By Angus McCrone

Chief Editor

Bloomberg New Energy Finance

It seems that what I did in the 1970s is suddenly catching up with me. Or, at least, so says my dentist. My choice of sugary drinks back then, and the resulting low-tech fillings, mean that nowadays I brace myself for trouble every time I bite into a baguette.

Long-term effects also unfold with the energy system. Decisions made in one year can have a profound impact on how power is generated and transport is fuelled, several decades later.

So it is not as illogical as it sounds to ask this: how did the globally energy system in 2040 change in the year 2015-2016?

In some years, the answer might be not a lot. But 2015-2016 has been different: there have been dramatic shifts in the fundamentals that affect long-term power generation decisions. Some of these have been outside the energy system, but several others have been at the heart of it.

I will come to those in more detail below but, to mention a few headlines up front, there are the shrunken cost of fossil fuel commodities, the rise of electric vehicles and the consequent slide in lithium-ion battery prices – plus, most strikingly, the tumbling costs of wind and solar power around the world. The latter change has been highlighted by tariffs agreed for projects in Dubai, India, Peru, Mexico, Morocco and, most recently, Zambia.

Big shifts such as these have prompted the world’s leading forecasters to rethink some of their predictions for the evolution of energy to 2040. For instance, the International Energy Agency, in its World Energy Outlook 2015, published last November, raised its estimate for generation from non-hydro renewables in 2040 to 19 percent, from the 17 percent it had said a year earlier; and ExxonMobil, publishing its outlook in January this year, raised its estimate for the electric vehicle share of the global light-duty vehicle fleet in 2040 from almost nothing in its January 2015 energy outlook to about 4 percent in the January 2016 version.

However, the boldest response has arguably come from my colleagues at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, as they have incorporated the impact of 2015-16 into their latest long-term forecast for the electricity system – New Energy Outlook 2016, published on June 13. BNEF’s team of 65 analysts who worked on the forecast have delved deep into the cost trends for all power generation technologies and the likely evolution of electricity consumption in economies at different stages of development.

New NEO

Here are seven of the key changes in NEO 2016 compared to its predecessor last year:

1. Wind and solar costs are going to fall even more quickly over the next 25 years than we had previously estimated. Levelized costs of generation for onshore wind and photovoltaics will drop by 41 percent and 60 percent respectively in the period to 2040, taking our global average estimates for the two technologies in 2040 to $46 per megawatt-hour and $40 per megawatt-hour1. The previous year, we had predicted cost reductions of 32 percent for wind and 48 percent for solar.

The reasons we now expect wind to get 19 percent cheaper for every doubling of capacity include faster include turbine size and efficiency, resulting in rising capacity factors, as well as economies in manufacture and reduced operating and maintenance expenses. The reasons we expect solar PV to get 26.5 percent less costly for every doubling of capacity include several of the same factors, plus increases in panel efficiency and a big shrinkage in capex disparities between different countries.

2. Coal and gas prices are going to be much lower over the long term than we had previously thought. In fact, NEO 2016 has a track for coal prices that is 33 percent lower than the one contained in NEO 2015, and its track for gas prices is 30 percent lower. Behind these changes are developments in those commodity markets over the ensuing 12 months, and new forecasts for demand in the next 25 years, notably lower consumption of coal in China. The projections also take into account the likely capacity factors of coal- and gas-fired power stations around the world in an era of transition to variable generation sources.

The impact of those lower costs for coal and gas on the power mix is much less than might appear likely at first sight. That is largely because, even if fossil-fuel generation proves to be cheaper than previously thought over the next 25 years, so will wind and solar.

