This article first appeared on Bloomberg View and the Bloomberg Terminal.

The Bank of England’s Prudential Regulation Authority has begun its latest stress test for general and life insurers. This biennial exercise tests the insurance industry’s market resilience to physical events of the sort that have garnered a lot of media coverage in recent years: hurricanes, earthquakes, tsunamis, windstorms, floods. It also includes two new risks: climate change and cybersecurity.

The Bank of England requires companies to consider how certain climate-related scenarios would affect their business, each with transition risks as economies decarbonize and meet the climate targets of the Paris Agreement and physical risks.

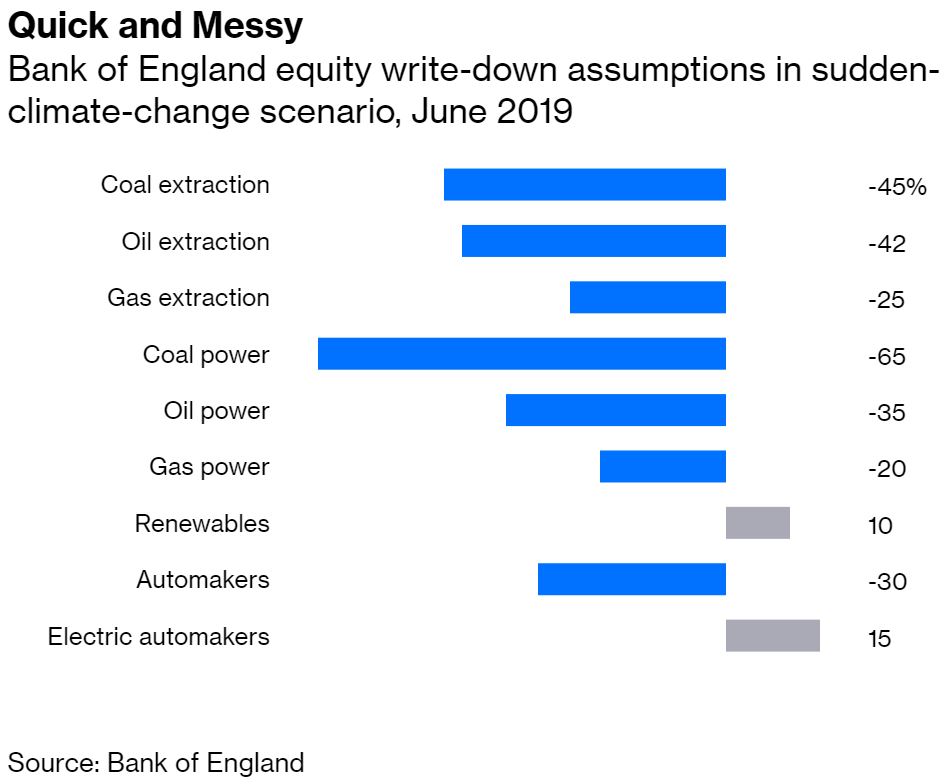

The first scenario is one of quick change and “disorderly transition” in order to meet the targets:

A sudden transition (a Minsky moment), ensuing from rapid global action and policies, and materialising over the medium-term business planning horizon that results in achieving a temperature increase being kept below 2°C (relative to pre-industrial levels) but only following a disorderly transition. In this scenario, transition risk is maximised.

