This article first appeared on Bloomberg View and the Bloomberg Terminal.

Toward the end of Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s testimony before Congress last month, U.S. Senator Brian Schatz asked him, “Do you agree that climate change creates financial risks for the individual financial institutions and for our financial system as a whole?” His answer reveals the challenge in finding a long-term, universal answer to business as usual. It also raises questions: What kind of risk does climate change represent, and what will companies do about it?

Powell’s response suggests that while the Fed isn’t doing nothing about climate change, it isn’t doing much, either:

We don’t formally or directly include climate change in our supervision, but we do actually require financial institutions, particularly those who are more exposed to natural disasters and that kind of thing — we do require them to understand and manage that particular operating risk. So, for example, if you’re a bank in — you know, on the southern coast of Florida and you’re subject to hurricanes, we definitely require you have plans and risk-management things in place to deal with that sort of thing. So you would pick up natural disasters and that kind of thing, which are associated with climate change.

Schatz, who wrote to Powell last month about climate-related risks to the U.S. financial system, pressed a bit:

I get that you’re supposed to pick up any risks related to natural disasters. The question is whether you really loaded in the latest information from the scientific community, to go back to these banks, to go back to REITs, to go back to lenders who have either stranded assets or assets in the coastal area, or who’s the supply chain is particularly dependent on a certain kind of weather pattern which is not materializing anymore. Do you think you’re doing enough in this space? Or let me phrase it another way: Are you confident that you’re doing enough in the space?

“I think we’re open and we’re clear-eyed about the nature of coastal risks and natural-disaster risks and that kind of thing,” Powell replied.

To the Fed, climate change is already manifest, and a risk. But it’s an operational risk, not a systemic one. It’s not a surprising answer, and it also shows little response to central banking’s biggest climate-change problem, which Governor Mark Carney of the Bank of England called in 2015 “the tragedy of the horizon”:

We don’t need an army of actuaries to tell us that the catastrophic impacts of climate change will be felt beyond the traditional horizons of most actors — imposing a cost on future generations that the current generation has no direct incentive to fix.

That means beyond:

• the business cycle;

• the political cycle; and

• the horizon of technocratic authorities, like central banks, who are bound by their mandates.

The horizon for monetary policy extends out to 2-3 years. For financial stability it is a bit longer, but typically only to the outer boundaries of the credit cycle — about a decade. In other words, once climate change becomes a defining issue for financial stability, it may already be too late.

Powell’s remarks — especially with the perspective of the four years since Carney’s delineation of the problem — inspired me to look at what the private sector, including financial institutions, is doing about climate change. Companies aren’t technocracies, much as they might pride themselves on technical capability and analytical thinking. They also have more imminent horizons than central bankers; does that mean climate change is more or less of an issue in the private sector than it is for Powell and his colleagues?

Rather than parse the private sector’s words, I counted them.

