This article first appeared on Bloomberg View and the Bloomberg Terminal.

T. Boone Pickens, the legendary American oil entrepreneur who died this week at 91, was known for his aggressive corporate plays in the 1980s and the oil and gas investing strategies that earned (and sometimes lost) him billions since the 1990s. He also had a vision for America’s energy future. His 2008 Pickens Plan thoughtfully delineated which resources needed to flow, and where, to make the U.S. energy-independent.

Last week, as it happened, I was at Pickens’s Mesa Vista Ranch to talk to investors and industry executives about how fast the energy system is changing, thanks to new technology — some of it envisioned by Pickens, and some not. Reflecting now on Pickens and his plan, I’m struck, first, by his boldness in imagining a changed energy future and, second, by how quickly things shifted in ways even such a visionary could not foresee.

At almost the exact moment the Pickens Plan debuted, oil prices hit their all-time peak of $147 a barrel. They’re now hovering about $90 a barrel lower.

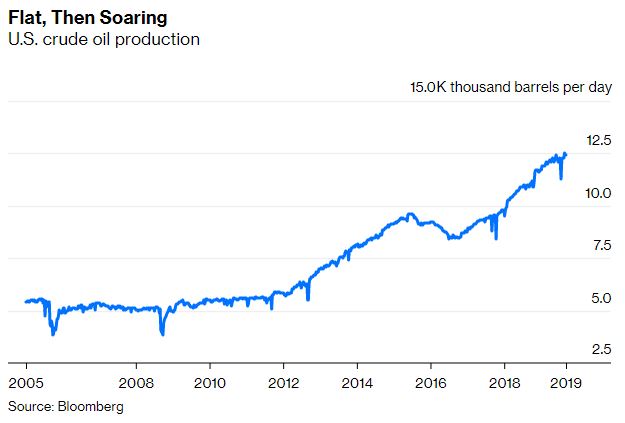

As Pickens mentioned in his whiteboard presentation, the U.S. was then importing most of the oil it consumed. U.S. production amounted to a little over 5 million barrels a day. Since then, thanks to the hydraulic fracturing revolution, oil production has more than doubled.

And natural gas production has risen almost 60%.

In 2008, as Pickens noted, half of America’s electricity supply came from coal, a share that has since fallen to 27%. In the Pickens Plan, wind and nuclear power were expected to displace gas-fired power, so that gas could be shifted into transportation. Solar energy and electric vehicles were not even mentioned. Now, both natural gas and wind have become alternatives to coal, while the biggest disruption for oil has been new technology in the oil business itself.

Pickens got the wind industry wrong, by his own rather salty admission. But, that’s not a criticism of his plan. (As he pointed out, he wasn’t really wrong, just early.) It’s a testament to the man’s forward thinking that he could see natural gas as an alternative to oil, and wind as a major source of power.

A new research paper from the World Economic Forum has an elegant framework for thinking about such energy transitions: They differ according to whether you consider the big picture of global supply and demand, or the change that happens at the margins of both. The authors describe these two narratives as “gradual” and “rapid.”

The gradual narrative, the authors say,

… “is that the energy world of tomorrow will look roughly the same as that of today. Gradual scenarios extrapolate current patterns of policy, industry, consumption and investment, thus supporting planned carbon-intensive investment decisions and implying that the global energy system has an inertia incompatible with the Paris Agreement.”

The rapid narrative, on the other hand,

… “is that new energy technologies are rapidly supplying all the growth in energy demand, leading to peak fossil fuel demand in the course of the 2020s. Rapid scenarios suggest that current technologies and new policies will reshape markets, business models and patterns of consumption, challenging planned carbon-intensive investment and leading to a low-carbon global economy while creating considerable economic and social benefits.”

The difference is explained by the fact that total global energy supply is immense and grows only about 1 to 2% per year. In 2017, total primary energy supply was 13,475 million metric tons of oil equivalent; the change in supply was 246 million metric tons of oil equivalent. A focus on the former makes it hard to see not only that change is happening but also that change is possible.

Last year’s growth in supply was unusually high, but more than a third of it came from renewable energy. If total supply had grown only as much as it did in 2015, then renewables would have been all new supply. In other words, the implications of rapid change are significant.

No one sets out to get things wrong, of course, least of all Pickens, who spent $100 million of his own money on his plan. Some questions have yet to be answered — and big changes are underway — even in large and established systems like energy. Rapid changes are happening even faster than their proponents expected.

Pickens was also an avid Twitter user to the very end. Seven years ago, the recording artist Drake tweeted that “The first million is the hardest.” Pickens, who had made and lost far larger amounts many times over, had this response: