By Nat Bullard

Senior Contributor

BloombergNEF

Energy transition investment exceeded $1.1 trillion dollars in 2022, and for the first time equaled investment in upstream oil and gas and unabated fossil fuel-based power generation. Investment increased more than 30% year-on-year, with investment in renewable energy up 17% and investment in electrified transport up more than 54%.

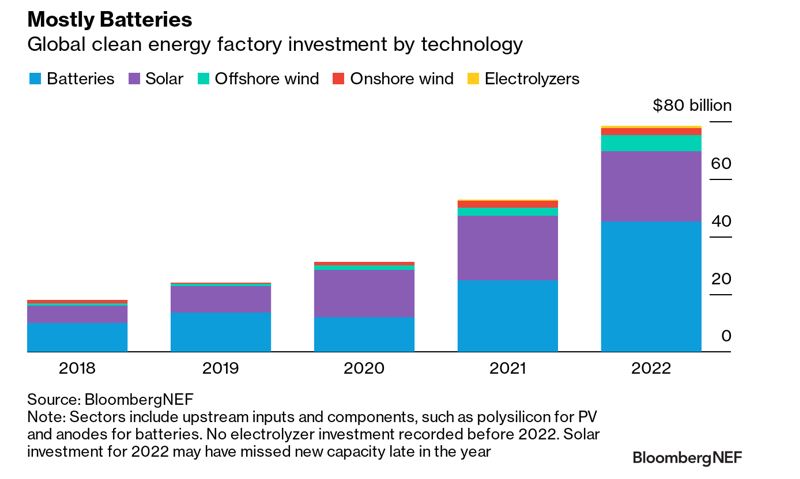

One aspect of the energy transition is growing even faster than that rapid topline – investment in the factories producing the solar modules, wind turbines, batteries, and electrolyzers that are installed in grids and networks worldwide. Investment in clean technology factories reached just under $80 billion in 2022, up 44% year on year, and a four-fold increase since 2018. Recent global industrial policy developments suggest that last year’s figure is only the beginning of a years-long capacity expansion in the world’s biggest economies.

Today’s clean energy manufacturing investment is highly concentrated in a few sectors. Two products, batteries and solar modules, were 88% of total investment in 2022, down from a high of 95% in 2019. Offshore wind investment has grown from $800 million to $5.8 billion in five years, onshore wind from $900 million to $2.6 billion, and electrolyzers from zero in 2020 to $800 million in 2022, but these sectors represent a very small share of total capacity expansion investment.

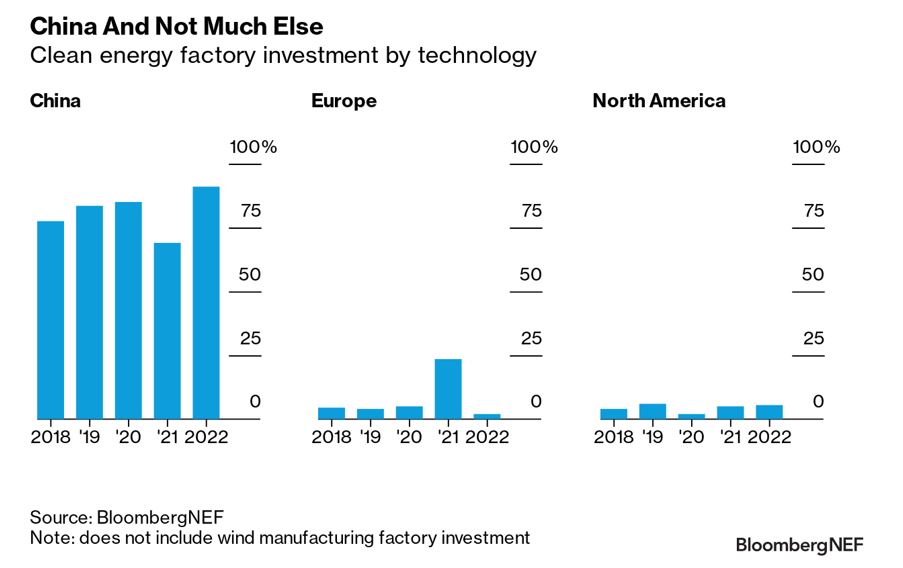

If clean technology manufacturing expansion has expanded around just a few sectors, it is even more concentrated by geography and focused on a single market – China. Five years ago, China took in more than 77% of total manufacturing investment dollars; last year, it received more than 90% of investment in a market four times larger than a half-decade earlier. The substantial disruptions of Covid-19 dropped China’s share significantly in 2021, with Europe receiving nearly a quarter of investment that year. But with that exception, China’s investment in clean technology manufacturing capacity in recent years is between eight and 10 times more than North America and Europe combined.

