Industrial decarbonization will require massive amounts of capital investment over the next 30 years. Decarbonizing steel alone will require $278 billion in additional capital, according to BloombergNEF. While the costs and risks of net-zero technologies are high for now, venture capitalists (VCs) believe there are significant returns to be made for first movers.

Institutional investors and asset managers are however taking a more reserved stance. They are in favor of playing a part in the net-zero transition, as long as returns look like what they would get under a business-as-usual scenario. Given that most decarbonization projects are early stage, this is unrealistic in the short-term. The heavy lift of financing industrial decarbonization will likely be left to venture capitalists, impact investing, governments and companies themselves.

No time to wait

At the BNEF Summit New York, The Engine’s Katie Rae said most venture capitalists want to see evidence of customer adoption for a technology before investing. However, the urgency of decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors means there is no time to wait. The group looks for technologies that can deliver “step-function changes”, and are three to five years away from true pilot production.

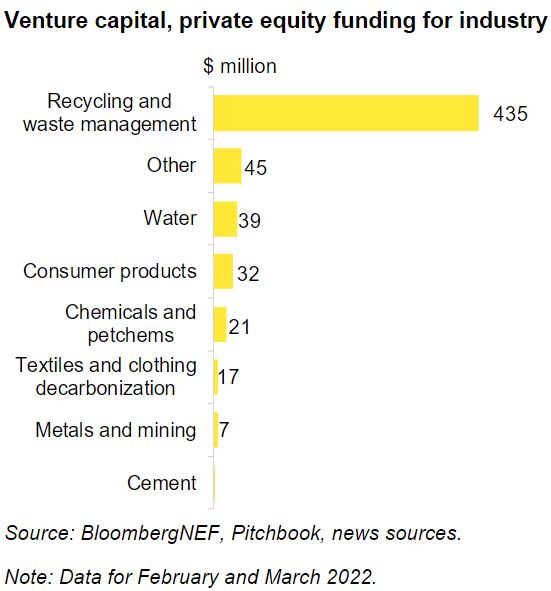

Hardware has a reputation for only delivering small returns on long timescales. Rae pointed out that industrial production is an enormous market where VCs can make returns, and at huge multiples. Investors need to understand the nuances of the technology and become comfortable with the risks. There are people in the investment community who can do this, but it will most likely remain a specialized skill and a niche target. Even within venture capital, large amounts of funding is flowing to the more established sectors of recycling and circularity for plastics, metals and packaging, rather than emerging solutions to decarbonize primary materials production.

VCs need to help startups build a community

Industrial partnerships are often seen as a seal of approval for early-stage technology startups, and VCs can play a key role in delivering these for their portfolio companies. Andree-Lise Methot from Cycle Capital said that “success comes from the equation you build around a company” and talked about how the group works to find industrial partners who can write large checks and deliver a route to market for their startups. This allows venture capitalists to finance the company, while institutional or corporate investors finance the plants.

Companies have some creative options in green finance

Industrial companies have ambitious spending plans for their net-zero goals. ING’s Daniel Shurey pointed out that there was already $50 billion of sustainable debt finance in the chemicals space, and Dow Chemical alone was planning to spend $1 billion every year to meet its 2030 climate target. There is clearly a huge need for finance, but traditional mechanisms are not suited to this new challenge.

There are three major issues with applying traditional green finance to industrial decarbonization, according to Shurey:

- Decarbonization cannot be assigned to only one project, or asset. The whole system of production often needs to change

- The risk profile of these pilot plants or early-stage technologies does not match what institutional investors are looking for

- A whole-of-company approach is needed. Financing one or two projects does not represent an organization’s “ESG journey” properly

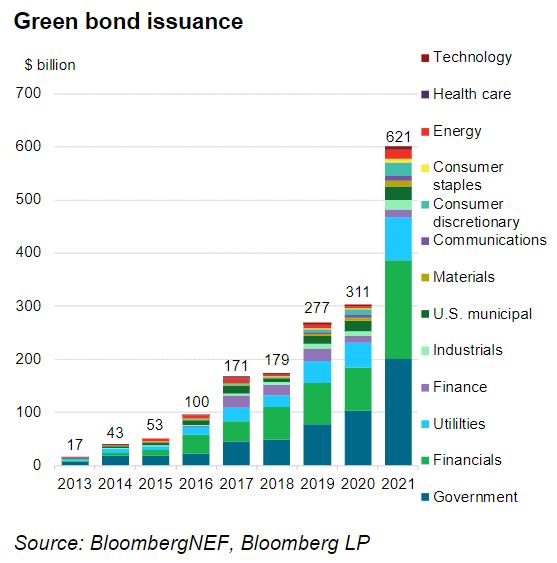

Green finance is already adapting to meet the needs of heavy emitters. Companies can adopt a portfolio method, where an inventory of the organization’s ‘green’ assets and spending is used to create a cap for green bond issuance. Or they can take an integrated approach, and combine use of proceeds mechanisms with sustainability-linked debt to finance their net-zero projects.

Shurey noted that a side benefit of sustainability-linked debt is that it can be seen as a road map for a company’s carbon abatement plan.

Investors are not interested in funding high-risk technologies and projects

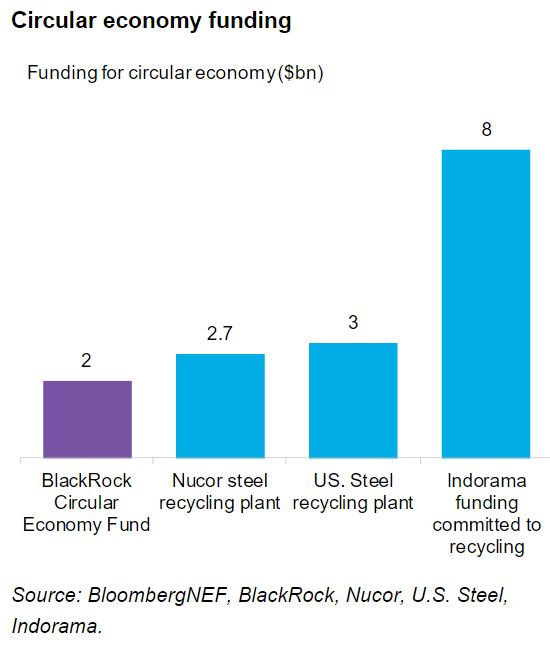

Evidence of technology maturity and effective de-risking are prerequisites for institutional investors to put money into industrial decarbonization. One example of this is companies breaking out their ‘clean’ units into separate companies. This has been commonplace in utilities and is now spreading to the automotive and industrial sectors. BlackRock has launched Decarbonization Partners, a JV with Temasek, to help scale innovative climate-tech, but only once the tech has been de-risked and the startup is revenue-generating.

In practice, this means that for the next decade large investors will leave the financing to governments and VCs, as they have traditionally done.

Profits are non-negotiable and inflationary pressures are inevitable

BlackRock’s Paul Bodnar said that the asset managers’ clients wanted “exposure to the climate-tech of the future” but stressed that cost premiums for net-zero technologies had to come down for investors to remain confident in carbon-intensive sectors. He offered an upbeat view, citing cost declines in other industries, such as electric vehicles and batteries, had been faster than expected. However, they are not interested in “crowdfunding” industrial decarbonization, and will not be a major player in the near term until net-zero production methods are competitive with unabated production. Maintaining current levels of returns will require companies to either charge green premiums to protect their margins or for governments to introduce CO2-pricing mechanisms that increase costs for net-zero laggards. Either option will increase production costs for entire sectors, resulting in price increases throughout the industrial supply chain – which may or may not be transitional.