By Bryony Collins, Bloomberg NEF. This interview first appeared on the Bloomberg Terminal.

Everledger Ltd wants to use its experience determining the provenance of diamonds to improve the sustainability of the global supply chain for electric vehicle batteries.

The London-based company has built a digital ledger platform containing details of more than 2 million diamonds worldwide, which is used by manufacturers and retailers to ascertain the origin of certified gemstones. Everledger is developing a similar construct to track and trace the lifespan of lithium-ion batteries, from manufacturer to dealership to scrapyard, in order to assign each battery a unique thumb print that can speed up the recycling or refurbishment process.

“Our aim is to track the life cycle of batteries, extend their lifetime and make sure that we don’t lose metals and minerals to landfill,” said Lauren Roman, responsible for metals and minerals blockchain supply chain solutions at Everledger. It costs on average $1,000 to recycle a lithium-ion battery, whereas batteries re-purposed as stationary energy storage can command $5,000 on the market, so there is incentive to re-purpose or refurbish batteries instead of recycling them, Roman told BNEF in an interview.

Everledger’s blockchain assigns each battery a record of its history so that refurbishers and recyclers can more easily determine whether it is appropriate for end-of-life energy storage. This will increase the proportion of batteries able to be refurbished, said Roman.

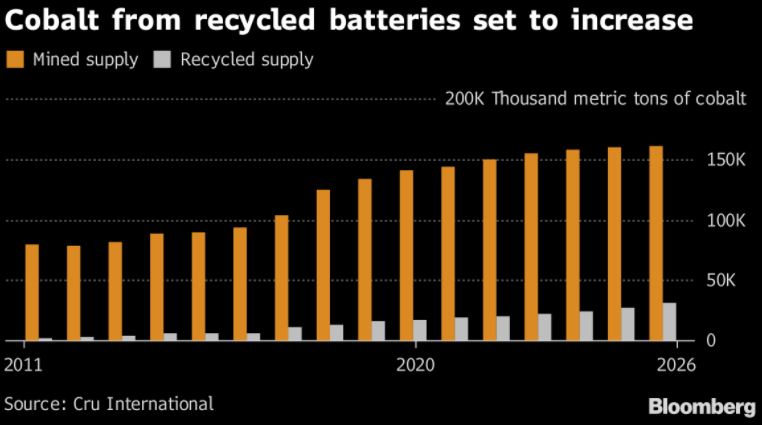

It can also speed up the recycling process because battery manufacturers can put disassembly instructions on the Everledger blockchain that are useful to a recycler, said Roman. This helps to reduce the amount of battery components, such as aluminum, copper, lithium and cobalt, going to landfill, she added. It could also reduce pressure on battery manufacturers to source enough lithium and cobalt to meet rising battery demand.

Automakers such as Volkswagen and Audi, and battery manufacturers Johnson Controls and Saft Batteries, are among companies that have committed to adopting the Everledger blockchain to track electric vehicle batteries. Everledger is working with the Global Battery Alliance to scale up the use of digital ledgers to track battery provenance from now to 2020.

Leanne Kemp, chief executive and founder of Everledger, and Lauren Roman spoke to BNEF in a telephone interview on August 30 about developing a blockchain for the lithium-ion battery supply chain.

BNEF: What is Everledger’s background?

Kemp: Everledger began in April 2015 when we recognized that a set of emerging technologies would be able to provide a platform of provenance. In other words, the ability to track and trace objects from origin to the end state of use, and then reuse.

We began tracing diamonds from the mine to the retail outlet. We now have over 2.2 million diamonds on the Everledger platform and 7 operational centers.

Everledger raised a Series A round in March 2018 for $10.4 million. We’re backed by Fidelity Investments, Bloomberg Beta, and Japan-based Rakuten Capital. And we’ve been generating revenue since the company started from our work in the diamond industry.

We work with a range of diamond industry leaders including Chow Tai Fook – a major retailer, the Gemological Institute of America – a leading certification house, Hari Krishna – a diamond manufacturer, and other mining companies.

In early 2017 we started working with the World Economic Forum which formed the Global Battery Alliance. This is a public – private partnership, which brings together leading businesses along the battery value chain with public and civil society, to catalyze and accelerate action for the sustainable global supply chains of batteries.

Q: How do you ascertain that a diamond correctly links to its footprint on the digital ledger?

