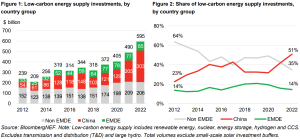

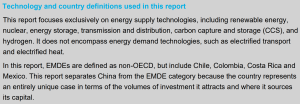

In 2022, some 75% of new power generation capacity added in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), excluding China[1], was low-carbon. Energy transition investment in these markets reached a new record of $85 billion, up 10% from 2021. However, low-carbon investment in and to EMDEs continues to fall significantly short of what is required to meet net-zero emissions goals by 2050. Investments in fossil fuel energy supply[2] still eclipse those in clean energy and the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that annual investment in low-carbon energy supply must grow more than five-fold from 2022 to 2030. The disparity in clean energy investment between emerging economies and richer nations persists, with EMDEs comprising less than 15% of global investment.

The full report is publicly available here.

However, there are positive developments, primarily in markets with robust enabling environments. Brazil stands out this year and for most of the last decade. With an effective and stable clean energy policy framework and strong, supportive and independent public institutions, the country represented over one-third of EMDE renewable energy investment in 2022, contributing significantly to the EMDEs’ total new record. India and South Africa follow Brazil as the top three main investment destinations in 2022. Most other economies, however, continue to attract insufficient low-carbon energy investment.

The lessons learned from countries across all income groups that have been trailblazing the energy transition highlight that meaningful, stable progress requires strong collaboration between key stakeholders. Governments, national public finance institutions, the private sector, and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) need to work together to create favorable investment environments, mitigate risks, enhance liquidity and deploy catalytic investment effectively. Domestic EMDE financial institutions have been notably effective at supporting the transition in the last five years, and their investment has proven relatively resilient to external shocks like Covid-19 and rising interest rates. There is a clear need and opportunity to develop and harness local capital markets. That said, to reach the scale of finance required for transition, which will require many EMDEs to more than triple their renewable capacity to reach the global 11 terawatts of global capacity needed by 2030, international private capital must also be mobilized at much greater rates. Development finance institutions, bilateral donors and MDBs must all accelerate efforts to mobilize international private finance, particularly through rapidly scaling the availability and accessibility of catalytic instruments like guarantees.

This report provides an overview of the current state of the energy transition and its financing in EMDEs and discusses how to execute and accelerate it. Six country case studies – Argentina, Brazil, Egypt, India, South Africa and Vietnam – are used to explore how different stakeholders can influence macro and microeconomic factors that affect investment in EMDEs. Finally, it discusses four transformative initiatives or developments that could significantly accelerate the transition in EMDEs: the emergence of country platforms as a coordinating mechanism, ongoing efforts to strengthen and evolve MDBs, the scaling of high-integrity voluntary carbon markets, and the development of coal phase-out strategies.

The report’s key findings:

- Low-carbon energy supply investment in EMDEs remains insufficient to reach 1.5C The IEA’s Net Zero Emissions by 2050 scenario (NZE) estimates that a nearly fivefold increase in low-carbon investment is needed by 2030, compared to 2022 levels, while investment in fossil fuel needs to halve.

- Although low-carbon energy supply investment in EMDEs reached a record high in 2022, it still only represents 14% of the global total, the lowest share since 2016. Investment rose by 11% from 2021, reaching $85 billion, with a third of it directed to small-scale solar. Investment remains concentrated in a few markets, primarily in upper-middle income countries. The top 10 markets by investment volume combined account for over 80% of total investment, and Brazil and India together represent more than half of the total.

- Renewable energy represented three-quarters of the new power-generating capacity added in EMDEs in 2022, while fossil fuel’s share fell to a new low. EMDEs installed 94 gigawatts of new capacity, with renewables (including hydro) representing 74% of this. The share of fossil fuels in total capacity added dropped to 26%, down from 48% in 2021.

- While renewables additions and investment remain concentrated in larger EMDEs, technologies like photovoltaics (PV) are rapidly expanding to more markets. In 2022, PV was the primary technology installed in 46% of the EMDEs, up from just 8% in 2012. This is because PV modules cost less than a third of what they cost in 2012, and a sixteenth of what they cost in 2008.

- The results of measures taken in the countries studied in this report highlight the need for unprecedented collaboration among domestic and international stakeholders to achieve net-zero goals within the time frame envisioned by the Paris Agreement, with an emphasis on both strengthening the enabling environment and ensuring public capital is used catalytically to leverage private investment.

- Argentina’s experience demonstrates how a mix of well-designed policy frameworks and financial risk mitigation mechanisms can spur renewable energy development in a challenging macroeconomic context. A combination of auctions and guarantees managed to create bankable projects despite a volatile economic environment. This required an innovative mechanism based on a collaborative approach between the market operator, the national government and the World Bank.

- Brazil’s success illustrates the resilience that a complete and stable policy framework, supported by strong independent public institutions, can bring to the transition of a country. Brazil has one of the most inviting renewable energy enabling environments among EMDEs, which helped drive over $93 billion in investment in the country over 2012-2022. The Brazilian National Development Bank (BNDES) was pivotal to the development of the sector and ensuring low cost of debt for clean energy projects, while the country’s independent Central Bank has been key to maintaining macroeconomic stability.

- Egypt’s story shows the impact of MDB technical and financial support on renewable energy investment flows. One of the main drivers of investment in energy transition in the country was the collaboration of the Egyptian government with MDBs. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) helped the government design a set of power purchase agreements and other incentives offered to developers through a competitive mechanism. In parallel, the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency of the World Bank (MIGA) provided guarantees for projects under the program. This helped drive $3.3 billion in 2017, up from nearly nothing in 2015.

