Written by Bhuma Shrivastava. This article first appeared in Bloomberg News.

India’s power companies have a problem largely responsible for $10 billion a year in losses. Slum dwellers steal electricity and refuse to pay their bills. But company officials often can’t go in without being chased by mobs—and sometimes beaten, tied up, urinated on, even murdered.

So officials at Tata Power Co.’s joint venture with the Delhi state government came up with a solution that’s turning out to be a model, not just for the rest of India, but for the world: It hired women living in the 223 slums it serves in the northern and northwest parts of the capital and called them “Abhas,” from the Sanskrit word for light.

Tata Power Delhi Distribution Ltd.’s force of now 841 wives, mothers, and women as young as 20 go around the slums, knocking on neighbors’ doors and persuading, coaxing, cajoling and nagging them to pay their power bills.

Bill collectors, known as Abhas, conduct a meeting outside a house in a New Delhi slum.

Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg

The result is a 183 percent increase in revenue over five years from the slums where Tata operates the project, with minimal cost to the company. Active power connections have risen 40 percent to 196,000—meaning that 56,000 previously freeloading homes have become active, bill-paying power customers.

“This gave us a way to get into these neighborhoods, rife with mafia and political influences,” said Praveer Sinha, chief executive officer and managing director at Tata Power-DDL, which had started out operating literacy campaigns for slum women in 2010 as a way into the communities. “We thought educated women would give us a much better buy-in.’’

Praveer Sinha

Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg

The success of Tata Power-DDL’s initiative is inspiring imitation. Rival BSES Delhi, co-owned by the Delhi state government and Anil Ambani-controlled Reliance Infrastructure Ltd., engaged 40 women earlier this year in a pilot project in a west Delhi slum. Having resident women distribute bills and collect payment from neighbors produced “very encouraging results” that will now be used to expand the program, according to BSES spokesman Deepak Shankar.

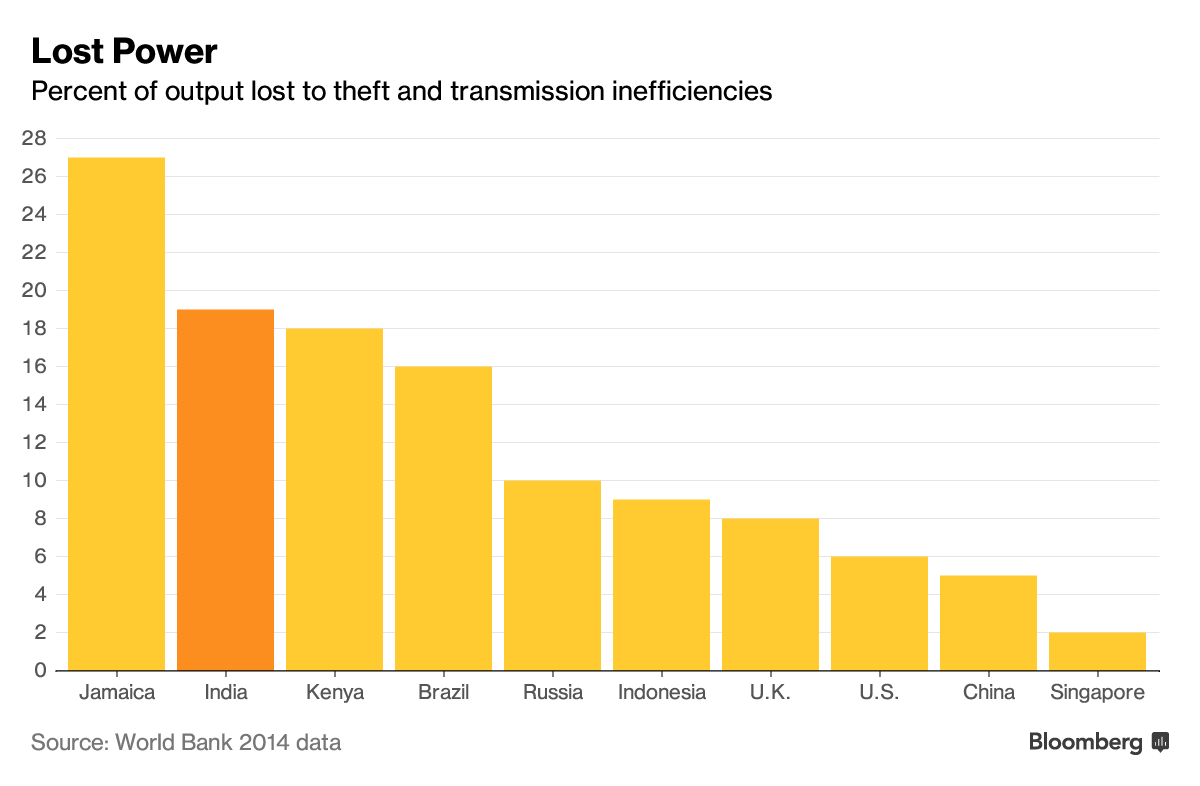

The World Bank is trying out similar initiatives in Jamaica and Kenya, and is considering adapting it to other African countries. So far, Kenya Power & Lighting Co. has improved connection rates by doing more community engagement based on the Tata model that “has provided a lot of learning, which we are incorporating,” Sunita Chikkatur Dubey, a Ghana-based World Bank consultant, said via email.

