Soon after it began in 2011, South Africa’s renewable power program became the world’s fastest-growing.

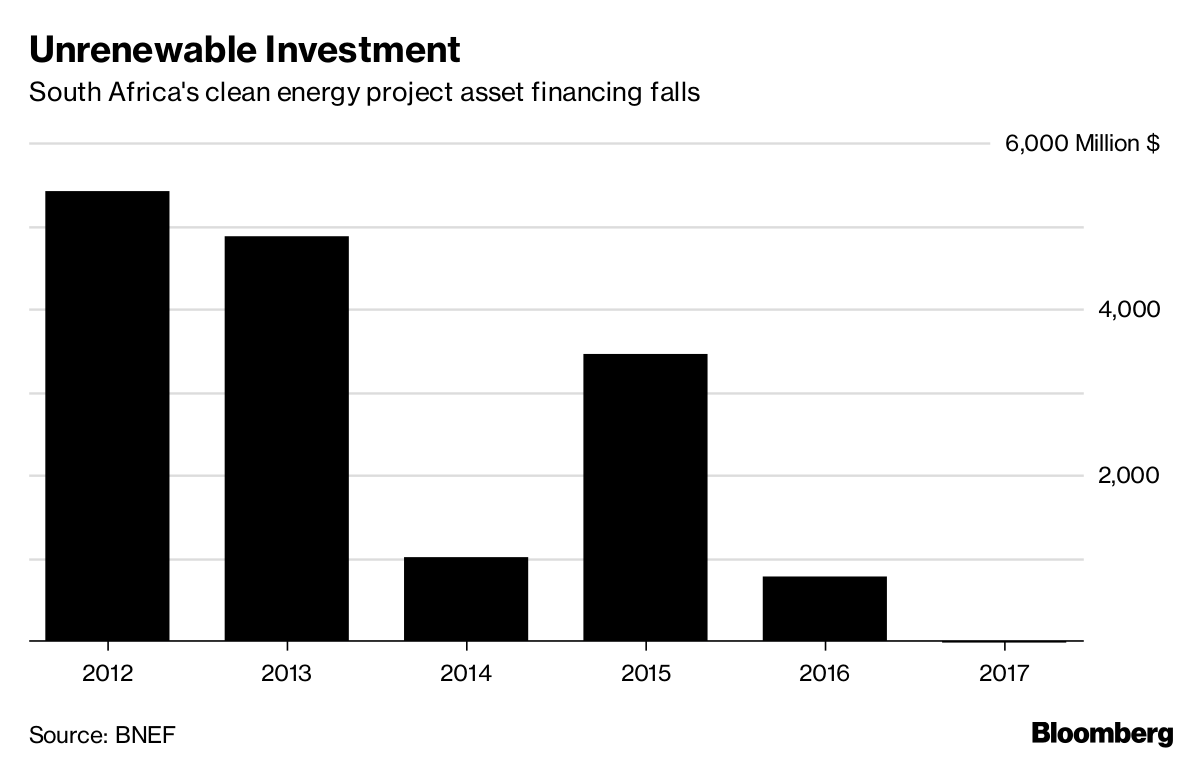

Almost $15 billion poured into clean energy in seven years, financing everything from wind farms to solar towers. New independent power producers mushroomed, signing electricity-purchase agreements with national utility Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd that were guaranteed by the government.

