The future of Germany’s coal industry is moving back into the spotlight as Chancellor Angela Merkel restarts talks on forming a new coalition government, with pressure building for stricter limits on the most polluting fuels.

Two months after national elections, discussions aimed at forging a novel four-party government collapsed at the weekend in Berlin. While that breakdown provided a respite for shares of coal burning utilities including RWE AG and Uniper SE, the issues of carbon dioxide emissions and climate policy loom large with coalition talks set to begin again.

“Whatever emerges as the next government, at least a minimum consensus on cutting coal” should be expected, “and looks likely to stick,” said Claudia Kemfert, who heads Berlin’s DIW institute’s energy desk, on the phone Friday. Kemfert advises the government on energy policy in an independent capacity and is an exponent of a quicker coal exit.

Coal power catapulted to the center of coalition wrangling in recent weeks after signs emerged that Germany’s falling further behind in cutting emissions. That in turn prompted calls to assuage Germany’s international allies that the country is serious about meeting its commitments. A working consensus emerged among the coalition hopefuls to cut emissions, according to participants from the three of the four parties.

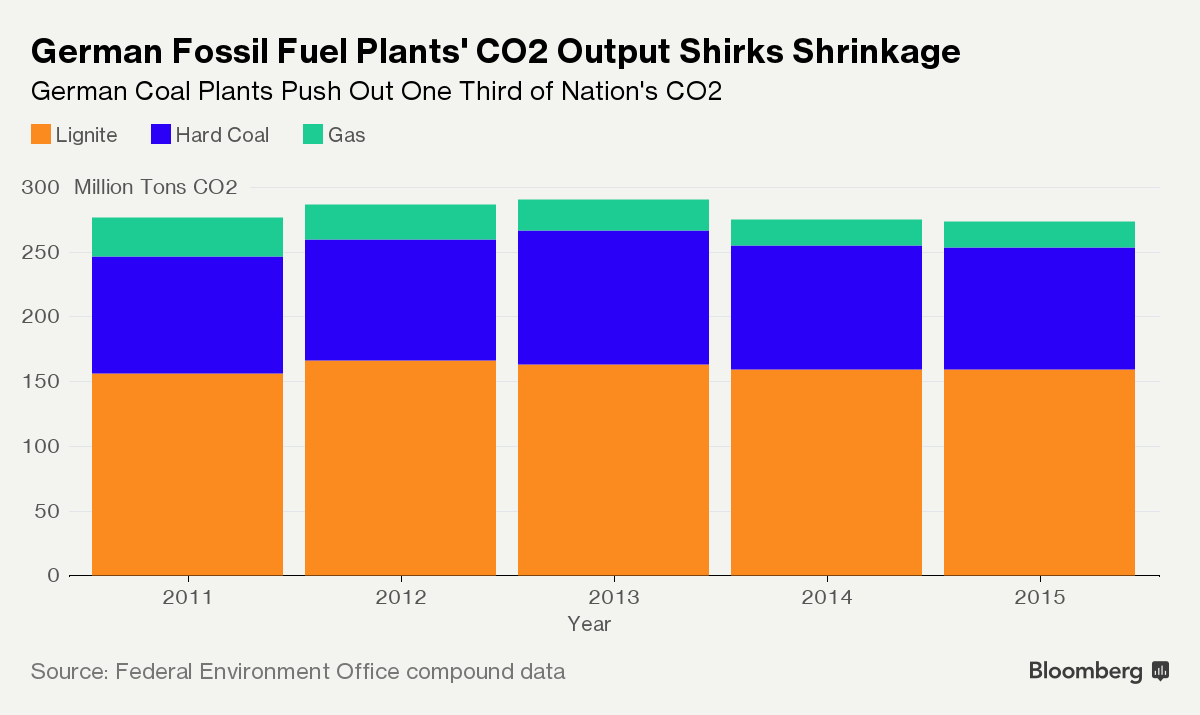

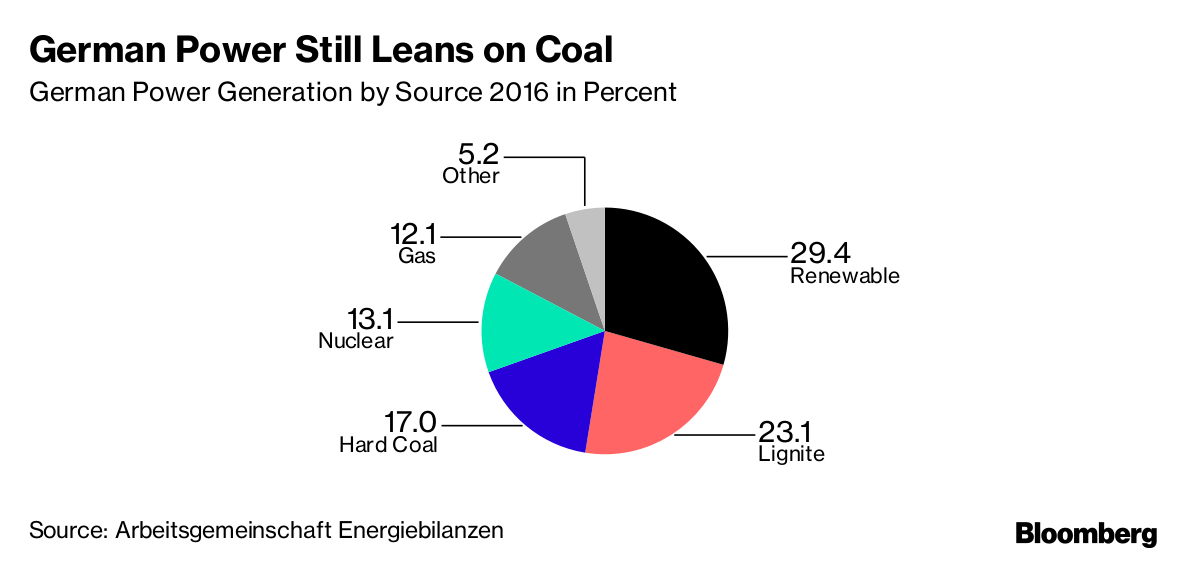

