For more than half a century, Saudi Arabia’s oil minister could move markets with a few choice words about what OPEC may decide at its next meeting, generating millions if not billions of dollars of profit for insiders.

Not anymore. While OPEC’s gatherings still influence prices, it’s not Saudi Arabia’s voice that matters most, but the voice of a non-member: Russia, specifically Vladimir Putin.

Since engineering Russia’s pact with the Organization for Petroleum Exporting Countries to curb supplies a year ago, Putin has emerged as the group’s most influential player. As one senior OPEC official put it on condition of anonymity, the Russian leader is now “calling all the shots.”

The Kremlin’s growing sway within the cartel reflects a foreign policy that’s designed to counter U.S. influence across the globe through a wide mix of economic, diplomatic, military and intelligence measures. That strategy, which is undergirded by Russia’s vast natural-resource wealth, appears to be working.

“Putin is now the world’s energy czar,” said Helima Croft, a former Central Intelligence Agency analyst who directs global commodity strategy at RBC Capital Markets LLC in New York.

Vienna Meeting

The strength of Putin’s position will be in the spotlight on Nov. 30, when OPEC’s 14 members, including Iran, Iraq, Nigeria and Venezuela, host nominally independent producers such as Russia and Mexico in Vienna to discuss whether to extend the cuts past March. At stake is the economic and political health of all states involved, including Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, two former Soviet republics that Putin brought into the deal. Participants in the accord collectively pump 60 percent of the world’s oil.

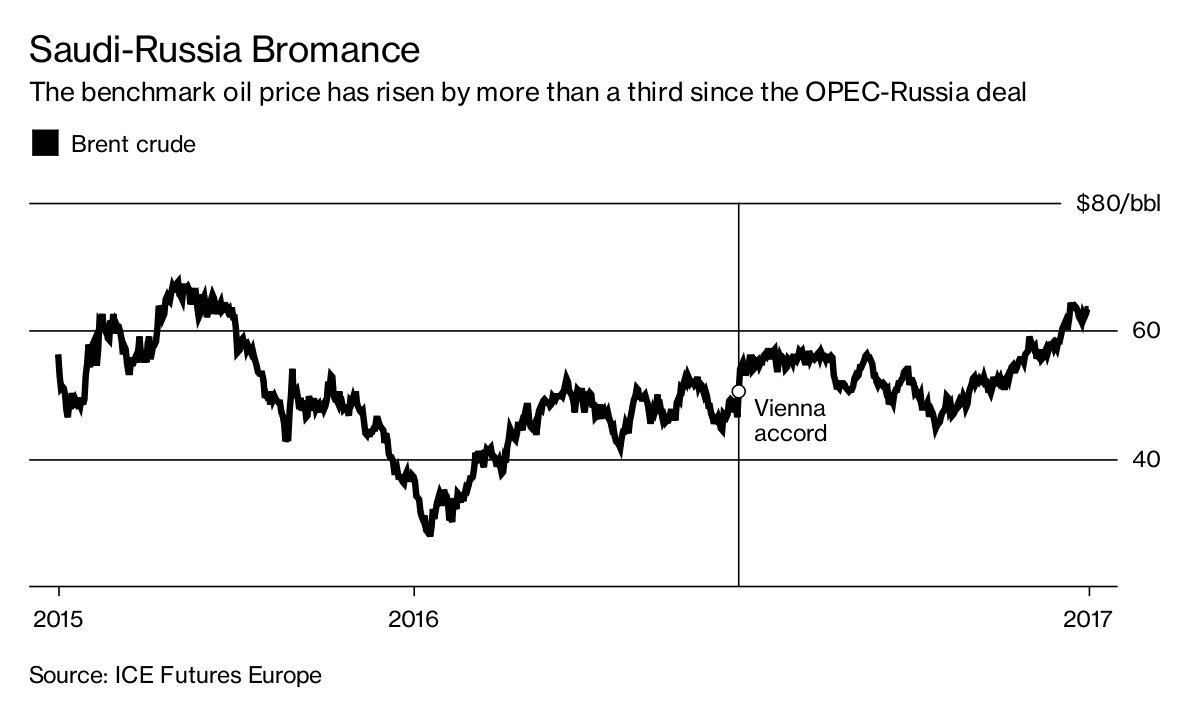

Putin spurred a short-lived spike in prices on the eve of the first-ever visit by a Saudi king to Russia last month by suggesting the cuts be extended until the end of next year, though he stressed he hadn’t made a final decision. Putin’s remarks, though qualified, triggered a fresh rush of diplomacy by both OPEC and non-OPEC producers to try to hammer out a deal.

Since Putin’s comments, the Kremlin has been sending mixed signals, in part to placate domestic oil barons like state-run Rosneft PJSC chief Igor Sechin and Lukoil PJSC billionaire Vagit Alekperov. But it’s also trying to keep oil prices from rising enough to spur shale companies to drill even more in the U.S., which expects domestic production to reach a record 10 million barrels a day next year, a level exceeded only Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Putin, who embarked on his unprecedented alliance with OPEC when prices were about $20 a barrel lower than today and the market looked far more oversupplied, has another reason not to want oil prices to rise sharply. Russia is currently benefiting from a weaker ruble, which benefits exporters, and becoming less dependent on energy sales to meet its spending commitments.

