It’s no secret that oil majors are among the biggest corporate emitters of pollution. What may be surprising is that they’re reducing their greenhouse-gas footprints every year, actively participating in a trend that’s swept up most corporate behemoths.

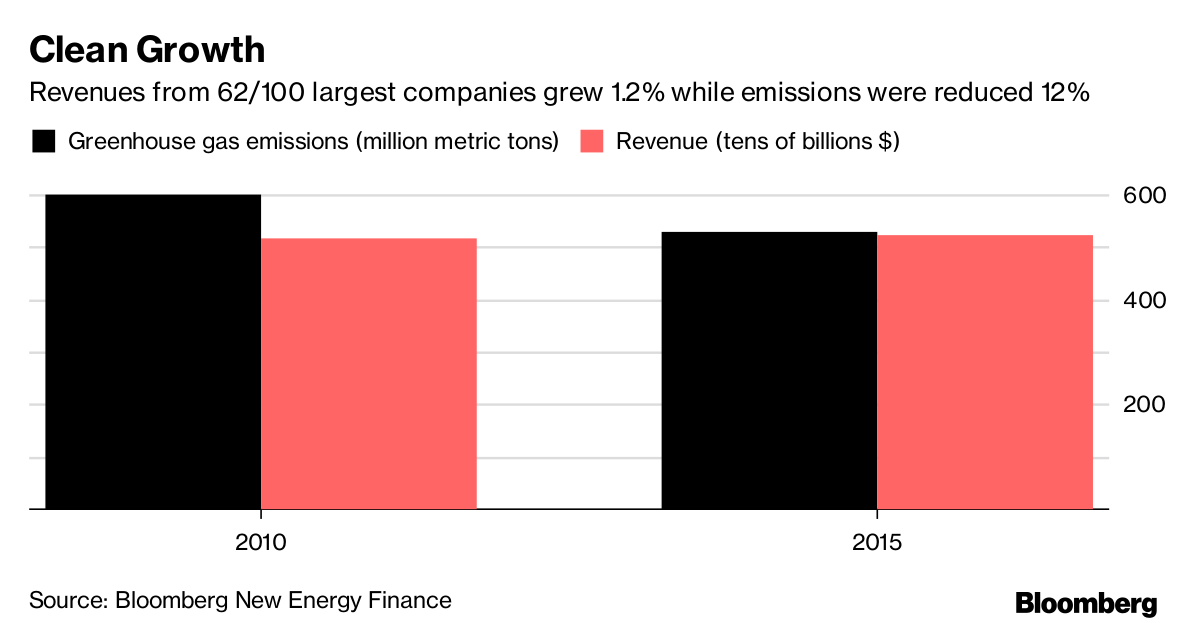

Sixty-two of the world’s 100 largest companies consistently cut their emissions on an annual basis between 2010 and 2015, with an overall 12 percent decline during that period, according to a report from Bloomberg New Energy Finance released ahead of its conference in London on Monday.

The findings suggest the most polluting industries had started fighting climate change before President Donald Trump took office and signaled he’d back out of U.S. participation in the Paris accord on limiting fossil fuel emissions. Now, as European officials say the White House may water down its commitment to Paris instead of scrapping the deal, the BNEF report suggests industry is scaling back the emissions.

“It doesn’t matter if Trump stays in Paris; it’s irrelevant as the states and big corporations are moving forward with clean energy,” Peter Terium, chief executive officer of the German power generator Innogy SE, said on the sidelines of the BNEF conference on Monday. “They’re not waiting. We’re seeing renewable energy becoming more and more competitive opposite fossil fuels like coal.”

