The secret to switching the global energy system entirely to renewables may lay in the universe’s most abundant substance.

Hydrogen has drawn backing from big energy companies from Royal Dutch Shell Plc to Uniper SE in addition to carmakers BMW AG and Audi AG. They’re supporting research into how the element can be used to store energy for weeks or even months beyond what lithium-ion batteries can manage.

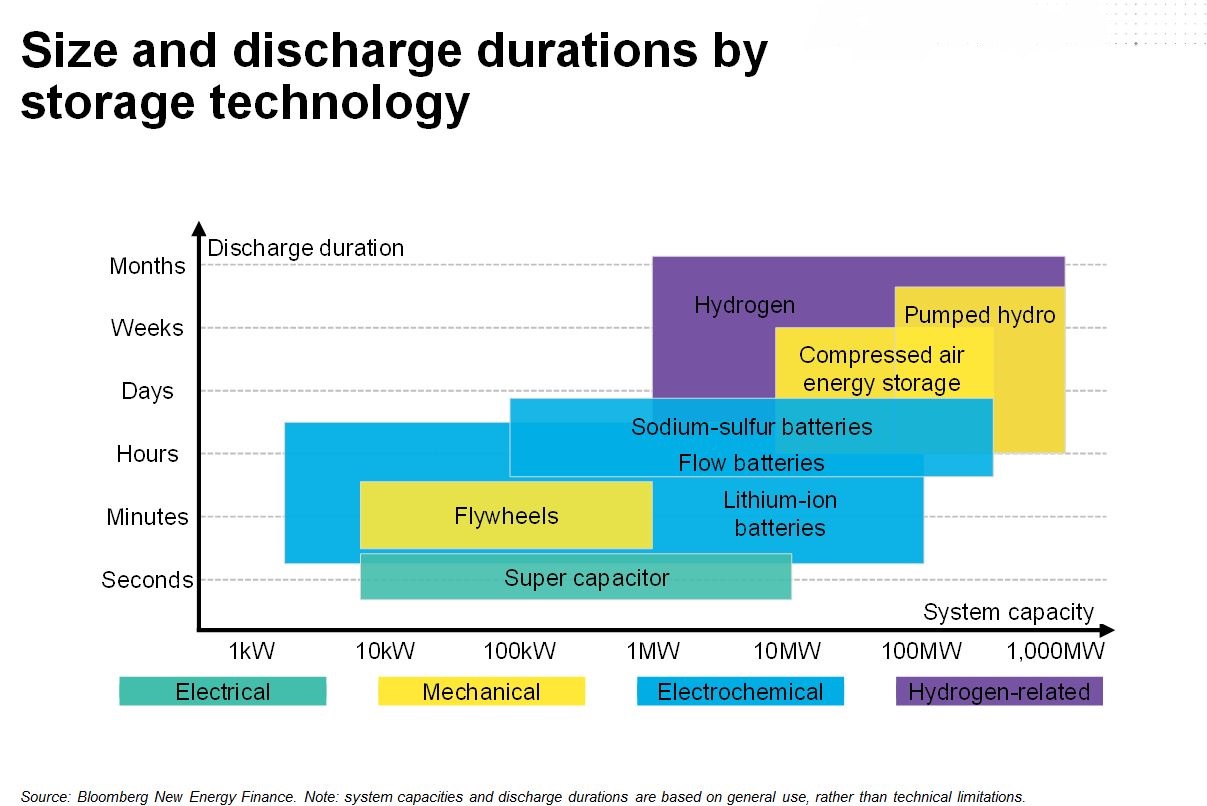

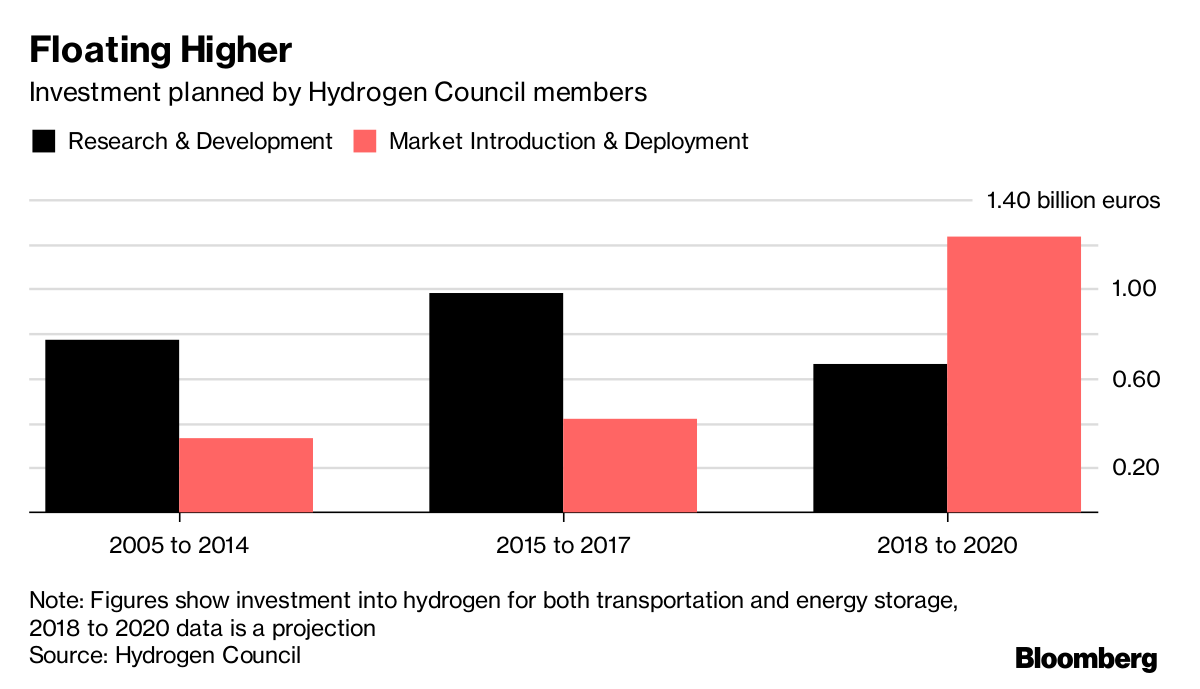

While industry’s investment in hydrogen is small at just $2.5 billion over the last decade, the work offers an answer to the elusive question of how electricity could be kept for use in the future. Batteries increasingly are shifting power from day to night, but they tend to go flat after a few weeks. Hydrogen can be kept indefinitely in tanks. That would allow, for example, voltage collected from solar panels in the summer to be used in winter.

“The years 2020 to 2030 will be for hydrogen what the 1990s were for solar and wind,” said Pierre-Etienne Franc and vice president of advanced business and technologies at the French industrial gas maker Air Liquide SA and initiative secretary of the Hydrogen Council, a trade group promoting the work. “It’s a real strategic shift.”

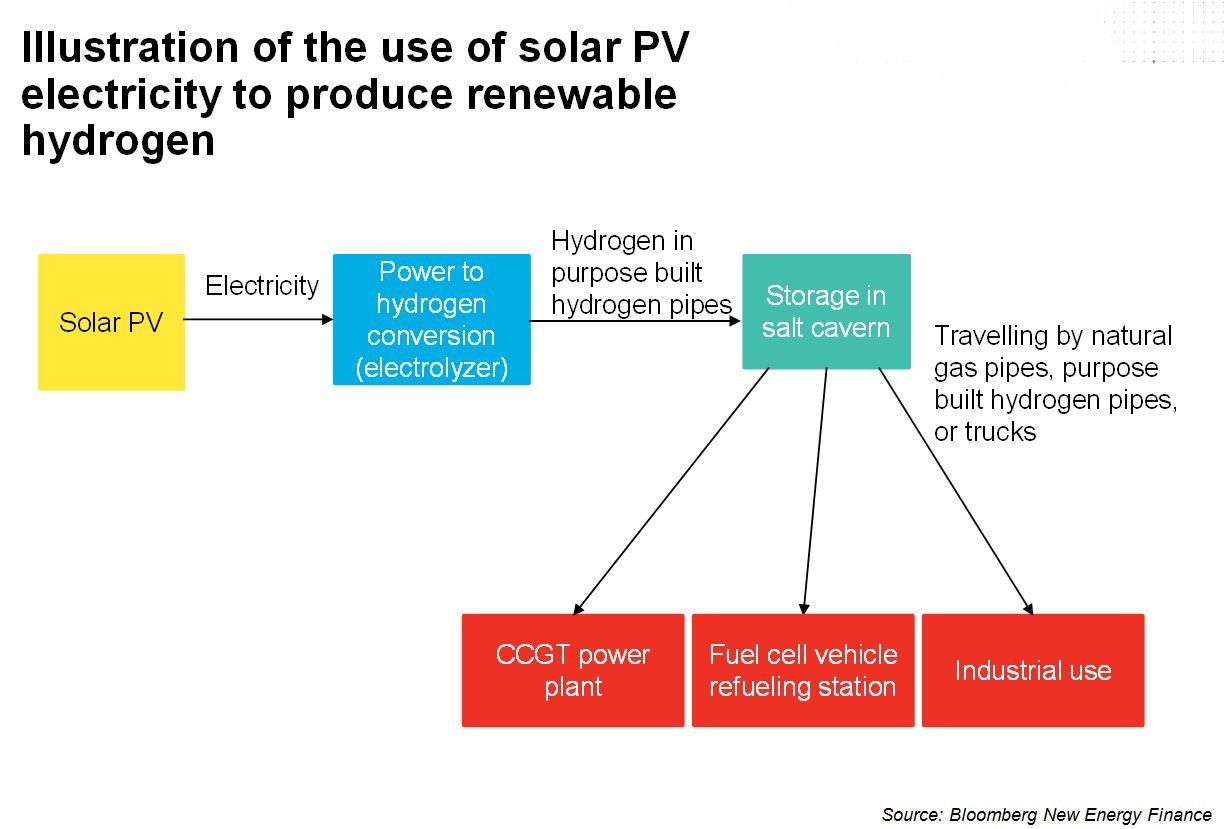

Excess power from wind or photovoltaics would drive electrolysis, separating water into its component hydrogen and oxygen elements. The hydrogen captured by that process could, whenever needed, feed natural gas power plants or fuel cells to make electricity. Industrial plants like oil refineries can also use hydrogen for chemical processes.

