This article first appeared on Bloomberg View and the Bloomberg Terminal.

By Nathaniel Bullard and David Fickling

BHP Group, a diversified mining company and the largest company by market cap on the Australian Stock Exchange, recently published its economic and commodity outlook for the host of metals and hydrocarbons it produces. Its forecast for coal points to changes ahead for the world’s second-largest source of primary energy, after oil.

The BHP outlook for energy coal notes weak prices for Australian exports. And, looking further out, BHP refers to global population growth as its benchmark and concludes:

Longer–term, we expect total primary energy derived from coal (power and non–power) to expand at a compound rate slower than that of global population growth. Coal is expected to progressively lose competitiveness to renewables on a new build basis in the developed world and in China.

The company adds that thermal coal, the cheapest power option in many markets for decades, is under pressure from renewable energy, though it expects one giant market — India — to remain competitive:

In our view, the cross over point should have occurred in these major markets by the end of next decade on a conservative estimate. However, coal power is expected to retain competitiveness in India, where the coal fleet is only around 10 years old on average, and other populous, low income emerging markets, for a much longer time.

The thing about using population growth as a benchmark is that it doesn’t leave much room for any sort of growth for coal use at all. The United Nations, in its latest World Population Prospects, expects population to grow just a hair over 1% this year, based on its medium variant for fertility. The UN’s low-fertility variant has the population shrinking by mid-century. Benchmarking to below a growth rate of 1%, and declining from there, sounds not far off from expecting no growth, or negative growth, in perpetuity.

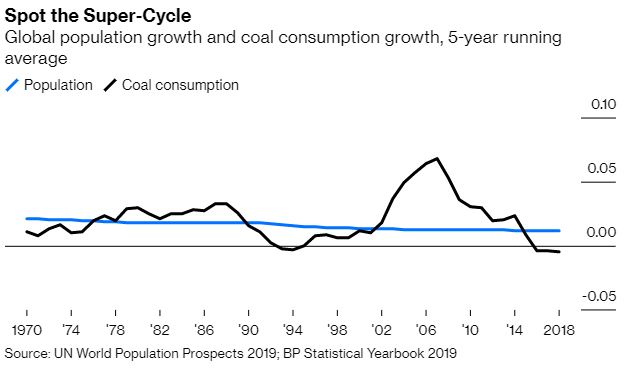

There have already been periods when growth in demand for coal has not only dipped below population growth, but has been negative. Using data from BP, the oil major which has published data on coal consumption since 1965, we can see that the growth in demand for all coal uses (power, industrial and steel-making applications) lagged behind population growth in the 1970s and in the 1990s, based on a trailing 5-year average, and is doing that again right now.

The two long periods in which growth in coal demand exceeded population growth were both exceptional times, too. The first, in the very late 1970s through most of the 80s, was the result of the 1973 Arab oil embargo, when U.S. and European generators switched from oil to coal. The second, in the early 2000s, reflected the extraordinary surge in China’s appetite for coal for power, industry and steel-making.

BHP’s outlook is fairly mainstream, in reality. The International Energy Agency, which tends to overestimate coal demand, sees no global demand growth to 2023, the end date of its latest global coal outlook.

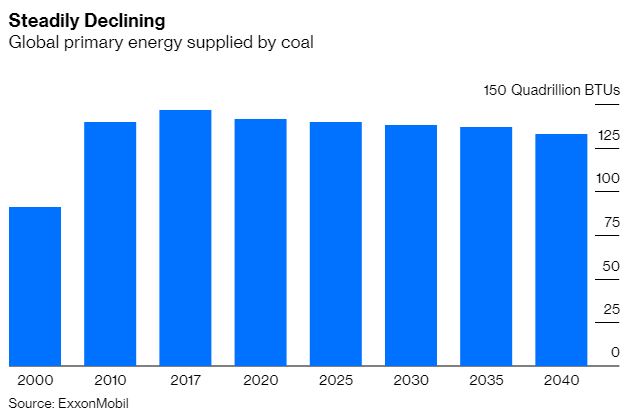

Another huge energy company is clearer about a decline in demand. ExxonMobil, in its outlook published this week, says that coal’s contribution to total primary energy supply has already peaked.

The bull case for thermal coal, such as it is, isn’t so much about demand rising overall as it is about increased demand in Asia offsetting the collapsing demand in Europe and North America. The coal industry is hoping India or Southeast Asia will provide another one-time boom to match the two previous exceptional events, but both of those instances came at a time when coal was the cheapest available technology. That’s no longer the case in most markets.

BHP’s strategy matches its outlook. The company is getting out of thermal coal, and its former unit South32 is selling its South African thermal coal mines. The CEO of Colombian coal producer Cerrejon, jointly owned by BHP, Glencore Plc and Anglo American, says the market for its coal is disappearing. Another coal miner, South Africa’s Exxaro Resources Ltd, plans to extract “as much value as quickly as possible” from its existing business while planning clean-power initiatives.

At the same time, BHP will remain by far the biggest producer of the metallurgical coal used in steel-making for the foreseeable future. But demand for metallurgical coal may come under pressure eventually, too.

BHP’s main products are iron ore and metallurgical coal, used in primary steel-making in blast furnaces. Any change in primary steel demand, resulting from changes in the global economy or from improvements and increases in secondary, recycled steel production, would be felt.

After 2025, an enormous amount of scrap steel in China will begin hitting the market for the metal. When that happens, electric arc furnaces (which do not use coal, and which can use electricity from low- or zero-emission generation) could seriously undermine the economics of primary steel production in blast furnaces.

That happened in the U.S. in the 1980s and 1990s, when Nucor Corp’s electric arc-produced steel undermined the country’s primary steel industry. China has produced half the world’s steel for years, most of it for domestic consumption; so supply and demand will be there.

There’s another factor to consider: carbon emissions. In July, BHP CEO Andrew Mackenzie said that the company will not only aim for net zero emissions in its own operations, but also in “Scope 3” emissions from its value chain. Primary production of a metric ton of steel generally emits less carbon dioxide than burning a ton of thermal coal, but not much less. If the company is serious about Scope 3 emissions, then it should be serious about steel, too.

BHP’s position on Scope 3 emissions is high-stakes move, considering what it produces and what those products are used for. One option for BHP would be to use its petroleum unit to develop hydrogen-reduced iron for primary steel-making in electric furnaces. BloombergNEF’s latest research finds that the steel industry could use hydrogen instead of fossil fuels for as much of half of global output by 2050.

Coal demand for power and industry may be declining, and metallurgical coal might be the black stuff’s last fortress. A mountain of scrap, and new technology, might eventually surround that fortress, too.