This article first appeared in Bloomberg Markets.

China’s President Xi Jinping said the world’s biggest producer and consumer of almost all commodities will deepen supply-side reforms and stick to the capacity cuts that have shaken up global raw materials markets.

China’s economy has shifted to a period where high quality is sought, moving away from its fast-growth era, Xi said during his opening remarks at the twice-a-decade National Congress of the Communist Party of China in Beijing. China will continue with its plan to deleverage and cut capacity, Xi said.

With few specifics on the capacity cuts provided by Xi so far, market reaction in China has been muted. Steel and aluminum futures in Shanghai were down 0.3 percent and 1.4 percent, respectively, as of 1:26 p.m. local time. Thermal coal futures were little changed in Zhengzhou, while state-run China Petroleum & Chemical Corp., the world’s biggest oil refiner, lost 0.5 percent in Hong Kong.

“I don’t think expectations were very high for specific details, but I also don’t think there was anything to suggest the government is changing tack on current strategy,” Daniel Hynes, senior commodity strategist at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd., said by phone from Sydney. “That includes things like capacity reductions and supply-side reforms, as well as infrastructure-led development. It does seem like status quo, which is broadly positive for commodities markets.”

The following is a breakdown of China’s capacity reductions up until now, based on government data, independent analysis and Bloomberg’s reporting, which may not be officially verified.

STEEL

China’s steel industry expanded from backwater to global giant in the past three decades and it’s now making the first concerted push to shrink the bloated sector.

Net capacity reductions — the amount shuttered minus new additions — will reach almost 200 million metric tons over 2016 and 2017, according to a Morgan Stanley estimate in a note dated Sept. 25, more than Japan’s total annual capacity. It still leaves China with a total capacity of about 1 billion tons a year.

- The first Five-Year Plan announced in January 2016 ordered 150 million tons of outdated or redundant official capacity to close by 2020, mostly in the state sector. More than 100 million tons have already been shuttered, according to government data.

- Mass closures of illegal and grey economy plants that employ low-tech induction furnaces, which were never counted in official steel output data.

- Orders for steel production to be temporarily reduced, with up to 50 percent of plants to close temporarily in the winter months across the steel hubs of northern China. This could theoretically lead to a loss of 32 million tons, according to Macquarie Group Ltd.

At the same time, the nation has been adding fresh, mostly low-cost capacity, which consultant Kallanish Commodities Ltd. estimates at 5.8 million tons last year and as much as 30 million tons this year.

Increased supply after the temporary closures in winter “should eventually overwhelm demand, restoring inventories and bringing down steel prices with it,” Macquarie analysts said in an emailed note dated Oct. 10. “As Chinese domestic prices turn lower, steel exports will rise, eventually putting downside pressure on other regions, including the U.S.”

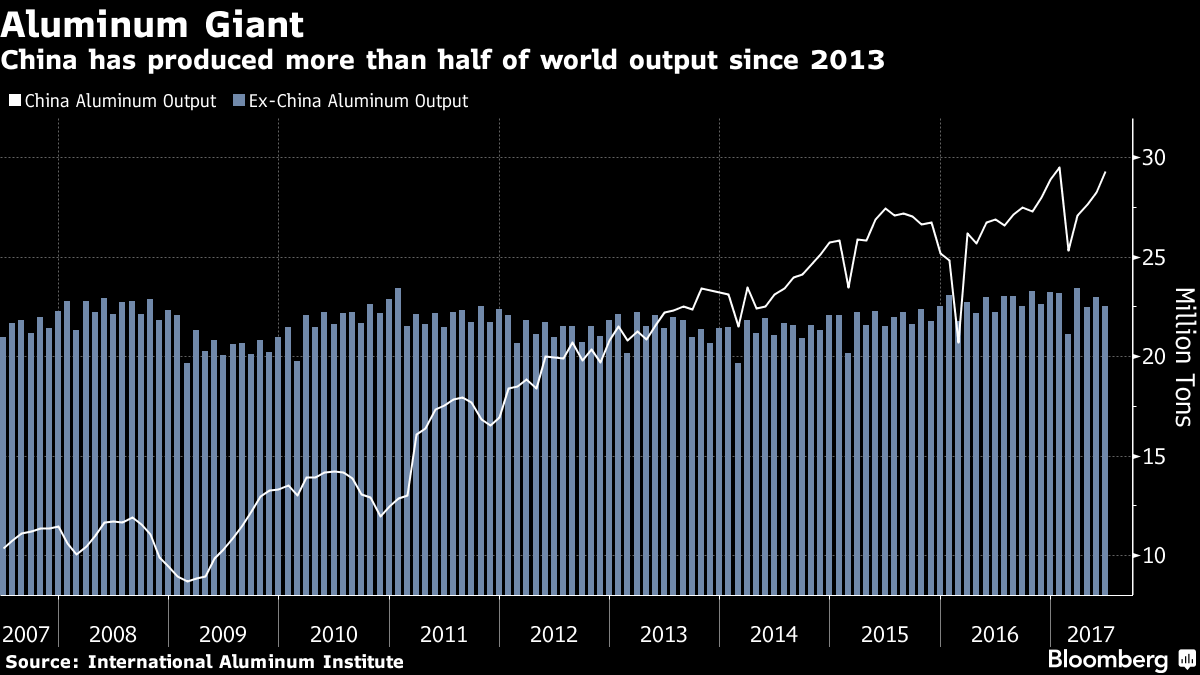

ALUMINUM

The combination of shuttering of unlicensed capacity, stricter environmental controls and winter curbs have put a rocket under aluminum prices. Some 4 million tons of unapproved primary aluminum smelters have been shut down across China, according to Citigroup Inc. Winter controls could mean as much as one million tons in lost output.