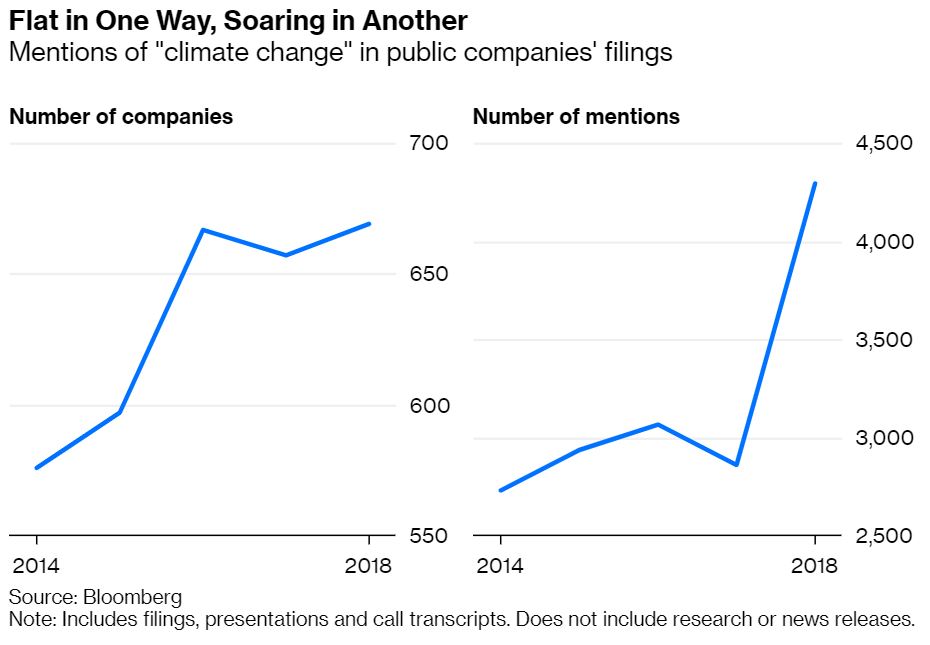

Using the Bloomberg Professional Service’s Document Search function, I created a list of every public company that mentioned climate change in their filings for 2014 to 2018. The number of companies hasn’t changed hugely — to 669, up 16 percent from 575 — but total mentions have increased more than 50 percent, to 4,496 from 2,729.

But what do these companies actually say during their management calls? “Climate change” as a marketing buzzword is one thing; a mention in transcripts, given scarce time and questions from analysts, is more significant.

But what do these companies actually say during their management calls? “Climate change” as a marketing buzzword is one thing; a mention in transcripts, given scarce time and questions from analysts, is more significant.

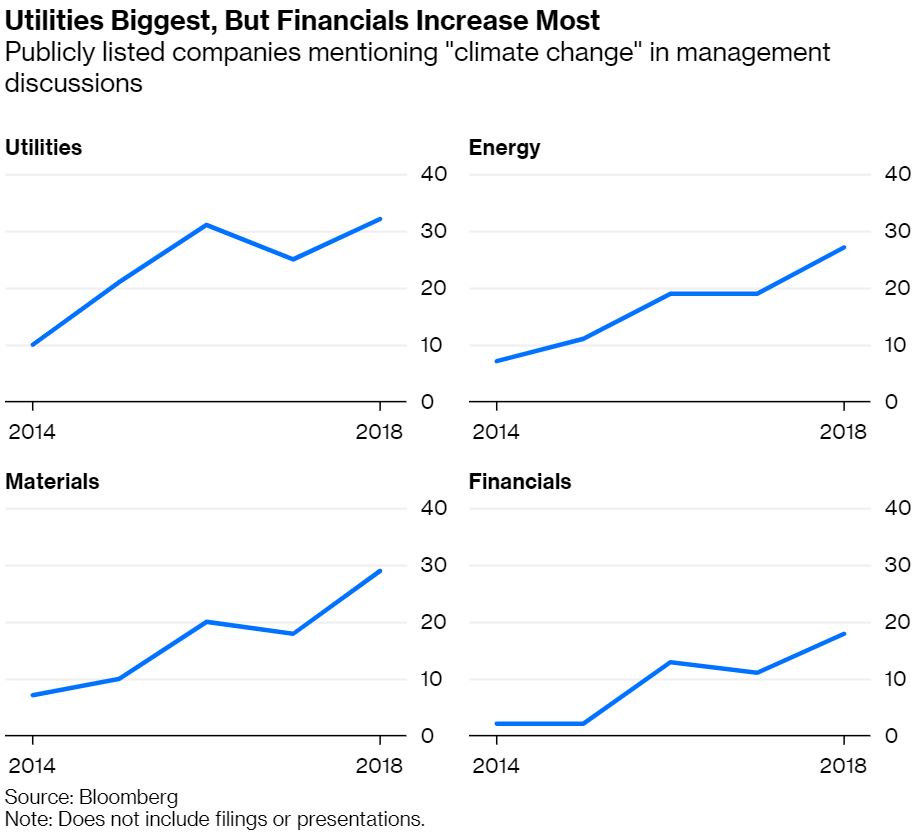

Utilities, energy and materials companies mentioned climate change the most. Every sector has seen a significant increase since 2014 in the number of managers talking about climate change. I included financial companies here as well:

