Written by Thomas Wilson and Thomas Biesheuvel. This article first appeared in Bloomberg Markets.

For evidence of just how hot battery ingredient lithium is right now, look no further than Australia’s AVZ Minerals Ltd.

A penny stock until a few months ago, the mining hopeful has surged about 1,500 percent this year. The proposition: recasting a remote, century-old tin mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo as a supplier of lithium needed to power electric cars.

While its rise has been dramatic, AVZ isn’t alone in the rush to position for a rechargeable-battery boom. In the U.K., a company founded by former investment banker Jeremy Wrathall is planning to tap thermal springs in Cornwall, a region more famous for its beach coves. Other companies are hunting for lithium deposits from Germany to Mali, and even Afghanistan plans to tender exploration permits.

“You’ve got a scramble for deposits, a demand side that looks very impressive, the question is always around the supply,” said Paul Gait, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein Ltd. in London. In the rush to meet demand there is a risk too many mines will be developed and too much metal supplied, Gait said. “When the tide goes out, those that do not have good geology will always be found wanting.”

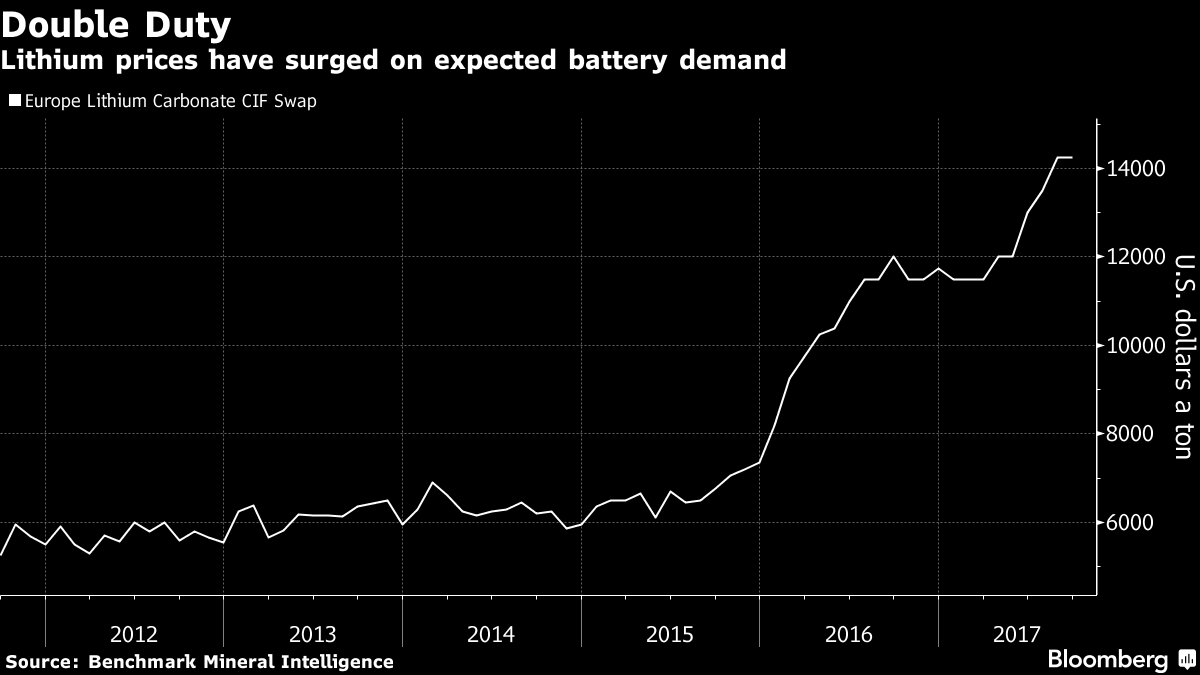

Lithium, which is dominated by three large producers, has surged as demand increases for lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles and energy-storage systems. Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects that electric vehicles will make up more than half of new sales globally by 2040. And uncertainty about global production growth means car manufacturers are seeking to lock-in future supplies of the metal.

Yet while production might struggle at first to catch up with demand growth, lithium isn’t really rare compared with other battery metals like cobalt and graphite, according to Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Eily Ong. And mining history is full of cautionary examples of booms that ended in bust when the rush to boost supply overshot demand growth.

Iron ore is a recent example, after a boom in Chinese steel production led to a push to build new mines. That turned out poorly for many of the iron ore upstarts that either struggled to build projects or brought mines into production just in time for prices to drop.

