Written by P R Sanjal and Rajesh Kumar Singh. This article first appeared in Bloomberg Technology.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has kicked off India’s race to turn all new passenger car sales electric by 2030. The largest order has gone to a company that hasn’t commercially started producing the vehicles.

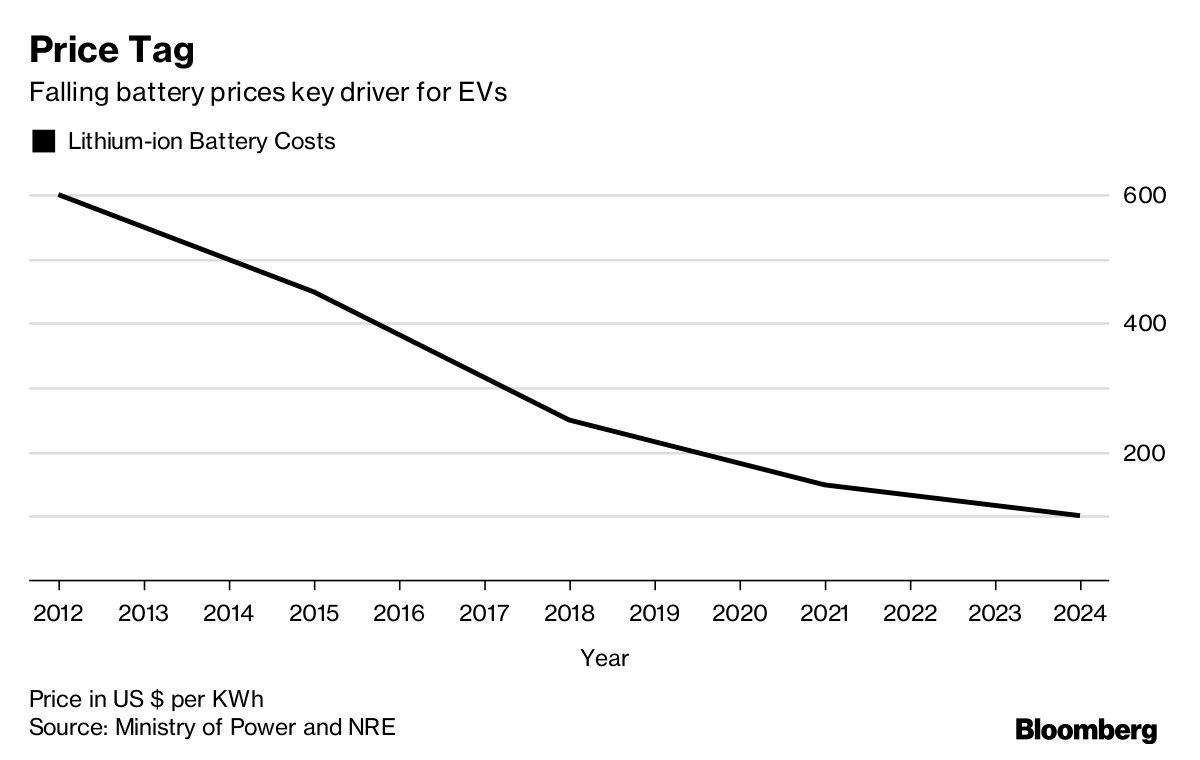

Tata Motors Ltd. hasn’t sold a single electric car yet, though Chief Executive Officer Guenter Butschek says its late-mover status is an advantage at a time when technology advances are leading to a fall in costs. Tata along with Mahindra and Mahindra Ltd. — India’s sole electric carmaker that plans to boost its vehicle manufacturing capacity to 5,000 units a month — underscore the distance to be covered when compared to China and the U.S.

Ramping up production of electric vehicles in a country where carmakers sell 2.5 million fossil fuel powered units annually is just one part of the problem, finding uninterrupted power supply is another. In addition, non-existent charging infrastructure further widens the gap between India and China, the current global leader. It had 336,000 new registrations in 2016, more than double of 160,000 in the U.S., while India had just 450 cars hitting the roads, according to the International Energy Agency.

“The government needs to set up charging infrastructure to make this electric business model sustainable,” said Ram Kidambi, partner at consultancy firm A.T. Kearney. “Indian automotive companies may be able to supply electric vehicles meeting the deadline. But the problem is what do the car owners do without the charging infrastructure?”

Falling Prices

The pursuit for all electric new car sales in less than a decade-and-a-half is part of Modi’s plan to champion the cause of combating climate change. Bloomberg New Energy Finance predicts the target will be “incredibly difficult” in the absence of a clearly defined policy and without subsidies. Chinese firms have benefited from generous funding offered by various regional governments.

India currently has about 350 charging points while China had about 215,000 installed at the end of 2016, according to the BNEF report. It will take about 15 years in India for total cost of ownership for electric vehicles to reach parity with conventional vehicles, around the time the south Asian nation plans to end sale of fossil fueled cars.

India’s EV target appears a little too ambitious, said Pawan Goenka, managing director at automaker Mahindra & Mahindra. “It would be little more moderate, though lot more aggressive growth path than what we have seen in other countries, but more moderate than being 100 percent electric vehicles by 2030.”

Modi’s administration is hoping to fast-track change by leading from the front. The government-backed Energy Efficiency Services Ltd. (EESL), which is tasked with helping the nation reduce emissions and curb fuel imports, is buying 10,000 battery-powered cars from Tata Motors and Mahindra & Mahindra to replace petrol and diesel cars used by the federal government in about four years.

Revenue Source

Electric vehicles open up a new source of revenue for India’s money-losing power retailers and could attract their enthusiasm in building the charging infrastructure, according to Shantanu Jaiswal, head of India research at Bloomberg New Energy Finance in New Delhi.

“In areas where the traffic volumes are high, it makes good business sense for distribution utilities,” Jaiswal said. “In rural areas though, where concentration of electric cars may not be very high, getting investments may still be a challenge, as we have seen in household electrification.”

Automobile ownership in India remains low, with only 18 cars per 1,000 citizens compared to nearly 69 in China and 786 for the U.S., a study by Niti Aayog, a policy planning body, and Colorado-based Rocky Mountain Institute. The scarcity of privately owned four-wheel vehicles and a large number of two-wheelers will enable Indians to leap frog into electric cars space as higher demand could lead to lower prices.

That’s what Tata and Mahindra are betting on. Tata is running trials of its electric buses after developing the plug-in versions of its Bolt and Tiago hatchback models. Mahindra has plans to expand its capacity to make electric vehicles almost 10-fold to 5,000 units a month in two to three years.

Tata Motors has a two part strategy — one which includes selling cars to the government– and then rolling out electric buses and trucks to cater to the mass transportation segment. Plans for both are ready, Tata’s Butschek said in an interview.

“We have invested a lot in electric vehicle business although we may not be outspoken about the same,” he said.