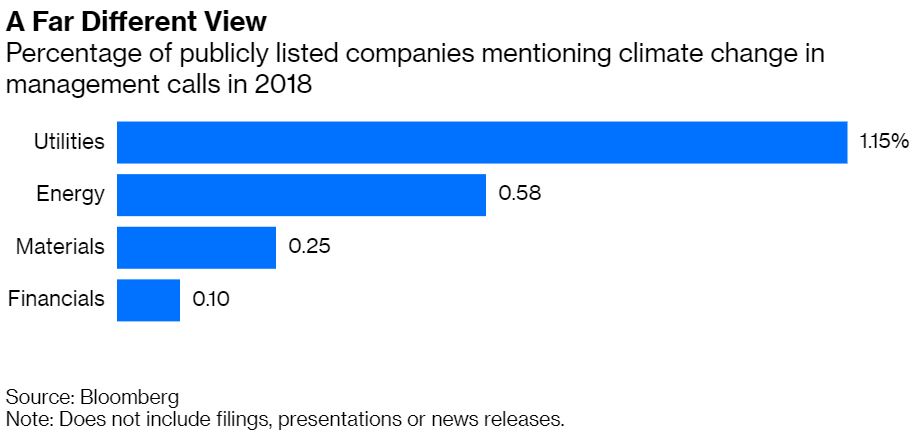

Financial companies’ mentions actually increased the most, in terms of managers noting climate change on calls (18, up from two). That trend tells us something, but what about the percentage of companies in each sector mentioning climate change? There, financial institutions look less impressive:

Financial companies’ mentions actually increased the most, in terms of managers noting climate change on calls (18, up from two). That trend tells us something, but what about the percentage of companies in each sector mentioning climate change? There, financial institutions look less impressive:

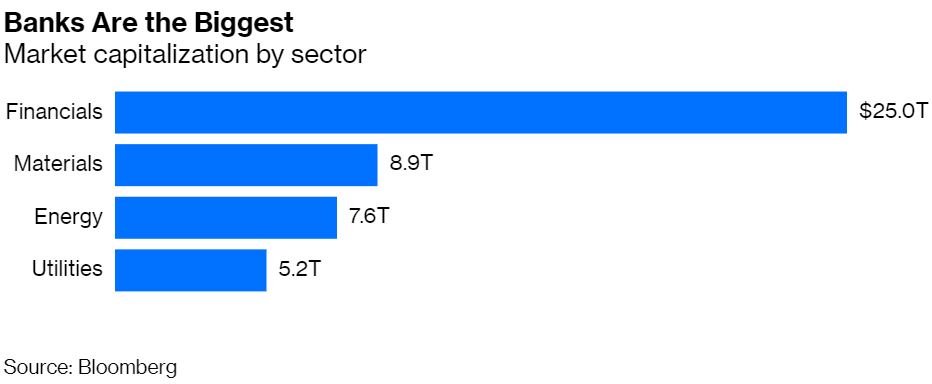

Even in obviously climate-change-exposed industries such as utilities, barely more than 1 percent of company managers mentioned climate change in their discussions with analysts. Only a tenth of a percent of financial-company management teams mentioned it last year. Financials are also a bigger sector (in terms of market cap) than materials, energy and utilities companies combined.

That’s not to say that climate-change risks aren’t already operational risks, to borrow Powell’s phrase. A First Street Foundation report published last month found that increased tidal flooding caused by sea-level rise has already eroded $15.8 billion in relative home value on the U.S.’s Eastern Seaboard. And the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis also noted that every two weeks, a financial institution announces new restrictions on funding the coal sector.

An operational risk across a large portfolio, though, is not as significant as what PG&E Corp. has experienced from climate change. It’s not as significant as mining company Rio Tinto Group says, in its first-ever climate-change report informed by the recommendations from the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures: “We recognize that it is largely caused by human activities and has the potential for a lasting, negative impact on our business, our communities and the world.”

In a speech last November, Benoit Coeure of the European Central Bank gave a speech titled “Monetary Policy and Climate Change” in which he said that “the horizon at which climate change impacts the economy has shortened, warranting a discussion on how it affects the conduct of monetary policy.” Coeure’s view is that Carney’s distant horizon has collapsed into a central banker’s time frame. In that time frame, it’s also more than an operational risk for individual institutions. It’s an operational risk for central banks, and as go their monetary policies, so goes the economy. Climate change is a risk. As to what kind of risk it is, and to whom, and in what ways, you can listen to what companies say. Or you can ask your central banker.