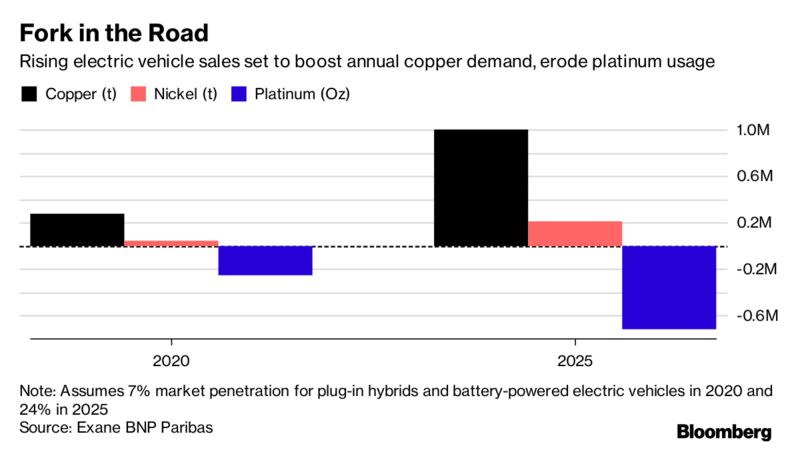

Electric cars contain about three times more copper than a regular vehicle, according to Glencore. Even more is needed for charging stations, with Exane BNP Paribas seeing such infrastructure adding about 5 percent to demand by 2025. Lithium, cobalt, graphite and manganese used in batteries will also see additional demand.

Copper and Cobalt

Glencore will get a boost as rising electric-vehicle sales lend support to copper prices, as well as from its position as the world’s largest cobalt producer, according to Jefferies Group LLC. Freeport-McMoRan Inc. and First Quantum Minerals Ltd. are also top picks for long-term investors looking to benefit from the trend, the brokerage said in a note Tuesday.

Markets are responding. Cobalt has surged 70 percent on the London Metal Exchange this year, after jumping 37 percent in 2016. Lithium prices have extended gains in recent years. Copper is also up 14 percent in 2017 on signs of resurgent economic growth, particularly in China.

On the flipside, lead producers such as Recylex SA and Campine SA may need to adapt operations to the new era. The main end-use for lead is in starter batteries for petrol and diesel engines. Electric vehicles, by contrast, are powered by lithium-ion units.

“It’s a serious risk for lead demand, unless you find different applications to make up for the decline,” said Michael Widmer, head of metals market research at Bank of America Merrill Lynch in London.

Lithium vs Lead

Yet with lead prices up 17 percent this year, the best of any major industrial metal traded in London, investors see only distant risks.

“I’m not so sure things will turn out” so badly for lead, as cheap oil prices will help keep conventional cars competitive, said Herwig Schmidt, head of sales at metals brokerage Triland Metals Ltd. If demand for lead does drop, it will do so gradually, he said. “Maybe that will be the case in 10 years or so.”

In the meantime, stricter emissions rules could raise demand for hybrid cars that rely on advanced lead-intensive batteries to cope with frequent engine stops and starts, according to the International Lead and Zinc Study Group.

It’s not just shifts in use of batteries and wires that are forcing change.

Lightweight metals like aluminum are replacing steel to allow cars to travel further on less power. That already expanded demand by about 1.6 million metric tons, or 2.7 percent of global output, from 2013 to 2016 in a trend that’s likely to accelerate, Widmer said.

Aluminum vs Steel

Aluminum is up 14 percent this year as rising use by automakers has run into supply curbs in China, pushing the market into deficit.

Steelmakers are fighting back. AK Steel Holding Corp. has teamed up with General Motors Co. to try to use nanotechnology to make lightweight vehicle bodies. ArcelorMittal and Tata Steel Europe are also among those developing lighter, stronger alloys to fend off the competition.

“The development of ultra high-strength steel is meant to address that,” said Sylvain Brunet, an analyst at Exane BNP Paribas. There’s been “some success in Europe.”

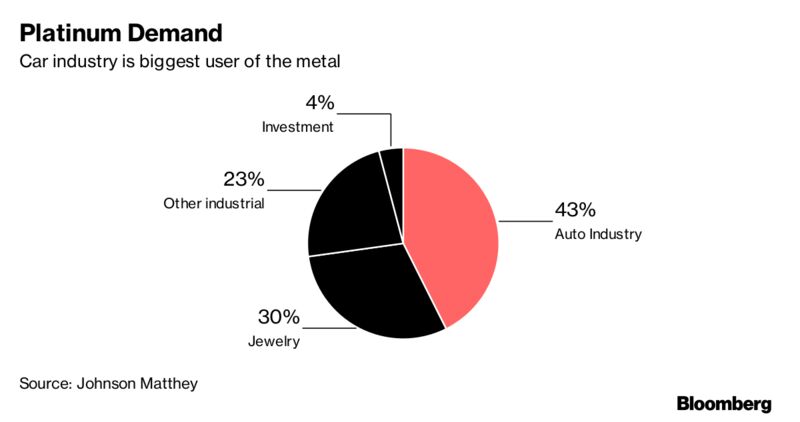

Platinum may also struggle to cope with the end of petroleum.

Almost half the precious metal used last year was sold to the auto industry for use in catalytic converters to curb diesel pollution, according to research from Johnson Matthey Plc, one of its top refiners.

“A lot of commodities that are in demand right now, like oil and platinum, may not be in demand in the future,” said Bernard Dahdah, a commodities analyst at Natixis SA in London. “It’s not that commodities overall will become less relevant, but we will see a reshuffling in terms of what is important in the next 15 years.”

The platinum industry sees a continued need for converters in diesel-hybrid engines. Umicore SA, a maker of raw materials for batteries and engine catalysts, expects hybrids to still outnumber full-electric cars in 2025, Chief Executive Officer Marc Grynberg said Monday.

“Given the expected evolution of battery costs, there may still be an advantage to buying a hybrid,” he said.

Fuel-cell vehicles being developed by Toyota Motor Corp. and Hyundai Motor Co. that rely on platinum as a catalyst to generate energy from hydrogen promise the greatest opportunity for demand growth in the next 10 years, according to the World Platinum Investment Council lobby.

Yet, until such technology has been proven commercially, the industry is at risk from the shift away from fossil fuels.

“Diesel looks set to be the clear loser out of this substitution towards electric vehicles,” said Brunet at Exane BNP Paribas.

German carmakers, fighting for diesel’s future, faced a setback last month after a Stuttgart court ruled in favor of banning the technology in the home city of Mercedes-Benz and Porsche.

Perhaps the most immediate danger from electric vehicles, though, is to analysts’ predictions. Given the tectonic shift away from oil and the competing technologies to replace the fossil fuel, the outlook for demand from the auto industry has never been so clouded.

“What it comes down to is the extent to which electric vehicles gain popularity,” said Bank of America’s Widmer. “For metals like copper and nickel, if you underestimate electric vehicle sales by one percentage point, you can add one percentage point to global demand.”