Indian solar projects banking on a continuous supply of ever-cheaper panels are now under threat as China’s appetite props up prices.

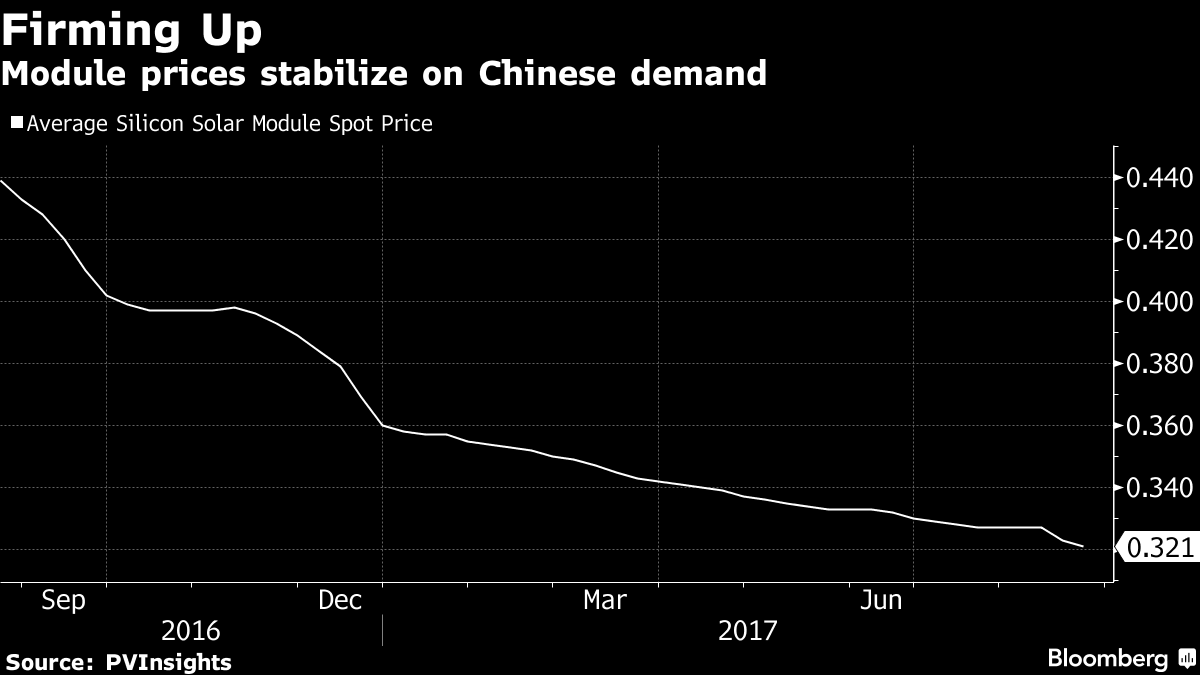

The global spot market price for solar panels in the second quarter fell at the slowest pace since the three months ended in December 2015, according to data compiled by PVinsights. While the decline has picked up slightly this month, they’re down 10 percent since the beginning of the year, compared with a 35 percent drop in 2016.

The slowdown is complicating plans for solar developers in India, who were anticipating the cost of their panels would fall more quickly and are now facing an unexpected reduction in their returns. That’s making the industry more cautious about future developments, adding a hurdle to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ambition for quick growth in clean-energy.

“If the current module prices do not go down, the developers would take a hit on their expected returns as these bids carry razor-thin margins,” said Allen Tom Abraham, a New Delhi-based analyst with Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

China, which accounts for more than 80 percent of global solar panel production, is also the biggest market for solar panels. It added 23 gigawatts of new solar capacity in the first half of this year, almost double the 13 gigawatts India has installed to date. The government in China is seeking to double installations by the end of 2020.

In India, developers have been bidding aggressively in auctions for power-purchase contracts, offering regulators some of the cheapest power from photovoltaics anywhere. Those calculations were made in anticipation of further sharp declines in PV prices. Now, developers are seeing their returns dwindle.

In May, companies promised to supply solar power for as little as 2.44 rupees (or 3.8 cents) a kilowatt-hour, meaning India would have some of the cheapest solar power in the world. Those offers were based on the assumption that module prices would fall, according to Sujoy Ghosh, country head for India at Tempe, Arizona-based First Solar Inc.

Long-term returns for projects awarded at the May auction prices are in the single digits, meaning free cash flow will be difficult to generate given India’s high cost of capital, Ghosh said.

Price Concerns

China’s demand and a reduction in the production of polysilicon, a raw material used in most panels, are contributing to the firming of prices, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

“Suppliers are not willing to supply at rates assumed by some of the Indian developers,” Anish De, partner and head for infrastructure strategy and operations at KPMG, said in a phone interview. “Anything under a three-rupee-a-unit tariff is going to be questionable."

It’s not just India that’s seeing panel prices inch higher. They’ve also risen about 20 percent in the U.S. since Suniva Inc., based in Norcross, Georgia, asked the government to impose duties on solar panels imported from China, according to BNEF’s third-quarter market outlook for the solar industry published on Aug. 18.

India also recently started an anti-dumping investigation into China-made cells to protect domestic manufacturers, which are too small to meet local demand. Chinese solar goods have undercut prices in India by almost 40 percent, according to the Indian Solar Manufacturers Association, the industry body which asked for an investigation.

Hedging Risks

While China offered to ease trade friction, political tensions linger between the two nations over a border dispute in the Himalayas.

Trade disputes aside, Indian developers who bid in auctions based on prices in the low 20 cents per watt are concerned, according to BNEF.

“After hedging all the risks, it was difficult for us to match the bids that won at the solar auctions,” said Rajiv Ranjan Mishra, managing director at the Indian arm of Hong Kong-based CLP Holdings Ltd. CLP sat out previous auction rounds.

Others say projects bid at low tariff levels are ill-equipped to face risks such as cost and time overruns or payment delays, impacting their economic viability.

“The margin of safety would eventually come back as companies start experiencing issues during construction of projects,” Sanjay Aggarwal, managing director for India at Finnish power utility Fortum OYJ, said by phone. "When I say margin of safety, one assumes on a piece of paper that everything would go as predicted and it never happens."