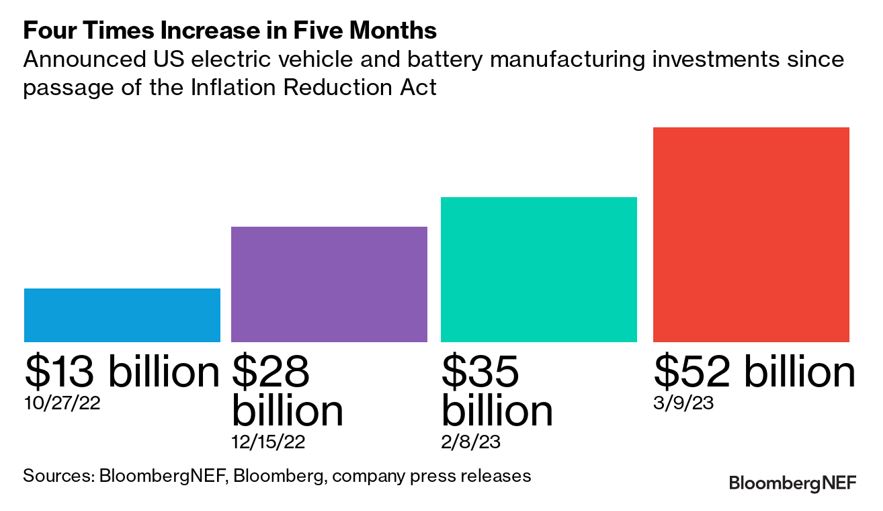

With the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, US clean technology manufacturing has been supercharged. The US automotive and battery sectors have announced $52 billion in planned new factories since the IRA passed in August of 2022, with half of that outlay for battery production alone. That is more than 20 times the amount announced in 2021. As the CEO of Volkswagen’s Scout brand said in March when announcing its $2 billion factory in South Carolina, “there’s never been a better time to build a factory in America.”

The IRA (and the CHIPS and Science Act, aimed at enhancing US competitiveness in semiconductors) have not just re-written policy. They have changed where, and how, companies invest. The long timelines of the IRA’s support mechanisms have given manufacturers confidence to expand on multi-year timelines, and the total addressable markets for clean power generation equipment, hydrogen electrolyzers, and electric vehicles are large enough to support major expansion.

US industrial policy largesse, and the speed with which it has spurred investment commitments, has not gone unnoticed, particularly in Europe. As of January of this year, European Union officials were concerned that the IRA essentially discriminated against EU firms. The EU has, though, constructed its own policy response.

Last month, the European Union announced its Net Zero Industry Act, which BloombergNEF head of trade and supply chains analysis Antoine Vagneur-Jones describes as the bloc’s “rallying cry for onshoring clean energy manufacturing.” (BNEF clients can view the full report here.) The NZIA sets a minimum goal that EU factories be capable of meeting 40% of demand for key products such as solar modules, wind turbines, batteries, and hydrogen electrolyzers. The legislation must now pass through year (or more) of EU legislative process.

The NZIA is a substantial announcement, but at the moment it is more a goal than a support mechanism. Vagneur-Jones identifies a set of challenges that will make reaching the EU’s 40% goal difficult. Some are inherent in the nature of the EU’s fragmented governance, where countries themselves still have a significant say in support mechanisms and planning. The US, in contrast, has coordinated federal tax credits, valid in any domestic location. Others are structural. In particular, the NZIA adheres to World Trade Organization law, a stark contrast to the IRA. WTO adherence complicates efforts to set local content requirements.