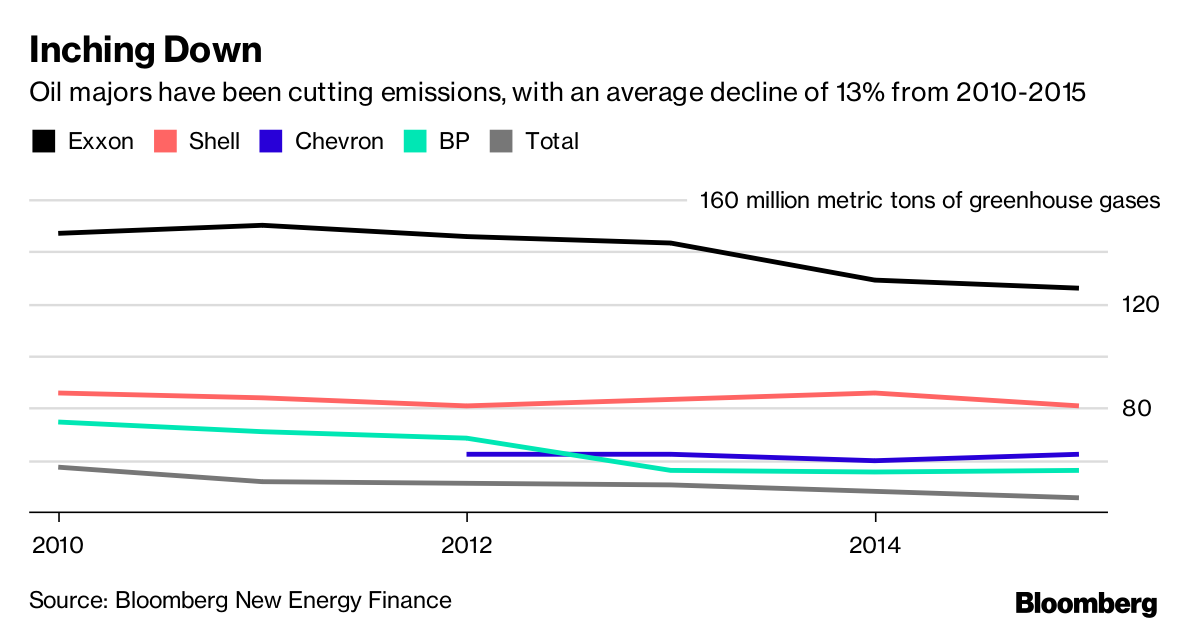

The five biggest oil companies — Exxon Mobil Corp., Royal Dutch Shell Plc, Chevron Corp., BP Plc and Total SA — collectively curbed their pollution by an average of 13 percent between 2010 and 2015, the report said. BP cut the most at 25.5 percent. Exxon, the largest emitter among listed companies, pushed it down by 14 percent.

The report shows a reverse from previous decades, when scientific warnings about climate change were new and the companies behind the most emissions lobbied policymakers to ignore the issue. As mega-storms like Hurricane Irma this year and Sandy in 2012 raised consciousness about the issue, companies even in the oil business have taken steps to rein in pollution and associate themselves with the green agenda.

The reductions recorded by the 100 top companies saved 70.7 million tons of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, about as much as Israel emits in a year. Because emissions data takes so long to compile, 2015 is the latest year covered.

“This is a reflection of growing pressure from shareholders, investor groups and civil society for more disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions, as well as setting reduction targets,” said Laura McIntyre-Brown, analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance and the author of the report. “There’s also an evident trend of increased emissions disclosure among many of the biggest companies.”

Oil’s View

Exxon said it has spent about $8 billion since 2000 to deploy low-emission energy equipment across its operations and that it’s conducting and supporting research on technologies to make further cuts. An official at Shell said its new energy business is more focused on “good projects” rather than meeting a target. A press officer at Total said the figures in the BNEF report were accurate. BP and Chevron didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

The corporations in the BNEF survey had combined revenue of more than $5 trillion. That’s more than the gross domestic product of every country except the U.S. and China, according to data from the World Bank. They wield immense power over the global economy and are having a sizable impact on the state of the environment, both from their operations and through corporate lobbying.

While some of the reduction from the big oil companies is probably due to the crash in oil prices that began in 2014, leading to lower activity across the energy industry, all five majors have enacted climate and efficiency policies, as well as anti-pollution measures, the report said.

As the energy sector pollutes more than any other industry, even marginal gains can have a significant impact. Big Oil collectively saved 56.7 million tons of greenhouse gases between 2010 and 2015. That sum excludes Chevron, which only started reporting in 2012.

While progress has been made, there isn’t evidence yet that the oil business could break the link between its revenue and the pollution it emits, the report concluded. While the energy industry cut emissions, its revenue declined by 26 percent in the same time period.

Outside the energy industry, companies collectively have managed to pare back emissions while boosting sales. Collective revenue for the 62 companies covered in the report rose 1.2 percent while emissions fell 12 percent. In all, 71 million metric tons of greenhouse gases were avoided while sales gained by $61 billion. Health providers and consumer-product makers led the trend.

“If you think about the oil and gas industry, use of oil and gas for combustion creates emissions,” said Rick Wheatley, executive vice president of new growth at Xynteo Ltd., a consultancy that advises Shell, Statoil ASA and Eni SpA on sustainability and long-term planning. “If diversification into other kinds of energy is on the table, then I think it’s absolutely possible to decouple.”

The trend may continue after almost 200 countries agreed in Paris in 2015 to limits on fossil-fuel emissions, said Sean Kidney, chief executive officer of the Climate Bond Initiative, an organization that promotes green bonds sold to pay for environmental projects.

“The Paris agreement has been extraordinarily successful in establishing a new consensus,” Kidney said. ‘‘There’s a sense of future certainty developing which is influencing decision-making in the corporate sector.”