Hydrogen and recycling are key technologies to lower the emissions of the world’s most widely used metal

New York and Beijing, December 1, 2021 – Steel production could be made with almost no carbon emissions through $278 billion of extra investment by 2050, according to a new report from research firm BloombergNEF (BNEF). Hydrogen and recycling are likely to play a central role in reducing emissions from steel production. Steel is responsible for around 7% of man-made greenhouse gas emissions every year and is one of the world’s most polluting industries.

Government and corporate net-zero commitments are pushing the steel industry to cancel out its emissions by 2050. Efforts to decarbonize steel production are central to the net-zero aspirations of China, Japan, Korea and the European Union. The report “Decarbonizing Steel: A Net-Zero Pathway”, which was launched in time for the virtual BNEF Summit Shanghai, outlines the path to making profitable, low-emissions steel and describes how a combination of falling hydrogen costs, cheap clean power, and increased recycling could reduce emissions to net zero, even while total output increases.

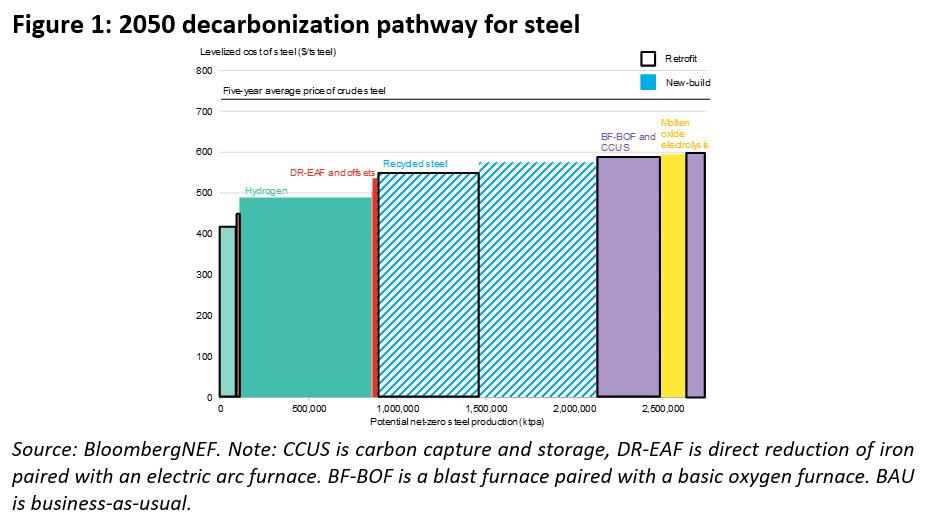

By 2050, green hydrogen could be the cheapest production method for steel and capture 31% of the market. Another 45% could come from recycled material, and the rest from a combination of older, coal-fired plants fitted with carbon capture systems and innovative processes using electricity to refine iron ore into iron and steel. This would be a dramatic shift in the type of furnaces and fuels used to produce steel. Today, around 70% of steel is made in coal-fired blast furnaces, with 25% produced from scrap in electric furnaces, and 5% made in a newer, typically natural gas-fired process known as DRI, or direct reduced iron. Converting a significant portion of the fleet to hydrogen would require more DRI plants and more electric furnaces. Blast furnace production would fall to 18% of capacity in this scenario.

“The steel industry cannot afford to wait for the 2040s to start its transition,” said Julia Attwood, head of sustainable materials at BNEF and lead author of the report. “The next ten years could see a massive expansion of steel capacity to meet demand in growing economies, such as India. Today’s new plants are tomorrow’s retrofits. Commissioning natural gas-fired plants could set producers up to have some of the lowest-cost capacity by retrofitting them to burn hydrogen in the 2030s and 2040s. But continuing to build new coal-fired plants will leave producers with only bad options toward a net-zero future by 2050.”

In order to achieve this transformation, there are five key actions for the sector to consider: boost the amount of steel that is recycled, particularly in China; procure clean energy for electric furnaces; design all new capacity to be hydrogen or carbon capture-ready; begin blending hydrogen in existing coal- and gas-based plants to lower the cost of green hydrogen; and retrofit or close any remaining coal-fired capacity by 2050.

Producing green steel from hydrogen and electric furnaces will require massive amounts of clean energy, and a shift to higher grades of iron ore. This could change where most steel is made, or shake up the mining industry. Russia and Brazil both have access to high-quality iron ore reserves and to abundant clean power. Moreover, Brazil is expected to have one of the lowest costs for hydrogen production by 2030, according to research by BloombergNEF. South Africa and India have good iron ore reserves and the potential to produce a large amount of low-cost clean power. The world’s largest iron ore producer, Australia, however, currently produces lower grade ores, and could lose its number one place in the supply chain, if it does not invest in equipment to upgrade its product.

China will continue to play a pivotal role. Currently home to 57% of the world’s steelmaking capacity, its path to lower emissions will set the direction for the industry as a whole. The Chinese steel industry intends to focus first on increasing recycling and energy efficiency before adopting early-stage technologies like hydrogen and carbon capture.

Kobad Bhavnagri, head of industrial decarbonization at BNEF said: “The global steel industry is poised to begin a titanic pivot from coal to hydrogen. Green hydrogen is both the cheapest and most practical way to make green steel, once recycling levels are ramped up. This transition will cause both great disruption, and great opportunity. Companies and investors don’t yet appreciate the scale of the changes ahead.”

The support that policymakers provide for industrial decarbonization could also be a deciding factor for steelmakers. Subsidies for key enabling technologies, such as the hydrogen and carbon capture tax credits in the U.S.’s pending Build Back Better Bill, green steel procurement mandates for the public sector, like the Industrial Deep Decarbonization Initiative announced at COP26, or rising carbon prices, like those in the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme, could all help green steel to compete with fossil-fuel based production.

BloombergNEF estimates that new clean capacity and retrofits for lower emissions will cost the steel industry an additional $278 billion compared to business-as-usual capacity growth. This is a relatively modest figure, compared to the $172 trillion estimated by BNEF to decarbonize the global energy sector. Most of the costs to make green steel come from operations, rather than capital costs. Reducing the cost of green hydrogen is thus critical, and BNEF estimates that these should fall more than 80% by 2050 to under $1/kg in most parts of the world. Green recycling is also a cost-effective and immediate solution. Steel recycled using 100% clean electricity would only require a 5% premium to match costs for today’s recycled material. By 2050, with lower clean power costs, this premium could shrink to less than 1%.

Contact

Veronika Henze

BloombergNEF

+1-646-324-1596

vhenze@bloomberg.net