Coal power supplied about 40 percent of all Germany’s electricity last year but about a third of its carbon dioxide pollution. That underscores the dilemma of balancing energy security and climate protection. Germany currently has more power generation it needs to feed demand.

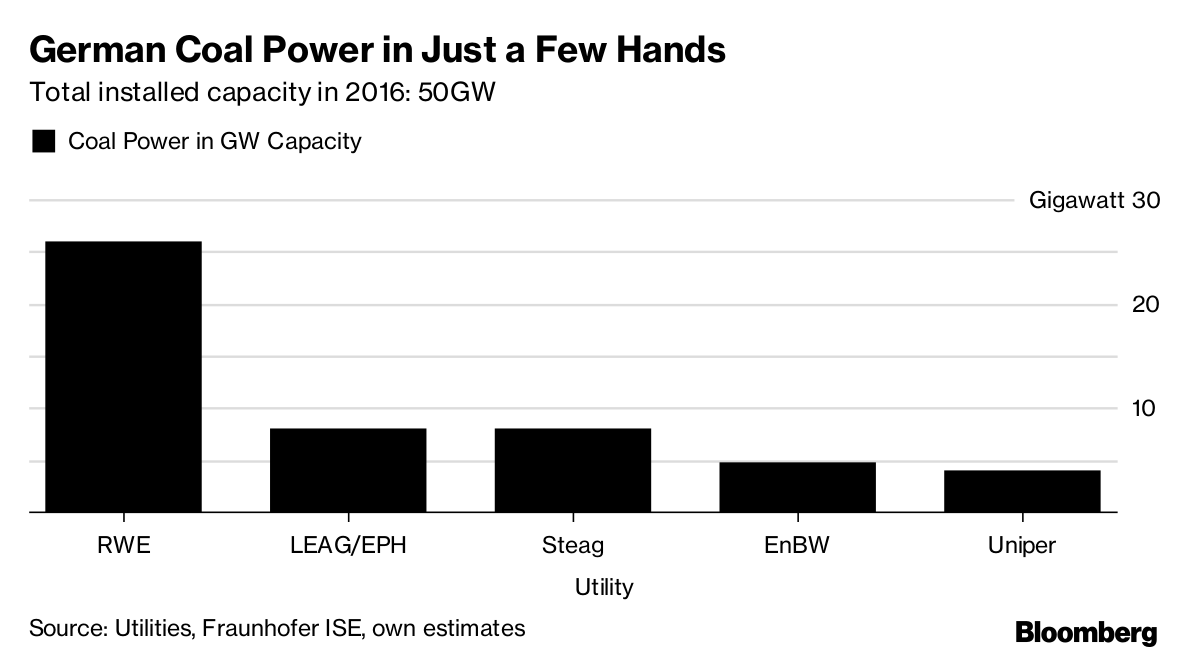

Essen-based Steag GmbH applied to shut six coal plants last year, leaving it with eight working units after plummeting wholesale prices made them unprofitable. Power prices have recovered this year, helping lift the sales and shares of utilities that operate them including Uniper and RWE.

Coal power in Germany is highly concentrated and bundled mainly in the hands of five industry champions. RWE, the nation’s biggest electricity generator, has combined lignite-hard coal assets of about 26 gigawatts, an eighth of all installed power in Germany. The relatively modest generation curbs, along with the prospect for compensation may ease the plan’s acceptance by operators, according to the participants.

Capping coal power to reach the carbon dioxide target gained tentative support from the power industry’s BDEW lobby, which wrote Nov. 16 in Die Welt newspaper that a 5-gigawatt power cap was justifiable because lignite plants weren’t the sole target of closures and that those who operate the plants will have to be compensated for closing them.

Just how much the state will pay for compensation is likely to be a sticking point for the parties in coalition talks when they return to the table.