Written by Jeanette Rodrigues. This article first appeared in Bloomberg News.

Consumption was India’s big story. Its 1.3 billion population was expected to guzzle everything from iron to iPhones, driving global growth and cheering investors such as Apple Inc. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

For a while everything seemed smooth. Indians were the world’s most confident consumers and the $2 trillion economy was the fastest-growing big market. Then, last November, Prime Minister Narendra Modi voided 86 percent of currency in circulation, worsening a slowdown that had started earlier in the year. Climbing global oil prices and a tightening Federal Reserve could also complicate domestic policy making.

“There are a number of uncertainties which are clouding the short-term outlook of the Indian economy,” said Kaushik Das, Mumbai-based chief economist at Deutsche Bank AG. “Risk of policy error remains high.”

Consumption

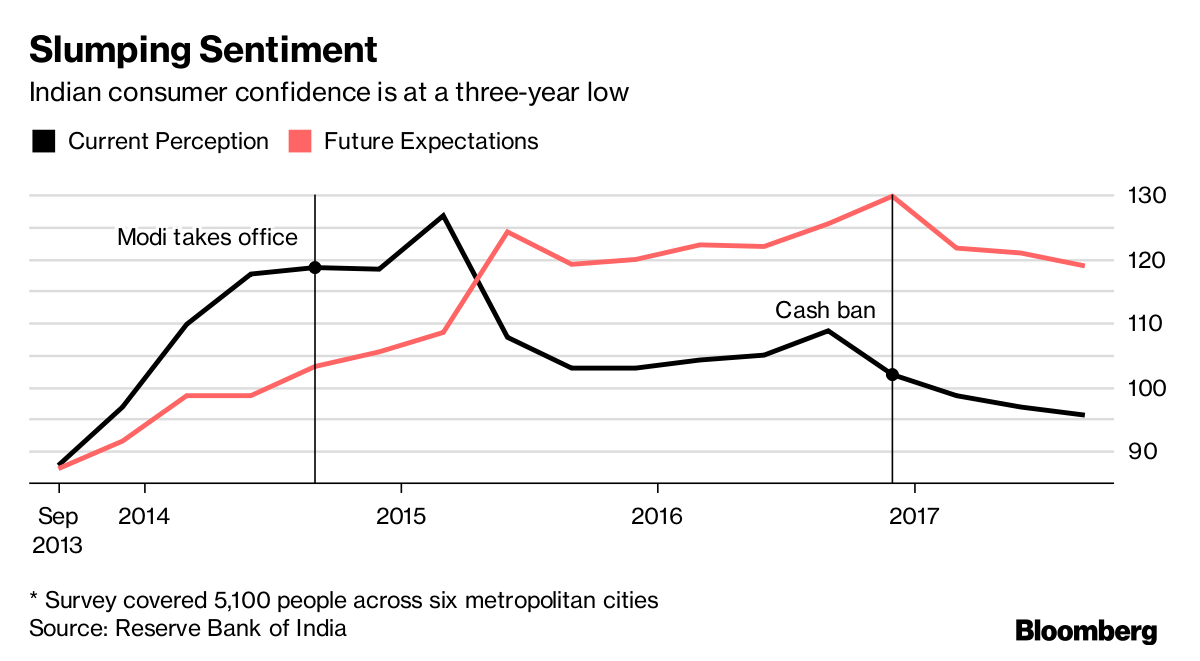

Indians fell off the top of Mastercard’s Asia Consumer Confidence Index in the first half of 2017, and a report from the nation’s central bank last week confirmed the bleak outlook. About 27 percent of Indians surveyed said incomes have fallen, pushing overall sentiment into the “pessimistic zone.” Employment “has been the biggest cause of worry,” the Reserve Bank of India said.