‘Mutually Beneficial’

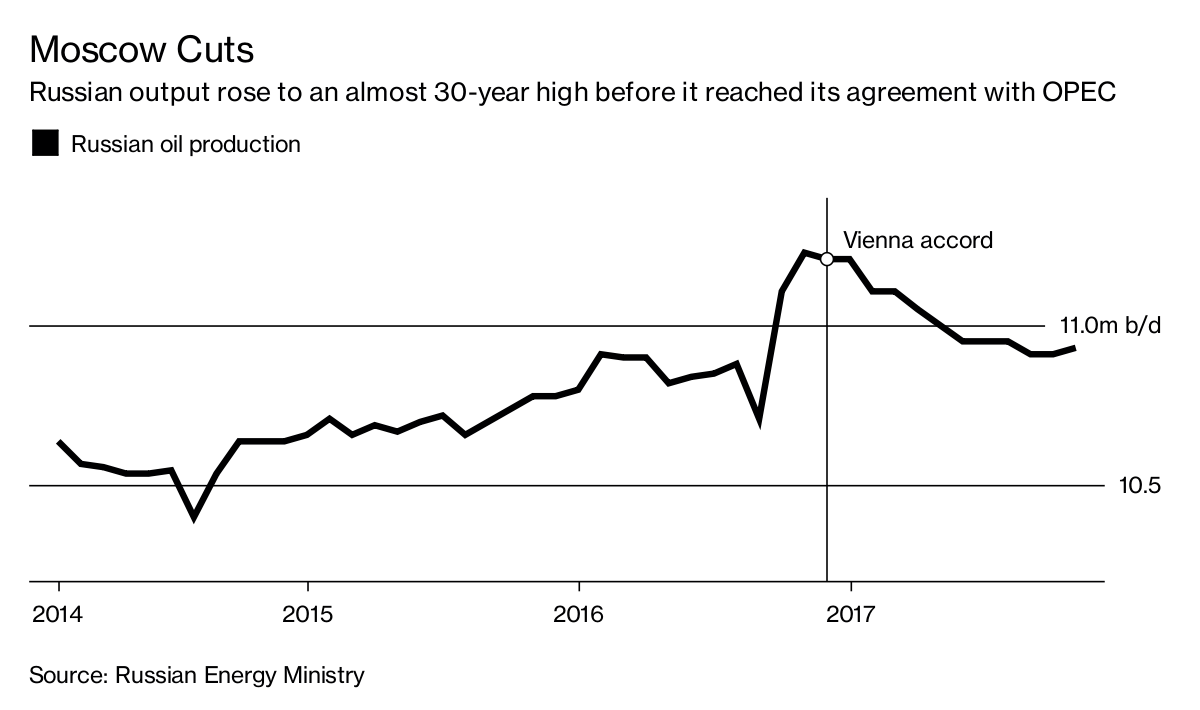

For Russian producers, the cuts are getting increasingly painful. With Brent, the global benchmark, at about $63 a barrel, almost 30 percent higher than a year ago, they’re anxious to start cranking up production. Rosneft this month even said it needs to be ready to open the spigots in December — a surprising date since it’s three months before the current agreement expires.

“There are three scenarios we’re looking at, okay, that the OPEC cuts stop end of the year, end of March next year, or they continue throughout 2018,” Eric Liron, Rosneft’s first vice president for upstream, said on a conference call.

Still, current prices — and geopolitical realities — suggest the accord will be rolled over, according to Edward C. Chow, a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington and a former Chevron Corp. executive.

“It’s mutually beneficial,” Chow said. “The Saudis need a large oil-producing partner to effectively influence the market and the potential for a greater geopolitical and economic role in the Middle East for Russia makes compliance with production cuts an expedient move for Moscow.”

For Saudi Arabia, having to share output decisions with Russia, an ally of its arch-enemy Iran in the Syrian civil war, is a bitter pill to swallow. In the past, the Saudis could impose their will on prices and punish rivals by flooding the market, as they did against other OPEC members in 1985-86, Venezuela in 1998-99 and the U.S. shale industry in 2014-15. Russia was an afterthought.

But now the Saudi economy is reeling and the kingdom needs higher crude prices as much as everyone else. By some measures, including its fiscal break-even point, Saudi Arabia needs even higher prices than Iran or Russia, which is basing its budget for next year on oil averaging $40 a barrel.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s sweeping crackdown on corruption, including the sudden arrests of scores of royals and billionaires, appears to have only increased the kingdom’s newfound reliance on Russia. The purge upended the decades-old model that held the elite together and turned the success of his ambitious economic-reform program into a battle for survival, according to Amrita Sen, chief oil analyst at Energy Aspects Ltd. in London.

“Because of this vulnerability, we believe the kingdom, and more importantly Mohammed bin Salman, needs strong oil revenues — and hence higher oil prices — to ensure he stays in power,” Sen said.