BHP Billiton Ltd., the world’s biggest mining company, said wider use of systems that trap carbon emissions will be needed to meet international climate goals, even as investments in the technology stall.

“We have knowledge of geology, markets and economics, so there’s probably something we can bring to the table here in terms of our understanding around CCS to try to push this technology down the cost curve so it can be more readily available at scale and affordable costs,” Fiona Wild, a BHP vice president for sustainability and climate change, said in an interview.

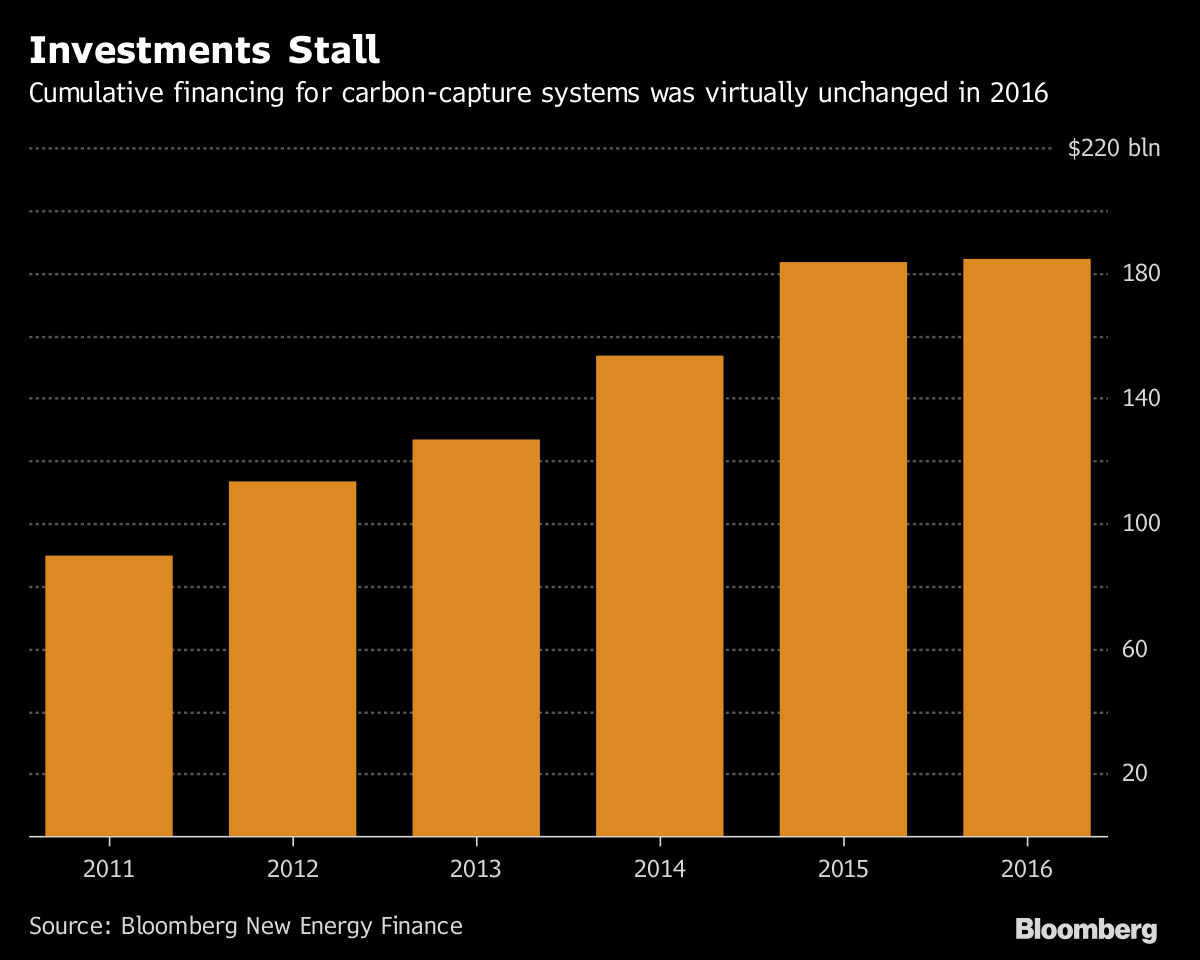

Cumulative investment in carbon-capture and storage worldwide was virtually unchanged at $184.4 billion in 2016 compared with the previous year, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. To meet the Paris accord’s climate targets, more than 2,000 such facilities will be needed by 2040, and they must account for 14 percent of cumulative emissions reductions, the Global CCS Institute has said. Just 17 large-scale facilities operate globally now, with four more starting operations next year, according to the Institute.

BHP, which mines metals and coal, started a collaboration in 2016 with Peking University that might lead to a pilot carbon-capture project with a steel company in China, Wild said.

In contrast to power generation, where it’s possible to shift from coal or gas to renewables, industrial activities like steel making and cement manufacturing don’t have good options for lowering emissions, so carbon-capture systems have “a really strong role to play in steel,” she said.

Zero Emissions

BHP’s plans are part of a larger push by the company to achieve net-zero operational greenhouse gas emissions in the second half of the century. In the nearer term, BHP’s goal is to keep emissions by 2022 at or below 2017 levels.

Carbon capture and storage systems are a key component of BHP’s strategy because they “have the capability to materially reduce global emissions” across many industries, Wild said.

Carbon capture and storage systems separate carbon dioxide from other emissions generated when coal, oil or natural gas is burned. It can then be injected into geological systems underground in a liquefied state.

“People will continue to use fossil fuels for quite a number of decades, and without CCS I don’t know how we will reach climate goals,” Wild said.

Canada Center

BHP’s partnership with Peking University is aimed at understanding what technical and economic barriers are blocking deployment of carbon-capture systems in the steel sector, and trying to develop policies and a road map to overcome them, she said.

BHP is also cooperating with Canadian energy company SaskPower International Inc. on a carbon-capture knowledge center in Canada to learn from the world’s first commercial-scale plant that burns coal while cutting carbon emissions by 90 percent. And the company in April started a research project with the University of Melbourne, the University of Cambridge and Stanford University to examine long-term storage of carbon dioxide.

Deploying the technology at the scale needed will require policy and regulatory support, as well as broader societal acceptance, Wild said.

“It’s hard at the moment to make CCS sexy,” she said. “But as time goes on, I think CCS becomes a really important part of the mitigation response to climate change.”