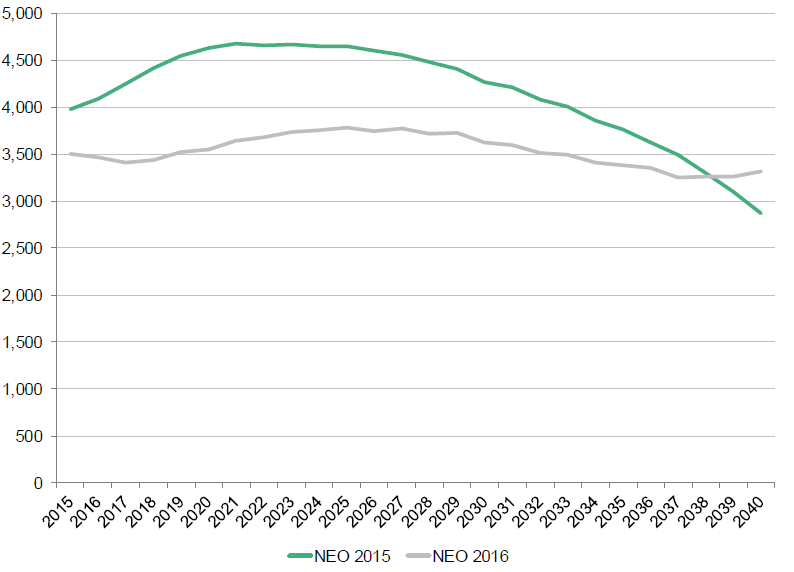

3. China’s electricity consumption and emissions path to 2040 is significantly different from what we projected a year ago. Electricity demand, according to NEO 2016, will rise 75 percent between 2015 and 2040, whereas the previous forecast only said 56 percent, and emissions in 2040 will be higher than previously projected. However, this will owe much to the take-off of electric vehicles there in the 2030s, and actually in the interim both power demand and emissions will be much lower than we said in NEO 2015. For instance, for 2025, we now say that Chinese power generation emissions will be 3.8 gigatonnes, not 4.7 gigatonnes.

This change reflects the ongoing slowdown in China’s economic growth and its push for renewables, and the net effect is that for most of the 2015-40 period, it will be contributing significantly less to climate change that we had previously estimated. The difference over the 25 years will in fact be nearly 16 gigatonnes fewer of CO2 released.

4. That makes India even more crucial to the fate of global attempts to curb emissions. NEO 2016 forecasts that the south Asian country will increase electricity demand between 2015 and 2040 by 298 percent, and emissions by 215 percent, over the period. It will be taking advantage of abundant ultra-cheap domestically mined coal as well as investing $611 billion in hydro, wind, biomass and – especially – solar. Its total emissions over the 25 years will be 1.6 gigatonnes more than we estimated in NEO 2015, largely because of an upward adjustment in our projection for India’s electricity demand growth. BNEF will look in more detail at India’s energy choices in July’s VIP Comment article.

5. Electricity demand everywhere, including China and India, will get a boost from the acceleration of the EV market. BNEF predicted in February that electric cars would take 35 percent of global light-duty vehicle sales in 2040 (far above Exxon’s prediction of “less than 10 percent”). They would account for 25 percent of the total fleet, spurred on by steadily improving economics relative to gasoline-fuelled cars, as battery prices slide – and slide – in line with experience curve effects. NEO 2016 translates that into electricity demand, and finds that that EVs will be responsible for 8 percent of global electricity demand by 2040. No wonder the world’s utilities are starting to have a warm feeling about electric cars.

6. Batteries are going to be a huge story, in partnership with small-scale solar. Falling costs, initially at least for lithium-ion technology, will enable those with PV on the roof to put storage into the attic or basement, or the corner of the warehouse, and thereby make full use over a longer period of the kilowatt-hours of electricity produced by their PV panels during the sunny hours. By 2040, the world will have installed some 759 gigawatt-hours of batteries for behind-the-meter applications, compared to almost none today, and the cumulative amount invested will have been $250 billion, according to our forecasting team.

7. Repowering of wind farms is going to become a significant part of investment activity. NEO 2016 shows decommissioning of obsolete or poorly performing wind projects rising from almost nothing today to more than 20 gigawatts per year by the end of the 2020s and 50 gigawatts per year by 2039. By contrast, fresh investment in sites that have performed well and merit a capacity boost will climb to reach 60 percent, or 52 gigawatts, of the 86 gigawatts of onshore wind power added in 2040. In total, wind repowering will involve investment in the 2016-40 period of no less than $1.4 trillion.

