This article first appeared on Bloomberg View and the Bloomberg Terminal.

Earlier this year, Santa Monica-based startup Bird rolled out an app-based fleet of dockless electric scooters in San Francisco. The city is not its first location — it has scooters in Los Angeles, Atlanta and Washington — nor is Bird the only scooter-share company operating there. San Francisco, though, is home to some of the scooters’ most vocal opponents, who see them as sidewalk-clogging nuisances and potential dangers to foot traffic. Proponents (of which I am one!) see scooter sharing as yet another way to move people through cities, and they’re worth analyzing.

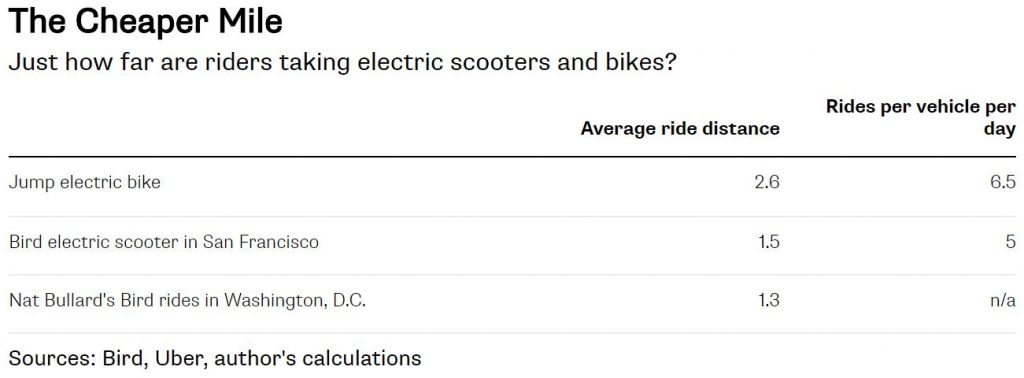

In San Francisco, Bird riders are averaging 1.5 miles per trip. I pulled my own Bird ride data for the month of April (10 rides, all in Washington) and found that I traveled a slightly shorter distance on average. I also spent an average of $2.70 per ride. Jump, the operator of on-demand, pedal-assisted electric bicycles that was recently acquired by Uber Technologies Inc., says that its riders average 2.6 miles per trip.

Bird scooters in San Francisco are being ridden less frequently than Jump bikes are in general but more than the company’s own target of three per day. If San Francisco has its way, the city’s total scooter fleet would be capped at 1,250 for six months — a figure lower than Bird’s own fleet, much less the total fleet including Lime and Spin scooters. For the moment, the market seems overserved.

These scooters certainly aren’t toys; they can be a nuisance if riders don’t follow some basic rules. But my average speed during those April rides of 7.5 miles per hour was almost a third faster than the 5.7 mile-per-hour average speed of a city bus in Manhattan. Average rides are shorter than on Jump’s bikes, and the scooters aren’t great at steep inclines.

What they are great at, though, is being a last- or only-mile option for quick, inexpensive movement. Like electric bicycles, the scooters accelerate briskly. Unlike bicycles, they’re friendly to pretty much any attire. (Also unlike pedal-assisted electric bicycles, scooters require riders to have a driver’s license, as scooters have a throttle.) Scooters are also easy to dispatch: A delivery van can hold a lot more charged scooters than bicycles, and that makes them easier to move to where and when they’re most in demand.

Neither Uber nor Lyft Inc., nor any of their competitors, seem interested in the electric scooter market — yet. But Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi hinted last month where his company or its peers might become interested. He said the average trip distance wasn’t much different from the average distance of an Uber car ride. If scooter rides begin to encroach on that figure, or they induce significant new demand for electric travel at their existing average distance, then perhaps a scooter firm will be an acquisition target.

Khosrowshahi also said that Uber “aims to provide a variety of transportation options to consumers.” Perhaps that’s the best way to think of scooters and whatever novel electric transport follows them: as flexible transport options a rider doesn’t need to own, can always access, and will select based on that day’s needs and wants.