By Victoria Cuming, Head of Global Policy and Maia Godemer, Senior Associate, Sustainable Finance, BloombergNEF

On the brink of this year’s United Nations climate summit, COP29, governments are grappling with how to devise their next climate plans. These are meant to include bolder pledges and explain how policymakers intend to achieve them. They also need to account for budgetary constraints, a cost-of-living crisis, the wish for energy independence and use of domestic natural resources – and, very apposite for this week, election outcomes. But BloombergNEF analysis suggests that some Group-of-20 governments have made headway on implementing robust policies to tackle climate change, others have not.

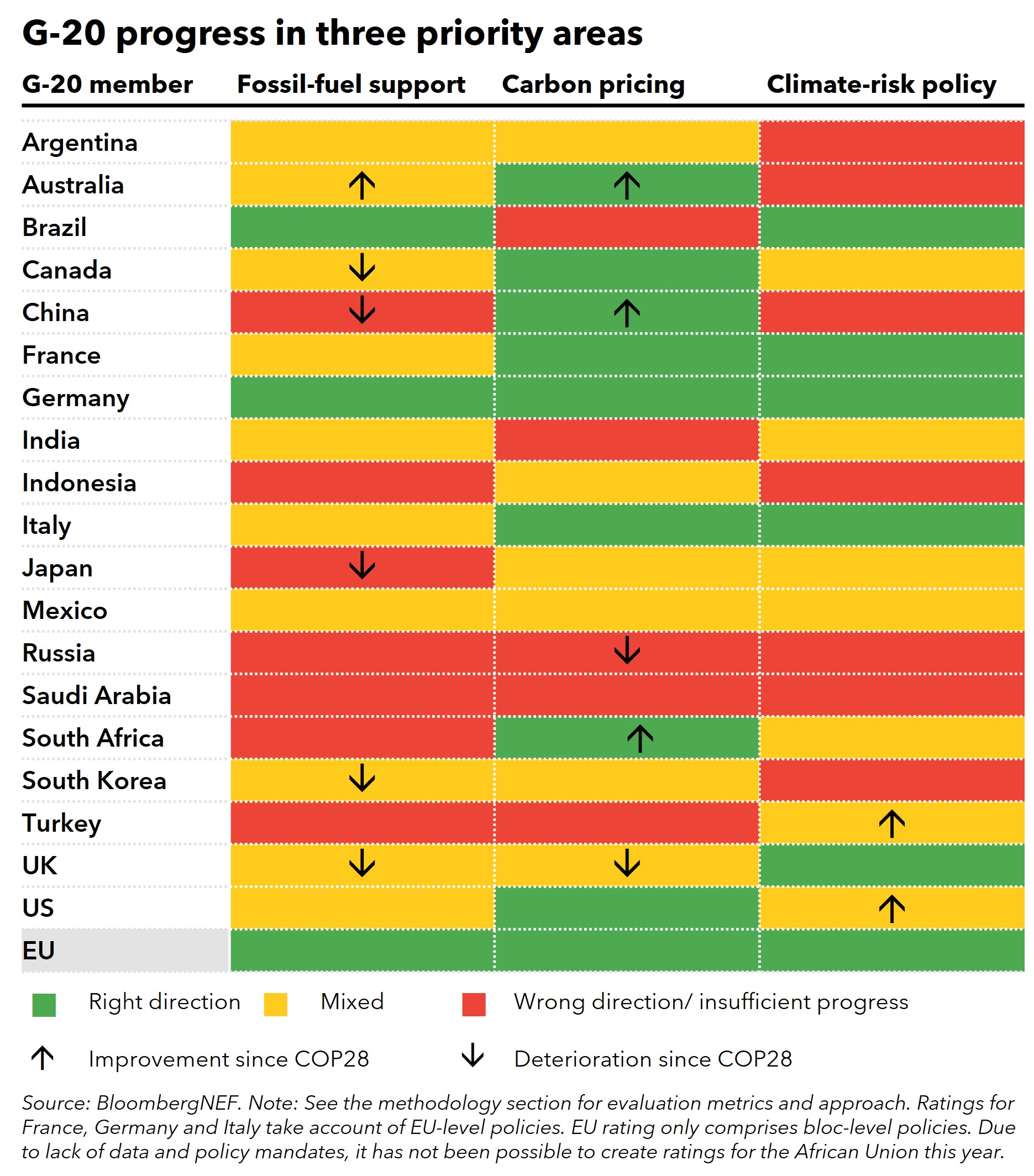

This fifth edition of BNEF’s Climate Policy Factbook, commissioned by Bloomberg Philanthropies, assesses the G-20’s performance in three green policy areas that would accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy without considerable government outlay: fossil-fuel subsidies, carbon pricing and climate-risk policy.

Fossil-fuel support remains above historical levels

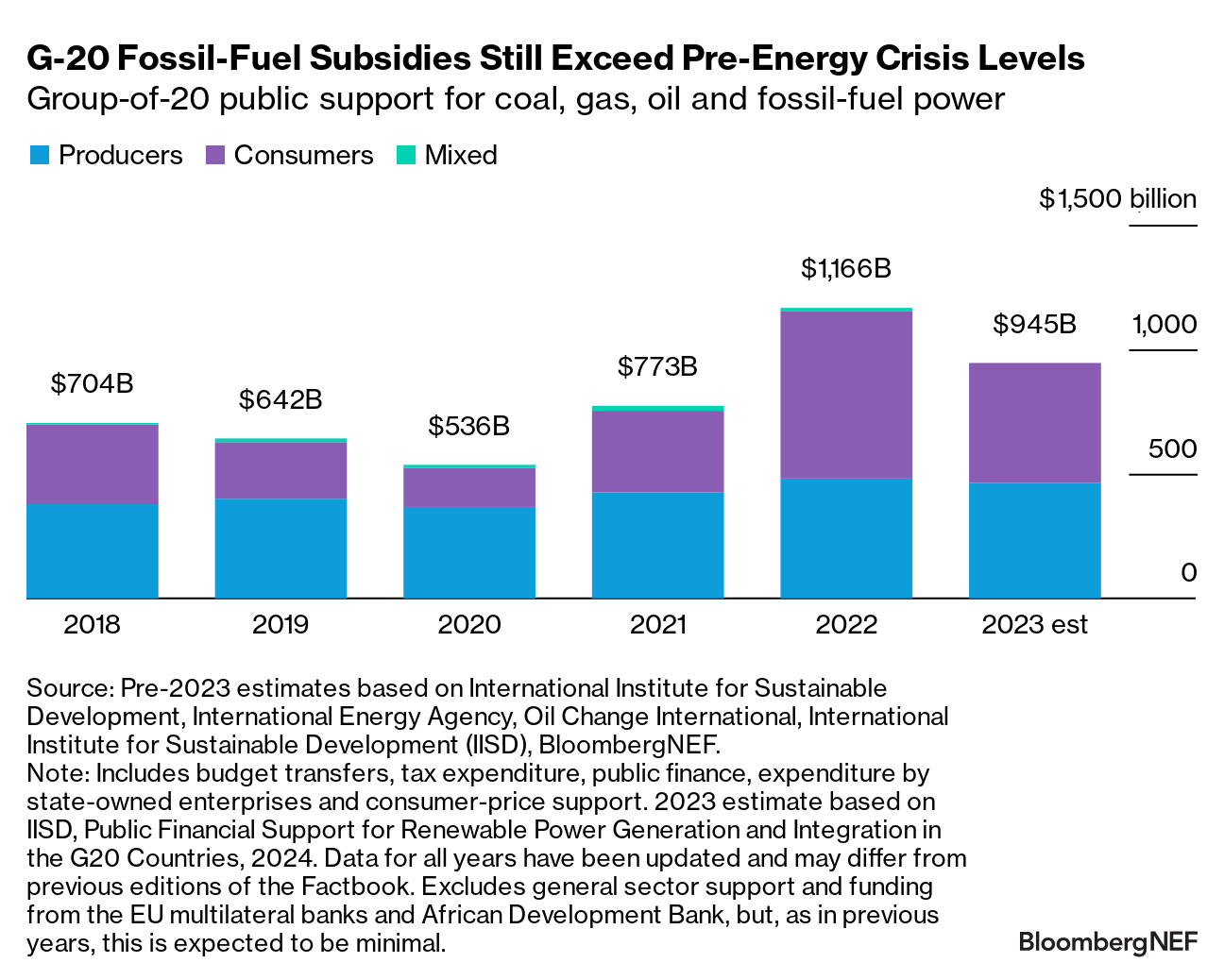

G-20 governments and state-owned bodies provided $1.1 trillion in fossil-fuel support in 2022 – by far the highest volume for at least a decade. The main driver of this increase was the global energy crisis as policymakers sought to support consumers. However, $500 billion went to producers and utilities, some of which saw record profits that year.

The G-20 continues to expand its coal-fired power fleet, increasing generating capacity by 3% over 2019-2023, including all members of the EU and African Union. As a result, it has around 2 terawatts of operational coal-fired generating capacity, with another 0.6TW in the pipeline. This fuel is the largest contributor to climate change, highlighting the importance of ending coal-power build and phasing out existing assets. There is a clear divide between developed economies and emerging markets: by 2023, G-20 members in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development had cut coal-fired capacity by 22%, on average, relative to 2019 levels, compared with a 6% increase for non-OECD economies.

As a result of these trends and a lack of progress on phasing out coal power, China and Japan are now classified in the Climate Policy Factbook as making insufficient headway on fossil-fuel support, while Canada and the UK have shifted down to ‘mixed progress’. But Australia is now moving in the ‘right direction’, having reduced coal-fired generating capacity in recent years and lowered fossil-fuel support in 2022.

Country-level data is not yet available for 2023 fossil-fuel subsidies. But early estimates suggest the G-20 provided $945 billion in support for coal, gas, oil and fossil power. This marks a 19% year-on-year fall but still well above historical levels – even though the acute phase of the energy crisis generally ended in late 2022. Subsidy reform is politically delicate, especially if it implies an increase in consumer prices. As a first step, policymakers could follow Canada’s example by defining what inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies are and requiring new government programs to avoid them.