To date, the energy industry has focused mainly on hydrogen’s potential in fuel cells, which use the element in a chemical reaction to generate electricity. On power-storage, most of the money is going into batteries like the lithium-ion cells widely used in mobile phones and laptop computers. But those tend to lose charge if not topped up and discharged frequently.

Hydrogen storage is attractive because it preserves energy for longer periods. The only real alternative at the moment is pumping water onto a hilltop reservoir, where it can dammed up until grid managers are ready to let it flow down through hydropower turbines. That so-called pumped storage requires the right geography.

“If you want to get to 100 percent renewables, hydrogen could play a key role,” said Claire Curry, an analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance. “You could have natural gas plants, but that would, of course, not be 100 percent clean.”

The work on hydrogen is in its infancy, but support with big business is growing. The Hydrogen Council was formed at the last World Economic Forum in Davos, with 17 major companies looking for ways to integrate the gas into cleaner energy systems. Its members include Shell, Total SA, Engie SA, Toyota Motor Corp., Bayerische Motoren Werke AG, Audi and the Japanese industrial gas supplier Iwatani Corp. General Motors Co. is in the process of joining.

Curry’s research at BNEF suggests a hydrogen storage system could work in an area like West Texas, where there’s abundant existing energy networks and customers to support transforming solar into the gas. She evaluated a theoretical 1 gigawatt solar farm feeding a unit that makes hydrogen and found that in the right circumstances a hydrogen storage unit could be profitable.

For a BNEF research note on how hydrogen storage can pay, click here.

Hydrogen has drawbacks. Government incentives are required to create a market for storage capacity, Curry said. And for now, batteries are the alternative for many of the functions hydrogen would fulfill.

The whole idea of converting power into a gas and then back into power strikes some as convoluted. Erik Fairbairn, chief executive officer of Pod Point Ltd., an electric-car charging network in the U.K., believes that hydrogen’s role should be limited to allow more simple technologies to flourish, particularly when a battery could do the job.

“Generally speaking when you change energy from one form to another, you lose efficiency,” Fairbairn said. “You create hydrogen mainly by electrolyzing water, using electricity to split the hydrogen from oxygen and right off the bat, you lose a quarter of your energy to this.”

Still, the companies involved are optimistic about the technology and are prodding governments to back it.

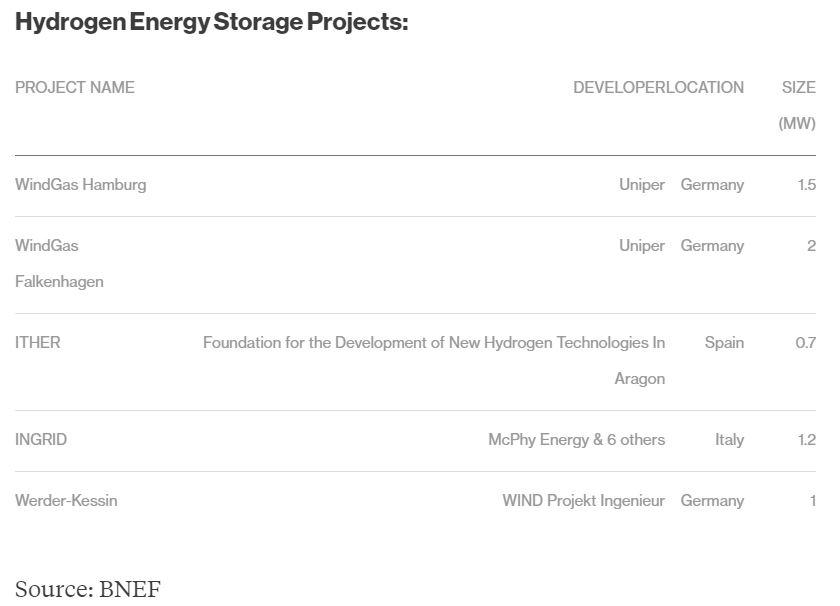

For a list of hydrogen storage projects and their promoters, click here.

The electronics maker Toshiba Corp. and utility Tohoku Electric Power Co. are also working on a hydrogen project in Fukushima, Japan. The plant will be 10 megawatts and is due to begin operations in 2021. It may be the world’s largest once it is complete.

Uniper started its Falkenhagen plant in August 2013 to converts excess wind power into hydrogen, which is fed into a plant that combines it with carbon dioxide to make methane — natural gas. That gas is transported and stored in the existing pipelines.

“Power to gas is a key technology,” said Eckhardt Ruemmler, a board member at Uniper responsible for innovation. “The use on a large technical scale is currently impeded by insufficient political framework.”