Jobs

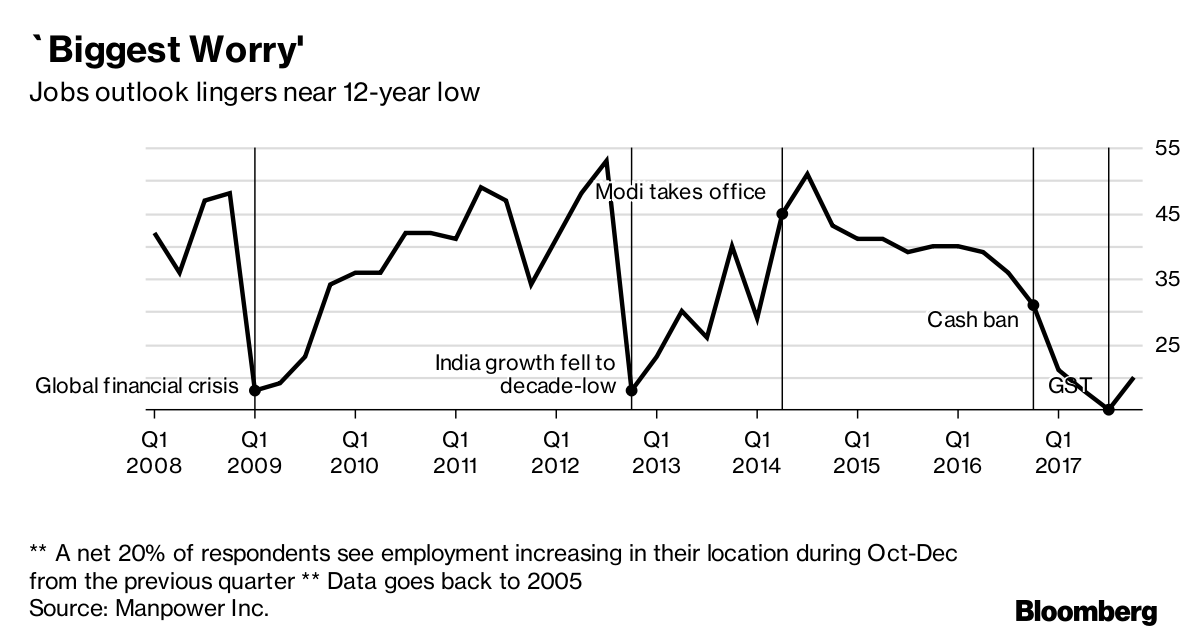

Convincing Indians to consume would first require assuring them they’ll have a job. It won’t be easy for Modi to do so. Manufacturing jobs are forecast to fall about 30 percent this year and broader surveys show the hiring outlook is near a 12-year low. There was an absolute decline in employment between March 2014 and 2016, “perhaps happening for the first time in independent India,” the Economic & Political Weekly journal said this month.

Investment

The jobs scenario is gloomy because companies — bogged down by bad debt and poor demand — aren’t building more factories. Projects worth 512 billion rupees ($7.8 billion) were completed between July to September, the lowest since Modi came to power in 2014, according to data from the Mumbai-based information company Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. The value of fresh investment proposals from the private sector fell to the lowest in 15 quarters and in terms of absolute number of proposals this is the lowest in 13 years.

Loans

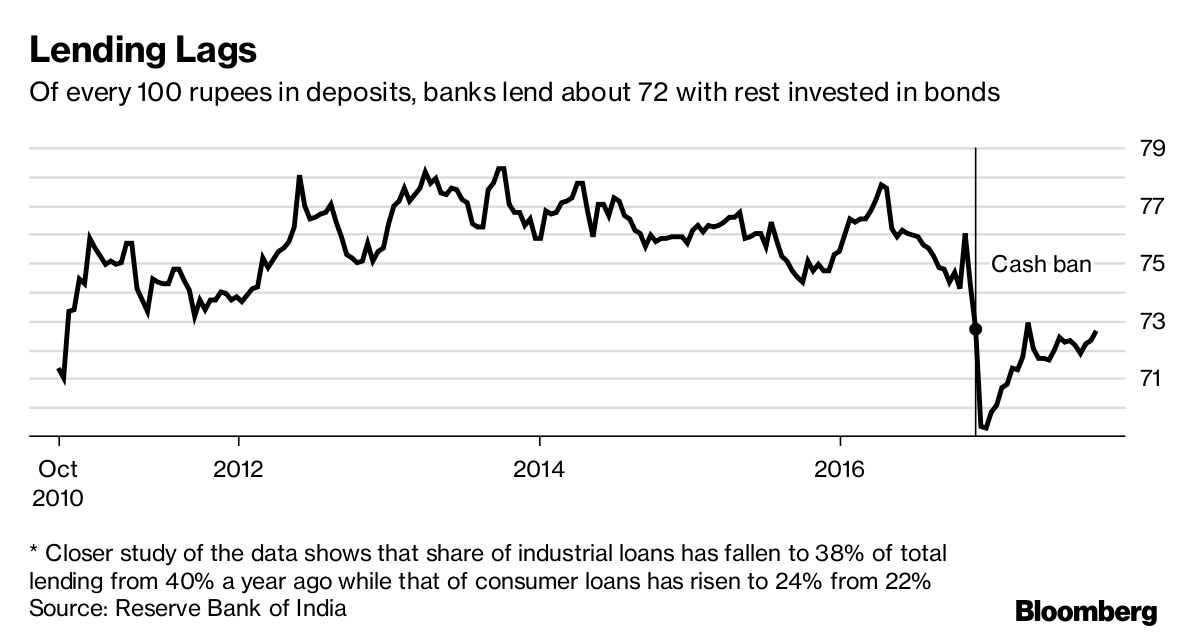

Some economists, such as Abhishek Gupta at Bloomberg Intelligence, say that high real rates are impeding private investment and increasing non-performing assets at banks. This inhibits lending, even to credit-worthy customers, keeping loan-growth near levels last seen in the 1980s. Stressed corporates could derail the overall investment recovery for another two-to-three years, given they are using only 40 percent of capacity, according to India Ratings & Research, the local unit of Fitch Ratings.

In most economies, dampened demand, stagnant lending and slowing growth would push policy makers to announce a stimulus. Indian authorities don’t have much room to do so: inflation is accelerating as oil prices rise and the government already has Asia’s widest budget deficit.

Investments are unlikely to grow significantly in the year through March 2018, so private consumption will have to be the main driver of growth, according to analysts at Crisil Ltd., the local unit of S&P Global Ratings. Initial reports are encouraging: A private survey in September showed both manufacturing and services are recovering from the cash ban and the July 1 implementation of a goods and services tax. Hiring quickened.

Data such as car sales indicate an upturn and economic growth will pick up in October-March after slowing to a three-year low in the April-June quarter, central bank Governor Urjit Patel told the Mint newspaper in an interview published Monday.

“The Indian private sector regained some lost ground,” Aashna Dodhia, economist at IHS Markit, wrote in an Oct. 5 report.