Brian Molefe. Photographer: Waldo Swiegers

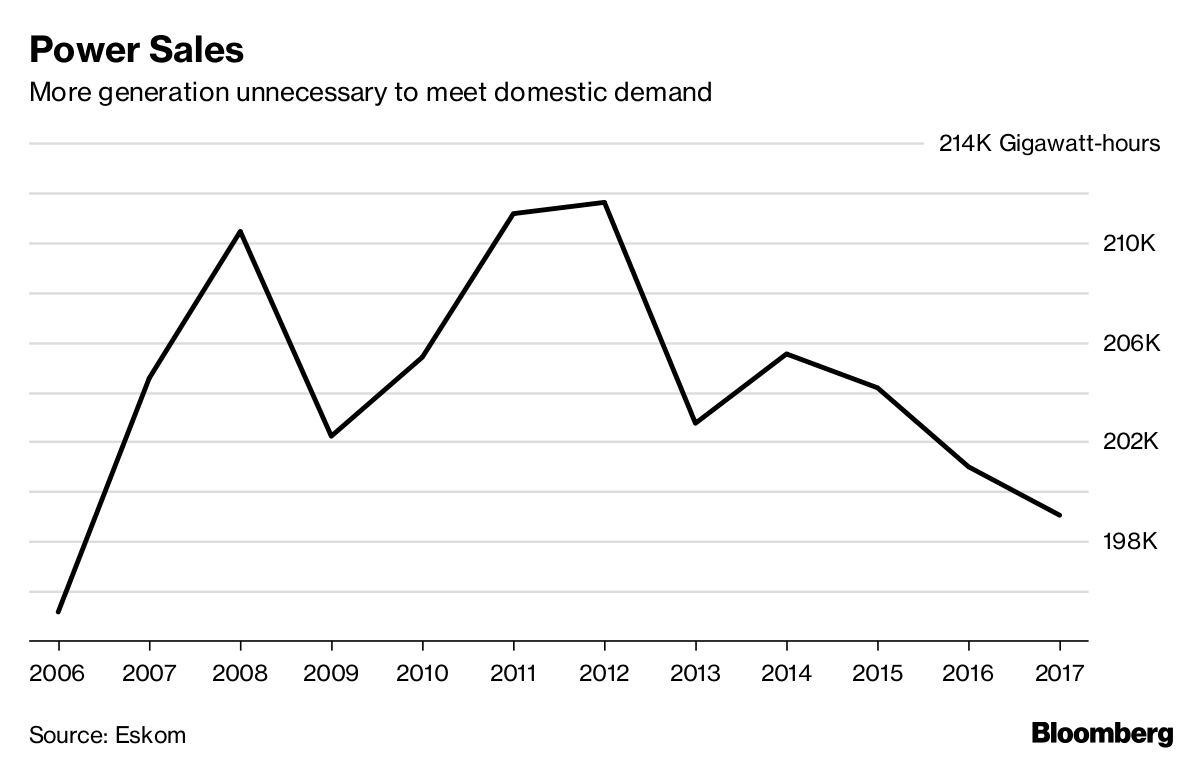

Then Brian Molefe, whom a subsequent graft probe would show was closely connected to President Jacob Zuma, became Eskom’s chief executive officer in 2015. He stopped signing new contracts, saying the country didn’t need more renewable production because it was too expensive. At the same time, power demand lagged as companies generated their own and the economy slowed. And Eskom was put in charge of an expensive nuclear-construction program championed by Zuma.

As a result, renewable financing dropped to a trickle of $4 million last year, with more than two dozen projects that were near the point of breaking ground still waiting. The freeze-out risks driving away badly needed investors – many of whom are now expanding elsewhere.

“Eskom and the South African government have done potentially unrepairable damage to one of the most effective renewables auction programs in the world,” said Victoria Cuming, head of policy analysis in Europe, the Middle East and Africa at Bloomberg New Energy Finance. “Even if the government proceeds with the auction scheme, political and policy risk will be much higher, increasing project costs and making it harder to secure financing.”

It’s a painful example of the economic erosion occurring under Zuma. Graft and mismanagement of state-owned companies have scared off investors, and the country had its second recession in less than a decade earlier last year. Zuma himself is alleged to have taken more than $300,000 in bribes from arms dealers and is trying to persuade prosecutors to drop charges of corruption, racketeering, fraud, and money laundering. After some back-and-forth, Molefe was pushed out in 2017.

Pylons sit beyond photovoltaic panels in Kathu, South Africa. Photographer: Waldo Swiegers

Cyril Ramaphosa, who assumed leadership of the ruling party last month – and thus became Zuma’s probable successor – has started making efforts to reverse the damage. He called in November for an expansion of renewable energy to reduce carbon and create jobs, saying “we could again become the investment destination of choice for activities that are electricity intensive.”

At present, investors are left with little more than hope. The Energy Department will make an announcement on the renewable contracts “once the decision is made,” spokeswoman Nomvula Khalo said in an emailed response to questions.

While the role of renewables is still likely to grow in South Africa, delays “have put significant pressure on developers who have invested a great deal in development costs to date,” said Nandu Bhula, deputy managing director for Southern Africa at Saudi Arabia’s ACWA Power International, which is seeking to develop its second solar program in the country. “With all financing and technical contracts requiring renegotiation to remain valid, these costs continue to increase.”

At the time the renewable program began, the national power grid was dealing with a shortage of capacity and overdue maintenance on its coal plants, which in 2015 resulted in sustained electricity cuts. The clean energy projects could be installed quickly, compared to the mammoth coal facilities the country had been building, usually both late and over budget by billions of dollars. The auction program was accelerated, with extra rounds added to bring more power generation as soon as possible.

But just a year later, enough coal-fired capacity had been added to the grid to end the blackouts, especially amid weak demand. Eskom had surplus power generation capacity. In media interviews, Molefe questioned the cost and reliability of renewables, and he started promoting nuclear power as a better alternative.

The loss of confidence in the program has been exacerbated by a revolving door in the energy ministry, said Siyabonga Mbanjwa, regional managing director of SENER Southern Africa, an EPC contractor for renewable projects. A succession of energy ministers – David Mahlobo was the third person to serve in the role last year – promised that the agreements with independent power producers would be signed, and failed. Zuma, in his annual state-of-the-nation speech in February 2017, also said the deals would be completed. There’s been no result.

“We have moved from having one of the most successful renewable-energy IPP procurement programs in the world to a deadlock that has resulted in job losses,” Mbanjwa said in an interview.

Electricity power lines at Eskom Holdings Ltd.’s Kendal power station in Delmas. Photographer: Nadine Hutton

SMA Solar Technology AG closed its South African operations. Another plant that made wind turbines shut down. International firms such as ACWA and Enel SpA have maintained efforts to build their portfolios elsewhere, bidding for renewables deals throughout the continent in nations including Morocco and Ethiopia.

Energy policy must be consistent to make it attractive to foreign investors, Jasandra Nyker, CEO of developer BioTherm Energy, said at a government-organized energy conference last month. “When we have ‘stop-start’ strategies it kills the local supply chain,” she said.

New leadership could help revive the program, according to Anton Eberhard, professor at the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business. Ramaphosa “is likely to stop the nuclear procurement and restart the renewables program, although probably at a reduced scale,” he said.