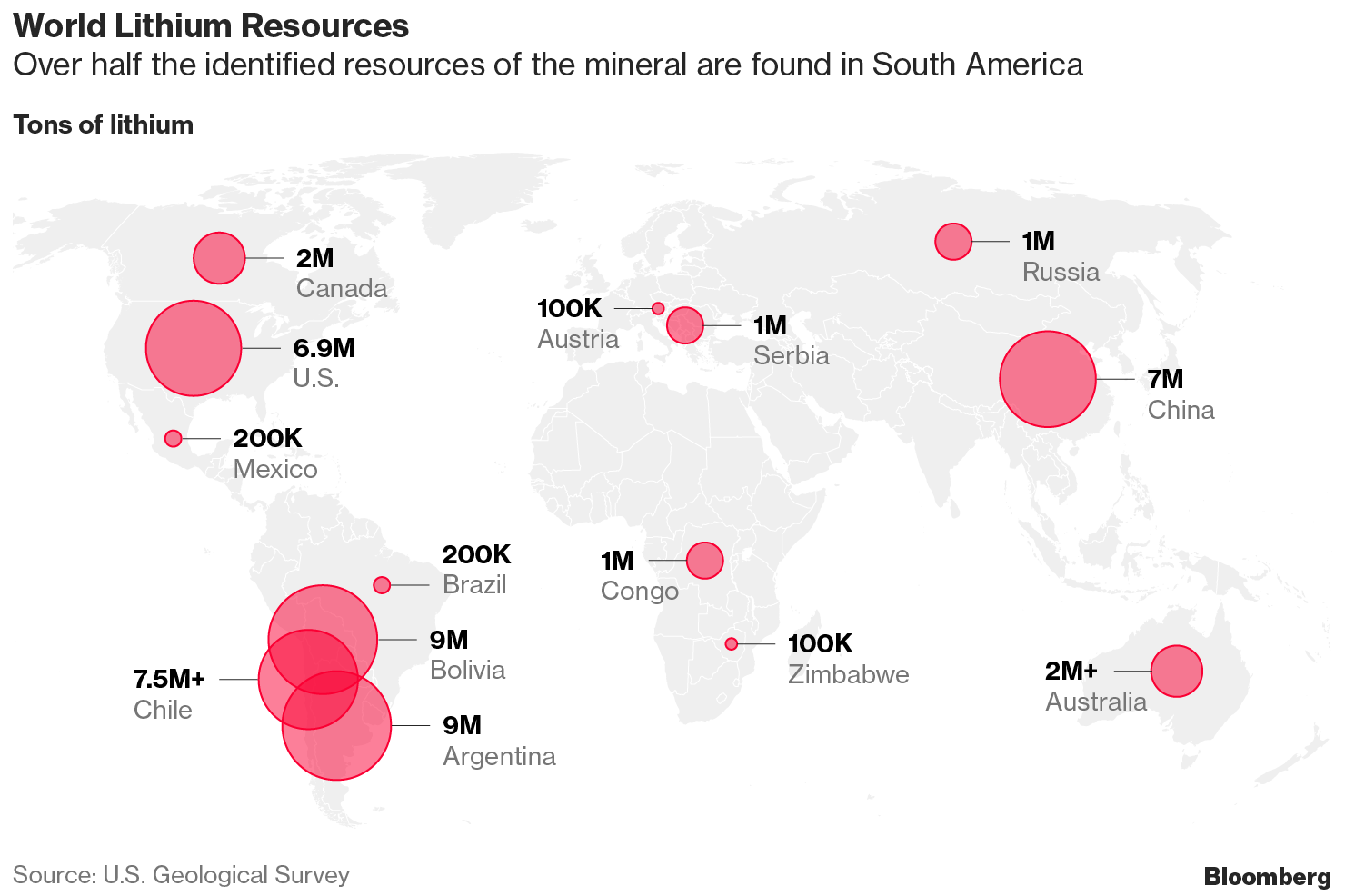

Global lithium production increased by about 12 percent last year, with batteries accounting for about 39 percent of consumption, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. While Australia was the largest producer in 2016, its identified resources are dwarfed by Argentina and Bolivia, each with about 9 million tons and Chile, with more than 7.5 million tons.

“This is not a metal that’s going to be exempt from the normal laws of commodity economics,” said Bernstein’s Gait. “Sooner or later we will over supply.”

There are about a dozen projects being built or expanded around the world, according to Liberum Capital Ltd. Those, plus a handful of others seen as likely to proceed, could help nearly triple global lithium supply by 2025, but still fall short of expected demand.

Beyond that, there’s a further eight projects that haven’t secured financing yet, but could possibly push the market into a surplus by 2025, Liberum said in a report.

Lithium carbonate prices have more than doubled in the past two years, according to data from Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

“With prices where they are right now, there’s not a potential lithium mine in the world that doesn’t make an extraordinary amount of money,” said Liberum analyst Richard Knights. “There’s every incentive to bring supply on.”

In Congo, AVZ must still prove that extracting the lithium is economically viable. It will also need to rehabilitate an old power station to reach production and build over 600 kilometers (372 miles) of roads to connect the mine with the regional capital of Lubumbashi for exports. Still the project is attracting investors, including China’s Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt Co., one of the world’s biggest refiners of cobalt.

“The biggest companies in China are just queuing up,” AVZ Chairman Klaus Eckhof said from Dubai. “They all want to be part of it because they don’t have a pipeline of supply, my phone keeps ringing.”