The slum in north Delhi known as Sanjay Basti, home to 4,000 people just 2 miles (3 kilometers) away from Tata Power-DDL headquarters, was once notorious for harassing power inspectors. Residents would threaten to pull away ladders when company officials climbed electricity poles to disconnect illegal hookups, said Amarjeet Kaur, who used to be an illiterate housewife before she was hired as an Abha in 2013.

“Residents would ask me: ‘Why did you become a ‘company person’ when you are one of us?’” said Kaur, 39, as she walked through the slum’s serpentine lanes filled with low-slung electricity cables that these days connect to almost all the brightly painted brick dwellings. “Now, women are in a queue to take up this job. Even the boys want to become Abhas.”

Abhas, whose numbers are expected to swell to 1,000 by next year, do more than just hand-deliver electricity bills and collect payments. They advise slum dwellers on power conservation and safe practices: Use LED bulbs, don’t use old motors to pump underground water or it will spike your electricity bill, and most importantly, don’t use power cables as clotheslines. The Abhas’ newest mandate, Tata Power-DDL’s Sinha says, is to encourage slum residents to make mobile payments, which reduces the need to handle and safeguard large amounts of cash.

Abhas make about 4,000 rupees ($60) a month on average, which is what some part-time domestic helpers can make. It includes a base salary plus extra pay based on securing full bill payment, partial payment or new meter installation. Abha managers, 25 in total, can make as much as 12,000 rupees a month—about the equivalent of a bus or van driver in Delhi.

Amarjeet Kaur, left, and another bill collector with a customer in the Sanjay Basti slum.

Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg

Residents say they prefer dealing with women from their own communities—who personally deliver bills when they know neighbors are home and accept partial payment when money is tight—rather than outsiders. If their repeated cajoling and nagging doesn’t result in payment, then power is disconnected. The Abhas have the support of the community leaders, known as pradhans, who weigh in if needed.

“Earlier if we weren’t home when the company official came to deliver the bill, we’d miss paying and become defaulters,” said Usha, 38, who goes by one name and lives in a 90-square-foot room with six other family members. She likes the convenience of dealing with people she knows, and laughs off any questions about feeling nagged. “If we consume electricity, we’re supposed to pay for it!”

The scarcity of resources in slums ensures an interdependence among residents that means they’re more likely to listen to one of their own, said Purnima Singh, a psychology professor at the Indian Institute of Technology in New Delhi.

“The social fabric is much tighter in slum clusters,” said Singh. “An outsider will never match up in having this level of influence.”

Tata Power-DDL started zeroing in on slums in 2009, considering them the last hurdle to paring losses. India’s power companies lose revenue on about a fifth of the electricity they supply, or about $10.2 billion annually, due to problems including theft, meter tampering, billing issues and leakage due to faulty equipment, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers India estimates.

To thaw the hostility that Tata Power-DDL officials were encountering, it set up a special consumer group to start drug rehabilitation, provide medical vans, install drinking water stations and launch the women’s literacy program. The idea to hire women surfaced in 2012 when, Sinha said, the women who had been studying to read and write started asking how to put their education to use.

“These women weren’t allowed to go out and work by their families,” said Manisha Wadhwa who now heads the group. “But they could always work in their own communities, choose their own hours and still give us better reach in their neighborhoods.”

Wadhwa’s group is still trying to tame 39 slums Tata Power-DDL serves that remain crime-prone and mafia-ridden, where the few Abhas the company has been able to hire haven’t made much headway.

People pelt stones and pour hot water from the roofs” in one of the areas, Wadhwa said. “We are still trying to befriend them.”

A group of bill collectors in Sanjay Basti.

Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg

Still Tata Power-DDL has come a long way from the days before 2012 when officials had to remove their badges to keep from being identified when visiting slums. Now women like Kaur insist on having Tata Power identity cards, as it gives them status.

“We have learned from this initiative that we can work closely with communities to improve economic outcomes,” said Sinha. “We don’t need to do charity.’’

—With Rajesh Kumar Singh and Adrian Leung.