John Lippert and Ryan Beene

California may re-open discussions on its greenhouse gas limits for cars and trucks for 2025, so long as automakers and the Trump administration embrace significantly tougher targets the state is seeking for later years.

Automakers have “a whole laundry list of things they’ve asked for” to ease the state’s standards leading up to 2025, and California is willing to at least discuss reviving talks, Mary Nichols, chair of the California Air Resources Board, said in an interview Friday at Bloomberg News headquarters in New York. Michael Catanzaro, a White House special assistant, called her recently to get conversations with the administration started, she said.

“The price of getting us to the table is talking about post-2025,” she said. “California remains convinced that there was no need to initiate this new review of the review and that the technical work was fully adequate to justify going ahead with the existing program, but we’re willing to talk about specific areas if there were legitimate concerns the companies raised — in the context of a bigger discussion about where we’re going post-2025.”

Talk of a possible three-way negotiation between California, carmakers and the federal government comes after President Donald Trump’s administration reinstated in March a review of national greenhouse-gas rules that run through 2025, which he said “would have destroyed” the auto industry. California could choose to keep its rules unchanged even if the federal targets are loosened. But doing so would create headaches for carmakers dealing with a patchwork of legislation, and it would risk raising the ire of Trump and the industry as California tries to push through tougher targets for 2030.

the idea of tougher emissions targets for 2030, Nichols said. In an August speech, Mitch Bainwol, president of the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, said his group — which includes General Motors Co., Volkswagen AG and Toyota Motor Corp. — would consider the idea, too.

“We want to collaborate on a data-driven review with California, the administration and other stakeholders to find a good path forward,” Bainwol said in reacting Friday to Nichols’ comments.

A message seeking comment from Catanzaro wasn’t immediately returned.

In the interview, Nichols said she would want the Environmental Protection Agency, and not just the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, to participate, since this would ensure that the talks focus on greenhouse gases and not just fuel economy. She said she has some sympathy for automakers’ request to scrap an Obama-era rule that, starting in 2022, would hold them accountable for emissions that occur when the electricity for their battery-powered vehicles is being generated.

Nichols said she’s not sympathetic to various other forms of potential relief, like cutting existing targets for 2021, pushing the current 2025 targets to a later date, or watering down zero-emission vehicle targets in states like New York and Massachusetts that have opted to follow the California approach.

“A final agreement will be difficult, but the broad interests of both sides are aligned to figure something out,” said Robbie Diamond, president of a non-profit advocacy group called Securing America’s Future Energy. “The federal government wants flexibility so the companies can afford to invest in the modern world of mobility. California wants its targets to be maintained over a longer period, but also needs to be worried about costs that can lead to consumer and political backlash.”

So far, Trump hasn’t launched what could be his most potent weapon — a court challenge to California’s special authority to write its own pollution rules, which dates back to the 1970 Clean Air Act. A compromise today could help prevent a court showdown later.

“If there’s a way they can keep us all united without having to roll over California, they’d like that,” Nichols said of her impressions of the White House’s position.

The federal government in 2011 originally agreed to greenhouse gas targets that mirror California’s, boosting fuel economy to an average of more than 50 miles per gallon by 2025. When Trump overturned an Obama EPA decision to uphold the standards on the books earlier this year, automakers praised Trump’s move.

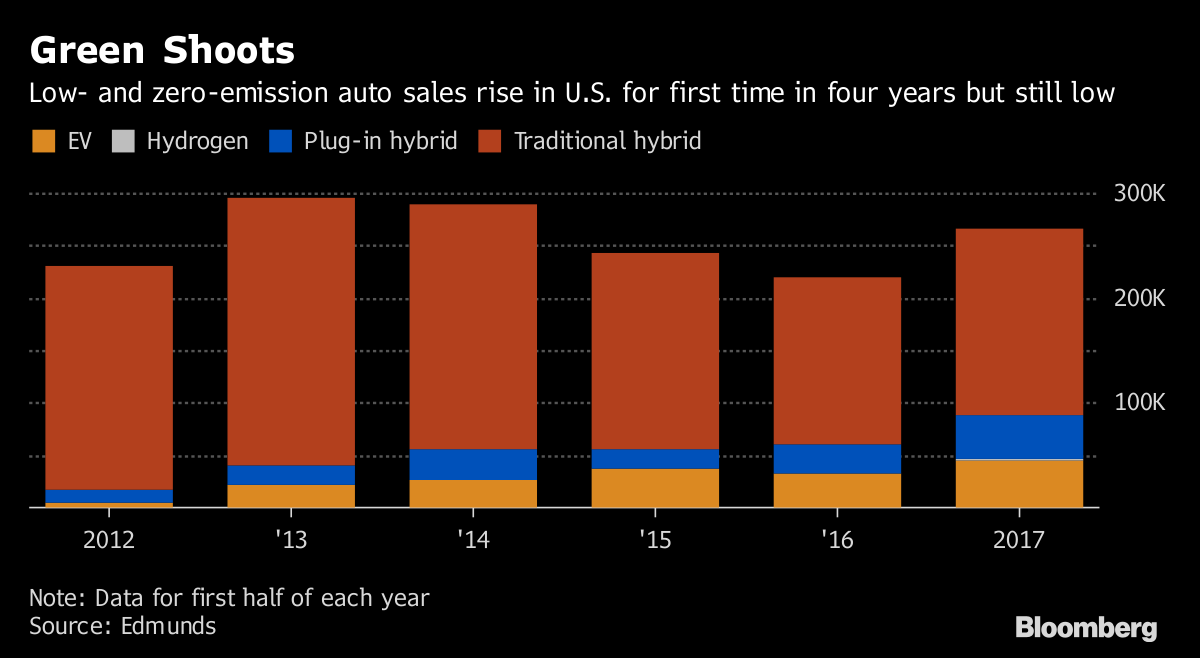

But carmakers don’t want changes at the federal level to create a rift with California and the handful of states who’ve adopted the same targets, fearing costly discrepancies if emissions standards diverge. Pressure for a compromise is also building because, even in California, zero-emission vehicle sales have been stuck at about three percent since 2014.

“I really feel like if the industry folks are as ready as I think they are to talk about future standards, it shouldn’t be all that hard,” Nichols said. “But there are differences in the kind of relief they want.”

Nichols said she expects three-way talks between California, the administration and automakers to begin soon in order to influence a formal report on fuel economy and emissions that the Trump administration is planning for April.

While the state is willing to at least discuss compromise in the short term, California has no intention of retreating from its legislative mandate to cut carbon dioxide emissions to 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, Nichols said. California Governor Jerry Brown and the Air Resources Board have vowed to remain a bulwark against the president’s push for environmental deregulation, and Nichols said long-term goals haven’t changed.

Automakers can’t abandon the cleaner-car goals entirely either, since major car markets China and the European Union are now contemplating their own zero-emission vehicle mandates modeled after California’s. China said this month it will set a deadline for automakers to end sales of fossil-fuel-powered vehicles, becoming the biggest market to do so and driving global demand for battery-operated autos.