Written by Joe Ryan and Jim Polson. This article first appeared in Bloomberg Markets.

The key to replacing aging nuclear plants in the U.S. Northeast may lie 1,000 miles away, along a remote river tumbling through the Canadian wilderness.

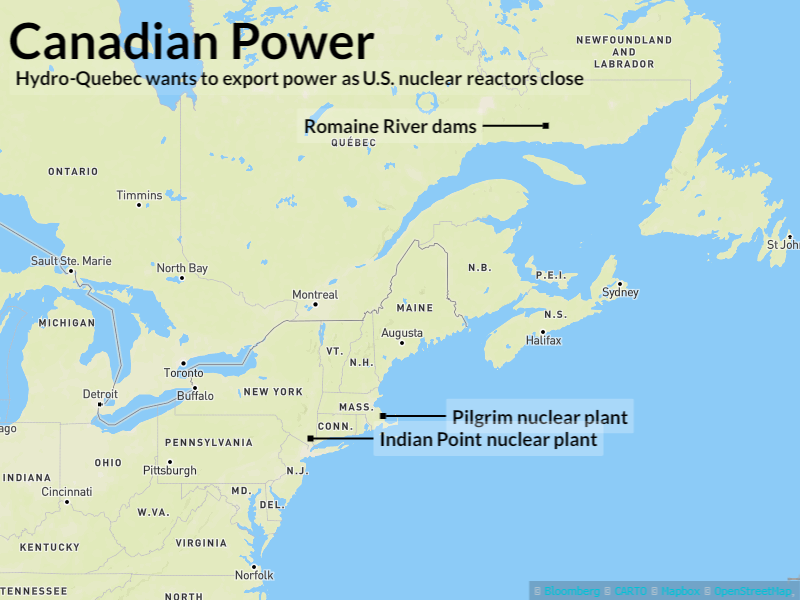

In boreal forests above the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Hydro-Quebec is building a series of dams that will generate enough electricity for more than one million homes. The $5.2 billion project on the Romaine River is part of a sweeping expansion the government-owned utility began in 2007, with the intention of selling power to the U.S. where nuclear reactors are closing.

It’s not clear Americans will buy. While New York and Massachusetts want to avoid fossil fuels when they replace the soon-to-be-shuttered Indian Point and Pilgrim nuclear plants, wind and solar developers are also jockeying for the job. That’s left Hydro-Quebec, Emera Inc., Nalcor Energy and other Canadian generators promoting the idea that hydroelectric power is cheap, dependable and — despite what environmentalists assert– clean.

“If people decide to let nuclear go, and they still want to be zero carbon — there are not a lot of options besides hydro,” Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard said in an interview at Bloomberg’s headquarters in New York. “You can supplement your needs with wind and solar, but you absolutely need a stable and reliable baseload.”

Hydro-Quebec, Canada’s largest hydroelectric generator, has plenty at stake. It’s pledged to double revenue by 2030, even as demand within the province stagnates. That makes exports crucial. The utility has proposals pending with New York and Massachusetts to deliver as much as 2.2 gigawatts, through state-run clean energy auctions that also drew bids from scores of wind and solar companies.

“Hydro-Quebec has to find a way to increase profits,” said Normand Mousseau, a University of Montreal professor who co-authored a 2014 government study on the province’s energy market. “Since demand in Quebec is not going up, they have to sell.”

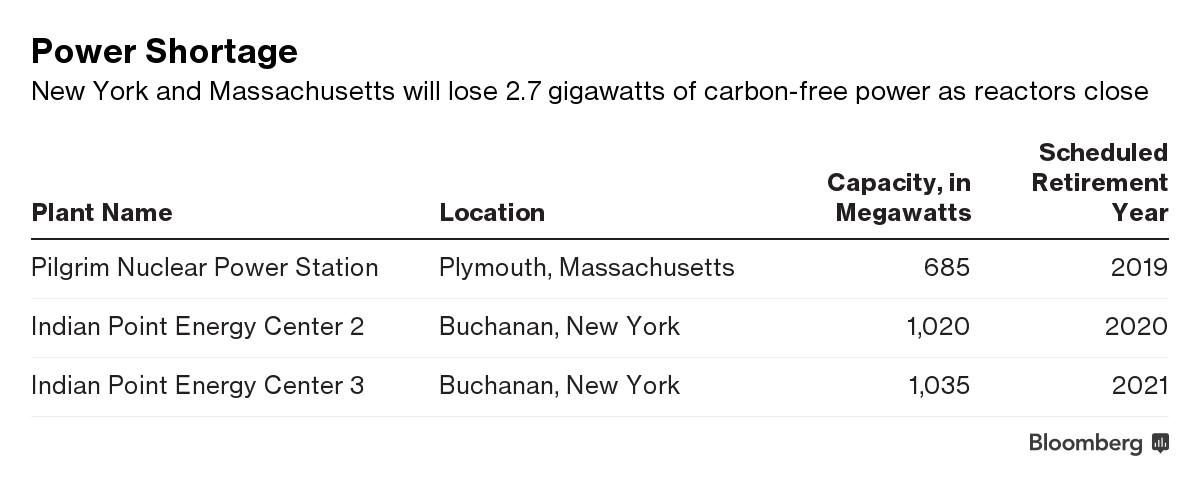

The stakes are also high in Massachusetts and New York, which have ambitious goals to fight climate change. When Entergy Corp. closes the Pilgrim nuclear plant near Boston in 2019, the state will lose 685 megawatts of carbon-free electricity. New York stands to lose more than 2 gigawatts when Indian Point’s two reactors close in 2020 and 2021.

Transmission Options

“We would ideally like to see wind and solar replace Indian Point,” said Robert Freudenberg, a vice president for energy and environment at the Regional Plan Association, an urban research and advocacy group. “But we’re not naive enough to think that we can get there that quickly.”

Hydro-Quebec already sends about 24 million megawatt-hours of electricity to the U.S. annually, the utility’s Chief Executive Officer Eric Martel said in an interview. Exporting more would require more transmission capacity in the U.S. It’s partnered with three developers pushing to build power lines, including two fully permitted projects proposed by Transmission Developers Inc., a Blackstone Group LP company.

Hydro-Quebec’s Romaine River-3 dam is scheduled to be complete this year.

“Canadian hydro is massively destructive,” while homegrown renewables can replace nuclear reactors and are better for the environment, said Mark Kresowik, eastern region deputy director of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign.

Hydro-Quebec rejected the notion that its dams cause widespread environmental damage. Spokeswoman Lynn St-Laurent said northern temperatures minimize carbon emissions and hydro is among the cleanest ways to generate electricity.

Massachusetts’s clean energy auction received more than 40 bids from companies other than Hydro-Quebec, including NextEra Energy Inc.’s solar development arm and the offshore wind developer Deepwater Wind LLC. The state will announce winners next year. New York received more than 200 proposals for auctions to meet a state goal of sourcing 50 percent of its power from clean sources by 2030, and will announce winners in November.

“Our hydroelectricity is competitive,” Quebec Finance Minister Carlos Leitao said in an interview. “If, despite these arguments contracts don’t get signed, we don’t depend on them — we’ll do something else.”