Kemp: Each diamond in the world is unique and we use material science and scanning technologies like spectrography, HD photography, resonant ultrasound and light refraction to create unique thumb-prints of that diamond.

Some companies in the industry have used such technology for some time, but no one had actually written the connective tissue or built the data highway to connect it together.

Q: What proportion of the world’s diamonds will the Everledger platform account for?

Kemp: By end-2019 about 10 percent of the entire, global trade of certified diamonds will be on the Everledger platform.

Q: How would Everledger technology be adapted to the battery space?

Roman: Our aim is to track the life cycle of batteries, extend their lifespan and make sure that we don’t lose metals and minerals to landfill. Once we have that platform running, we will use material identification technologies to track that material all the way back to the mine.

Between 60 and 70 percent of all the cobalt in the world comes from the DRC, where there are major conflict zone issues, slave labor and child labor – a lot of similar issues that we had with conflict diamonds, which is what motivated Everledger to validate the diamond supply chain. [So if we can find a way to materially identify the origin of battery metals like cobalt and lithium, then our blockchain will improve the traceability and accountability of materials from these conflict-ridden areas].

Traceability of metals like lithium and cobalt is difficult since they are transformed along the supply chain. Technologies continue to emerge, however, that make this increasingly possible. The only real way to track them uniquely through their entirety is with mass balance weight. Other types of identification won’t work for saying a certain parcel or lot number is unique.

At the moment, our blockchain will start with the battery manufacturer; to the vehicle manufacturer; to the dealership; to the scrapyards and recyclers, and companies re-purposing car batteries as stationary energy storage. We’ll probably use auto-identification technologies for tracking batteries throughout their life cycle. Such as radio frequency identification and near-field communication.

There is opportunity in refurbishing batteries for reuse, so they can be used longer for what they were originally built for. Or re-purposing for energy storage – for applications like data centers and home solar energy and other renewable energy storage.

Q: Who would be your clients in the supply chain?

Roman: Audi and Volkswagen are both in the Global Battery Alliance, as are EV battery manufacturers Johnson Controls and Saft. We’re growing that group – adding recyclers, manufacturers and EV [makers] to get a broader perspective.

Regarding who would be Everledger’s customer, paying for battery certification on our blockchain – there are opportunities in lots of spots along the supply chain, but it is most likely going to be the battery manufacturer or the EV manufacturer. In some countries, the vehicle manufacturer may hold producer responsibility for the batteries that are in their vehicles throughout their life cycle.

Europe is revising its Battery Directive and some countries are looking at producer responsibility schemes for EV batteries.

It costs about $1,000 on average to recycle a lithium-ion EV battery right now, excluding shipping and handling fees.

If that battery can be refurbished to be used in an older vehicle, or re-purposed for energy storage – those batteries can be sold for an average of $5,000 apiece. So rather than spending $1,000, you can make $5,000 – so that’s huge motivation.

Q: Could you reduce battery recycling costs using blockchain technology?

Roman: The biggest challenge that refurbishers and ’re-purposers’ have is that if they don’t know the history of a battery, then they sometimes have to assume that it is not a candidate for refurbishment.

Our platform identifies a battery at the time it was manufactured and records what car it went into; who sold it; which garages maintained it and what they did to it – because all these players can interact with the blockchain. By the time it gets to a refurbisher or recycler, they can scan that tag and know right away if the battery is a candidate for refurbishment or re-purposing.

So by using our blockchain, a refurbisher can increase the proportion of batteries it is able to refurbish or re-purpose.

Q: Can you see the blockchain reducing cost?

Roman: The original battery manufacturer can put safety and disassembly instructions on the blockchain so that when the recycler gets that battery, the blockchain can speed up the recycling process. [This is] because they don’t have to do extensive record searches or diagnostics and they have the information to hand. Likewise, the blockchain can inform a recycler if a battery is good enough to be refurbished rather than recycled.

Kemp: It’s not just about only doing things cheaper. Blockchain will improve the traceability and sustainability of materials – to support environmentally and socially responsible sourcing. It’s also about how can we avoid landfill for a more livable planet – it pays in other ways to bring this back into the circular economy, even if it doesn’t make the process cheaper straight away.

Q: At what stage are you of implementing this technology in the real world?

Kemp: There is an implementation track set down by the GBA [Government Blockchain Association] between now and 2020. In 2018 we’re building proof-of-concept through public launches with seed funding commitment and governance approval.

By September to January, we will begin to understand the capacity for action and then have it in the hands of industry.