Bill for two Degrees

NEO 2016’s climate projection is a bit less bleak than its predecessor – in the same way that crossing a four-lane highway is a little less daunting than crossing a five lane highway. But, whether four or five lanes, the dangers still look acute.

A year ago, Bloomberg New Energy Finance said that annual power sector emissions in 2040 would be 10 percent higher in 2040 than in 2015; now our team says that they will be 5 percent higher. There will be 36 gigatonnes fewer of CO2 going into the atmosphere over the forecast period than we said in NEO 2015, but that is as good as the news gets. Our analysis still shows that emissions will not peak until 2027 – at a level 6 percent above the 2015 figure – and they will hardly fall at all in the ensuing 13 years.

That prospect looks even worse than it would have done a year or two ago – because the underlying climate data appear to have worsened. The proportion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, as measured in Hawaii by the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration, jumped 3.05 parts per million in 2015, the biggest increase in 56 years of measuring, and in May this year, it averaged 407.70ppm, up 3.76ppm on 12 months earlier. At that rate, the Earth would be right up to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change’s 450ppm “safe” limit in just 11 years’ time.

What would it take to bring emissions down onto a path compatible with the CO2 content never going above 450ppm? Well, NEO 2016 estimates that total world investment in power generation capacity between now and 2040 will be $11.4 trillion, with $7.8 trillion of that destined for renewables, and $1.5 trillion for nuclear. To cap CO2 at 450ppm would require the investment of an additional $5.3 trillion on zero-carbon generating capacity between now and 2040.

This extra $5.3 trillion will not be delivered on the basis of power generation economics and current policies and targets, according to the NEO model. So, to make it happen, there would have to be far more ambitious policies set by the world’s major emitting countries. Despite the achievements of COP-21 in Paris last December, it is hard to be optimistic that this level of additional finance – or anything like it – will materialize.

Wider changes in the world

Of course, shifts in energy system fundamentals are not the only things changing around the globe. There are economic and political shifts going on that may be helpful, or unhelpful, to the chances of getting that additional policy action to boost investment in zero-carbon power.

For one, there has recently been another lurch downwards in global interest rates (since summer 2015, for instance, the yield on the 10-year German government bond has fallen from 0.6 percent to a previously unimaginable minus 0.1 percent). This is bleak news for the world’s savers but, if rock-bottom interest rates are sustained, they could help to underpin the competitiveness of renewables such as wind, solar and hydro because they minimize the financing cost of capex-intensive projects.

Another one is the political undercurrent in many developed economies. The U.S. is heading for perhaps its most acrimonious presidential election contest ever, with one candidate appearing to reject the scientific consensus on climate change, as well as the political consensus on other issues. In continental Europe, establishment parties are under siege from populist movements intent on raising barriers to migration and perhaps even to trade. And in the U.K., of course, the June 23 referendum concluded with a market-shaking vote in favour of quitting the European Union.

As we argue in an Analyst Reaction about that referendum, the result has few direct implications for clean energy in the U.K., but it may well have indirect effects – via disruption to the economy and changes to the make-up of the government – that will make life even tougher for clean energy investors over the next few years than it was already likely to be under the now-outgoing Prime Minister, David Cameron. U.K. Politics has run into a ‘Summer Crisis’, the results of which could hardly be more uncertain.

So, am I optimistic or pessimistic? On the U.K, sufficiently pessimistic about the economy and a deeply split population to suspect that a compromise to satisfy as many as possible of the young and the old, London and the provinces, rich and poor, cosmopolitan and left-behind, will have to be sought with greater urgency than is yet appreciated.

On global clean energy, optimistic about the ability of solar, wind, storage and efficiency technologies to evolve and out-compete the incumbents. On climate change, not so optimistic.

On my dental outlook, pessimistic.

China power generation emissions, 2015-40, megatonnes

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance

1 In 2015 dollars.