“There’s still 8.5 million tons of new capacity coming on stream up to 2020, and then you have the plants that have already shut down that could well come back at some point,” Paul Adkins, managing director of consultant AZ China Ltd., said in an interview. “Given the political environment though, certainly nothing is going to restart any time before spring next year.”

COAL

The initial goal set in 2016 to eliminate 500 million tons of annual coal capacity by 2020 was later raised to 800 million. Regulators also said they wanted to add 500 million tons of newer, more-efficient capacity, which was also later boosted to about 800 million tons, implying almost no net change, according to Laban Yu, head of Asia oil and gas equities at Jefferies Group LLC in Hong Kong.

The government started by closing high-cost, money-losing mines while limiting output from all miners, including efficient low-cost producers, to help the over-leveraged industry and avoid instability in some coal-reliant provinces, such as Shanxi, according Yu.

Cuts this year will amount to 190 million tons while new advanced capacity will increase by 300 million tons, according to Jefferies. Between 2015 and 2020, the brokerage estimates a reductions of 875 million tons against new capacity additions of 750 million tons. While overcapacity may be trimmed, it will still be a problem by the end of 2020, and cuts this year won’t be as easily achieved as they were previously, Michelle Leung, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, wrote in a report on Oct. 17.

“The supply reform program has not only achieved a temporary production reduction in 2016, but has also brought long-lasting structural supply discipline with higher environmental and safety requirements,” HSBC Holdings Plc analysts including Jeff Yuan wrote in a report this month. “China and seaborne market supply-demand will be tighter for longer, which helps to support prices both near and long term.”

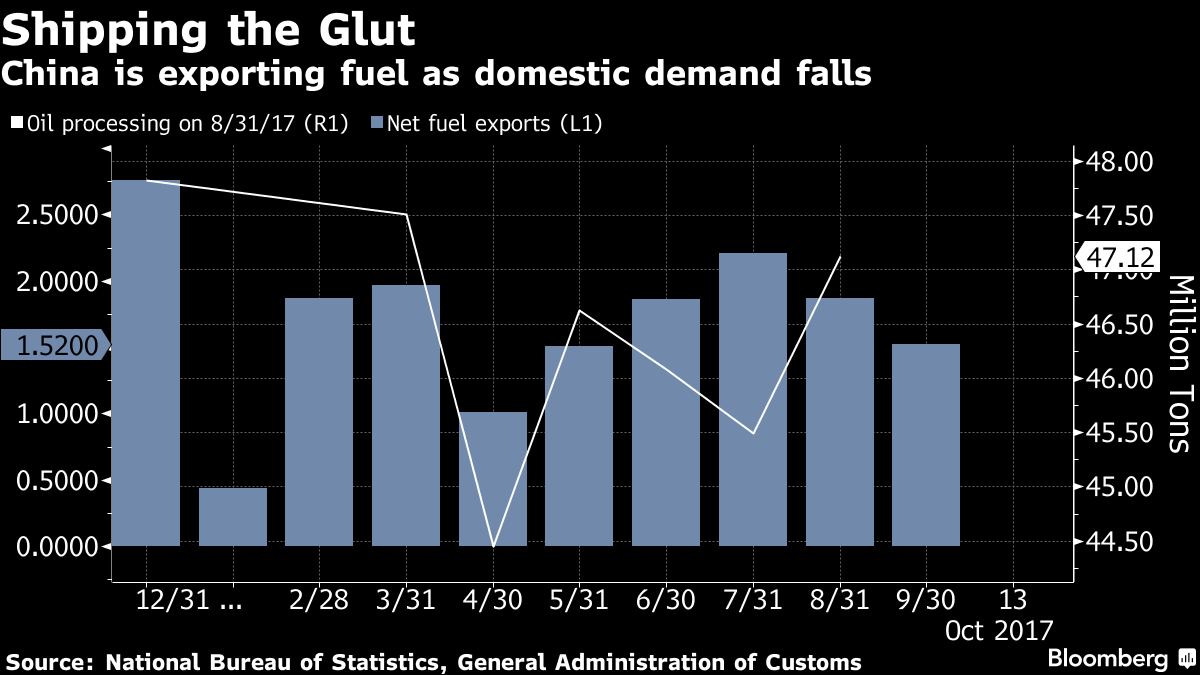

OIL REFINING

While China’s drive to curb overcapacity has so far left its oil refineries unscathed, the industry may be primed for reform. Fuel makers are being squeezed by competition from alternative fuels as the nation tries to protect its environment, and signs of slowing demand growth.

The nation’s refiners face “severe overcapacity” and must both cut costs and carefully gauge expansions and upgrades so that fuel production matches demand, according to China’s biggest oil producer, China National Petroleum Corp.

Refineries are already capping operating rates at levels lower than the global average. CNPC estimates only about 557 million tons of the nation’s total processing capacity of 790 million tons will be used in 2017, leaving about 30 percent of its refining facilities idle.

AGRICULTURE

China’s government-backed environmental clean-up has even spilled over to the meat industry. China closed down or relocated over 200,000 pig and chicken farms in the first half of the year as part of a plan to tackle water pollution, according to the Ministry of Environmental Protection.