Most carbon pricing programs are weak green incentives

A growing number of G-20 members have multiple carbon taxes and markets either in place or planned. Compliance carbon pricing now covers 29% of G-20 emissions and this share is due to climb as programs are expanded and new schemes begin. Indeed more G-20 members are planning to have multiple carbon taxes or markets.

Price trends have varied across these economies in the last year: some European programs have seen falls, while Australia, China, South Africa and some US state-level markets have shifted higher. However, many carbon-pricing policies are weak green incentives: only the European Union’s emission-trading scheme is within the range of prices estimated to be needed in 2030 to be on track to limit global warming to 2C, although Canada and California could be in line by the end of the decade. Another reason is the continued generous concessions to participants, including the handout of free emission allowances, though some governments are devising reforms.

Governments make incremental headway on climate-risk policy

The gap widens between the G-20 members at the vanguard of climate-risk policy and those lagging behind. Some, like the EU, Brazil and the UK, have made substantive progress in introducing regulations. But others, including Argentina, Saudi Arabia and Russia, lack rules requiring firms and financial institutions to assess, report and mitigate their exposure to climate-related risks. Having made significant progress in the last year, Turkey and the US have moved up to the next rating category.

The International Sustainability Standards Board’s framework issued last year has enabled many policymakers to adopt the harmonized reporting standards in their own jurisdictions. Nine G-20 markets have passed, or said they were developing, local rules to mandate reporting against the ISSB standards. But while this creates a unified approach to climate-risk reporting, the framework’s lack of stringency, as well as fragmentation due to the local variations, could reduce its effectiveness.