- India’s vibrant clean energy sector highlights how high ambition can be matched to a comprehensive set of policy tools designed to address challenges and mobilize domestic investors in support of the transition. The country has implemented a variety of mechanisms to boost confidence among local financial institutions, leading to a significant growth in local investment. Domestic investment in low-carbon energy was four times higher than foreign investment in 2022. The country has been a role model in holding renewable auctions with high volumes and a regular schedule, with an average of 15GW of renewables capacity auctioned in each of the last five fiscal years.

- South Africa’s challenges illustrate the importance of policy stability, the need for multi-stakeholder collaboration, and the role renewables can play in improving energy security. Despite being a mature renewables market in terms of procurement experience and financing capacity, South Africa faces major energy transition stumbling blocks in its policy instability, regulatory tightness and political risk. When executed properly, its clean power incentives, such as auctions, have driven substantial investment and build, but retroactive changes and cancellations have damaged investor confidence. However, recent changes in regulation have unlocked the potential of distributed PV in addressing power shortages.

- Vietnam’s ambitious clean energy policies show how quickly a vibrant market for renewables can materialize under the right conditions, but also how quickly it can be saturated in the absence of a more holistic energy transition plan. Generous feed-in tariffs triggered a solar and wind boom, driving $44 billion in investment in just four years. However, unsustainable tariff levels, lack of clarity and infrastructure bottlenecks led to a steep decline in investment flows, emphasizing the importance of sustained and clear policy direction.

- The above case studies provide clear examples of how each stakeholder group across the public and private sector has a critical role in driving progress. Crucially, each stakeholder’s action is more effective when working in collaboration across the public and private sector to create vibrant renewables markets, scale up clean technologies or effectively manage the phase-out of fossil fuel assets.

- Governments are responsible for translating their climate targets into a set of policies and regulations that, along with macroeconomic and political stability, create an enabling environment that is conducive to investment, providing stability to investors and carefully deploying limited budget resources where they are most needed.

- MDBs must act as enablers, providing both technical and financial support to host countries, private-sector companies and financial institutions, and project developers. MDBs have a unique role in the interface between governments and the private sector, identifying opportunities where a country can spur investment most efficiently by mobilizing private finance, and where more enabling investment using public resources is needed.

- Where the enabling conditions are in place, the private sector needs to play its role as a creator, financier and operator of the assets that are needed to decarbonize economies.

- These lessons are particularly important as leaders build momentum to triple global installed renewable energy capacity by 2030, from a 2022 baseline. This goal equates to 11 terawatts of renewables capacity by 2030, but contributions will differ around the world. While for earlier adopters of renewables, tripling is the right goal, other countries – especially EMDEs in south and southeast Asia, the Middle East and Africa – will need to set a steeper path away from fossil fuels while meeting growing electricity demand.

- Some transformational initiatives also have the potential to accelerate the transition by ensuring appropriate multi-stakeholder collaboration, increasing and diversifying investment flows and creating new strategies for remaining challenges. These include evolution of the mandate of MDBs to focus on climate and private-sector mobilization, leveraging country platform approaches, developing managed coal phase-out solutions and enhancing voluntary carbon markets.

- An evolution of MDBs to increase their support for the energy transition and identify opportunities to mobilize the private sector as a developer of assets and investor is critical to driving capital to EMDEs and achieving global climate targets. This is fundamental, as MDBs are uniquely positioned to act as a key enabler to support governments on how to create the environment for private capital to flow at scale and tailor the activity based on country-specific challenges. The MDB community has begun to respond to this challenge in recent years, signaling their intentions to increase blended finance activity and collaborate with the private sector, as exemplified by the creation of the World Bank Private Sector Investment Lab.

- Country platforms, such as Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs), are key instruments to ensure the level of cross-stakeholder coordination that is required to accelerate the transition. Country platforms are designed to bring stakeholders together around a comprehensive transition plan and mobilize financing against it, including from the private sector. They set ambitious climate objectives with their execution conditional to technical or financial support from global partners.

- Beyond boosting renewables, a managed phase-out of coal-fired power plants (CFPPs) is one of the most important steps to decarbonize the global economy. While the number of pledges to shut down coal plants has been rising, the process of effectively closing coal assets is complex and requires significant additional effort from policy makers, utilities and investors. This includes widespread adoption of emerging approaches to managed phase-out as a net-zero-aligned transition finance strategy. Around 190GW of CFPPs will need to be retired in EMDEs to reach net-zero emissions by 2030. This will also require a transformation of the corporations, utilities, and communities that have historically relied on the operation of these assets, and bold policy support to ensure a just transition.

- Voluntary carbon markets can significantly aid the decarbonization of EMDEs if scaled effectively. They offer financial incentives for reducing emissions across various sectors, including coal phase-out. While current global volumes are modest, EMDEs are the primary source of carbon offset issuance and accounted for around 68% of the total in 2022. Market uptake of voluntary standards to ensure credit quality and integrity on both the demand and supply sides are likely to support further scaling.

[1] Throughout the report, emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) refers to EMDEs excluding China.

[2] Fossil fuel energy supply capital investment includes the upstream, midstream and downstream value chains of oil, natural gas and coal production and processing, as well as unabated fossil-based electricity supply.

The full report is publicly available here.