This scenario involves some significant write-downs in specific asset classes. The Bank of England asks general insurers to make changes to the equity value of “sections of the portfolio comprising material exposure” to energy and transport sectors:

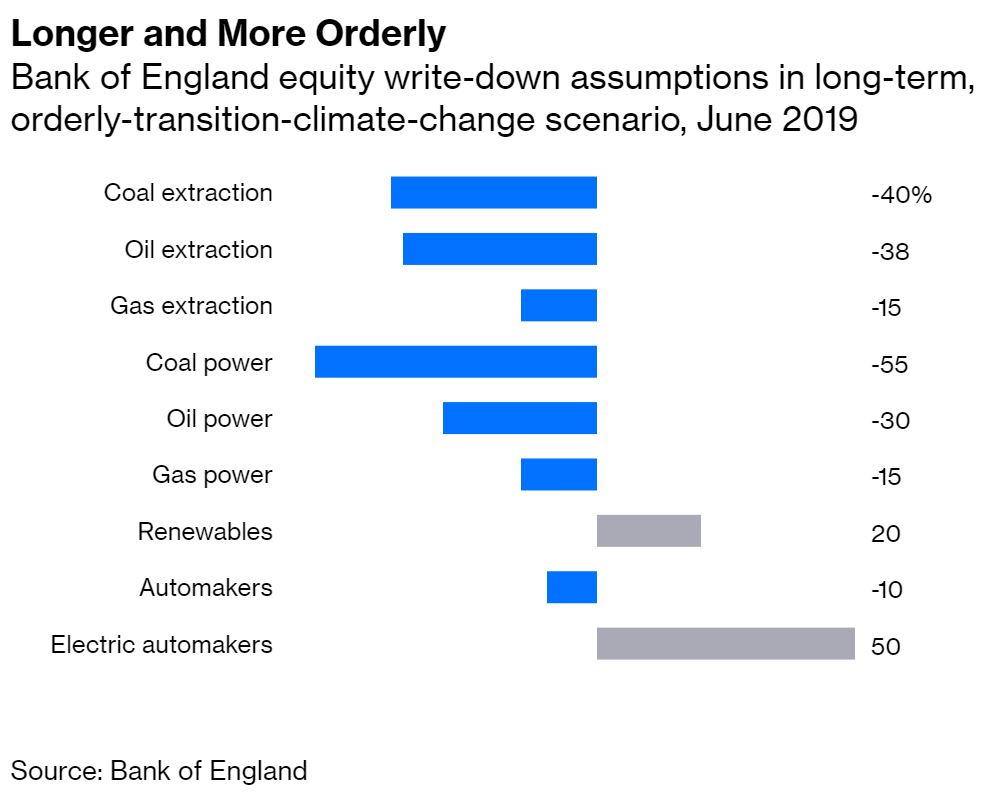

The second scenario is one of “a long-term orderly transition” to carbon neutrality by 2050:

A long-term orderly transition scenario that is broadly in line with the Paris Agreement. This involves a maximum temperature increase being kept well below 2°C (relative to pre-industrial levels) with the economy transitioning in the next three decades to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 and greenhouse-gas neutrality in the decades thereafter.

The write-downs in this scenario are not as significant. At the same time, the increase in equity values for renewable power generation and electric automobile manufacturers is greater:

I was struck by the logic of grouping climate change and cybersecurity as new risks to test. Both are global; both are pervasive; both have a very broad range of vulnerabilities that will impact business.

Climate change affects companies that contribute to atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, as well as those that will feel the impacts of rising sea levels, floods or fires, changes in where people choose to live, or changes in consumption patterns. But it’s probably easier to count the few areas of modern life not subject to cybersecurity risk than to outline the countless areas that are. When hackers can use internet-connected fish tanks or the remote controls on motorized hotel curtains to breach network security, it’s hard to think of where one is safe from cyberthreats.

But I also reflected on a paradox in the bank’s stress-test scenarios. Cybersecurity is a readily apparent threat in the near-term, but the bank’s risk scenario is so broad that “firms should consider claims arising from all lines of business in addition to stand-alone cyber products.” Meanwhile, climate change is not currently as apparent a threat in many places, and while its implications will play out in decades or centuries, the bank’s risk scenario is specific to asset classes and business lines.

Exercises such as this one, however, should serve to pull both of these pervasive risks and broad attack surfaces into the same frame of thinking about risk. Cybersecurity also becomes a matter of the long term; climate change becomes something increasingly present today, too.