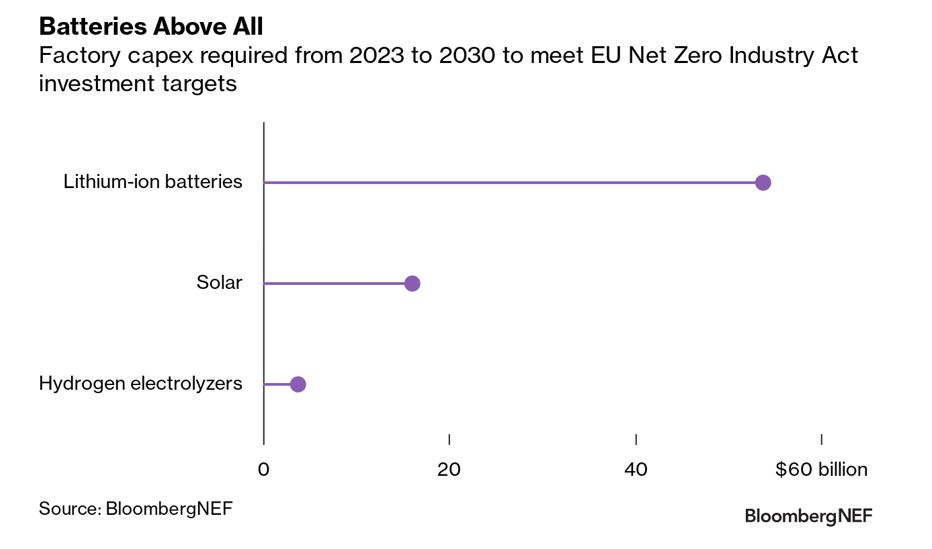

And importantly, meeting the EU’s goals will incur a cost. Meeting 40% of the EU’s demand for batteries, solar, and hydrogen electrolyzers will require more than $70 billion of manufacturing capacity investment between now and 2030, with more than $50 billion of that just in the battery supply chain.

It will also incur additional costs for deployment thanks to structurally higher costs for equipment manufactured in the EU: an additional $12 billion a year for batteries and $3 billion a year for hydrogen electrolyzers.

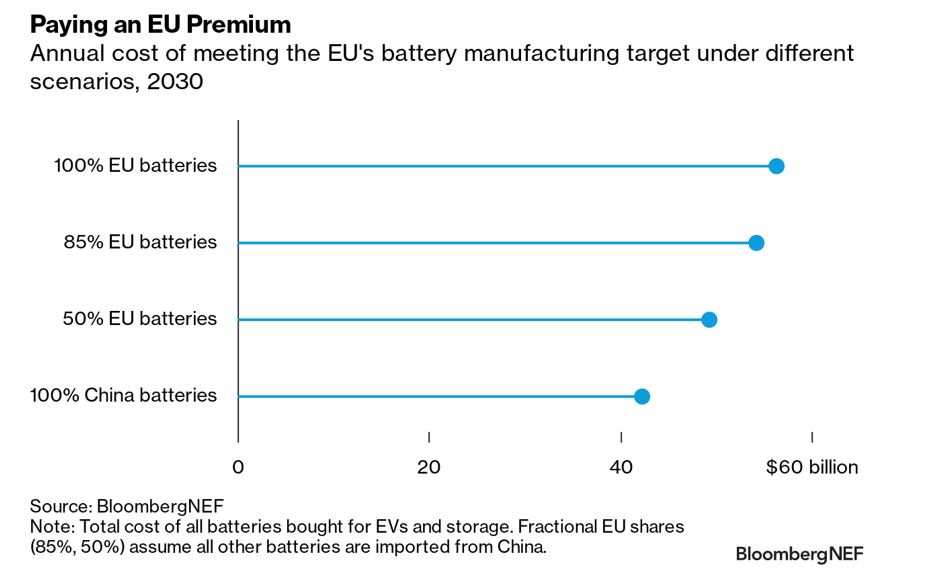

Batteries provide a clear illustration of the opportunity cost in building substantial EU battery manufacturing capability. Today, battery packs made in Europe are 33% more costly than those made in China. Even with the assumption that battery costs decline in line with their historical 17% learning rate, meeting all of EU battery demand with batteries manufactured within its borders would cost an additional $11.9 billion a year in 2030.

That additional cost cannot be wished away. Higher equipment costs also mean a higher cost for stored electricity in stationary applications, and a higher price for automobiles. Those costs will be distributed across millions of vehicle buyers and hundreds of millions of electricity ratepayers, but they will be real.

The major industrial policy moves underway in the US and EU have the potential to remake each country or bloc’s clean technology manufacturing landscape. Already in the US, the IRA’s incentives have brought manufacturing capacity home that would not otherwise be built. The combination of forecast demand and clear and accessible tax credits to support supply are having their effect.

The EU’s moves are still nascent, and they might be more challenged in the future too. The first hurdle is the sheer scale of current importation, for solar in particular. Between January and November 2022, 95% of the EU’s solar module imports came from mainland China. And without the same sort of production-linked credits which the US is deploying, investors may not have sufficient visibility on long-term support to dedicate capital to expansion.

Finally, given the current political climate, the US and EU are unlikely to become clean energy equipment exporting powerhouses anytime soon. With China, East Asia and Southeast Asia all ramping manufacturing, a more realistic goal for Western nations might simply be to meet local demand with local supply. After all, demand is poised to grow massively everywhere. US and EU manufacturers could have plenty to feast on just by eating their own slices of the pie.