This article first appeared on Bloomberg View and the Bloomberg Terminal.

In a prescient 2011 essay, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen declared that “software is eating the world.” Six years on, software is eating more of the world than ever — and it is also creating. One of those creations is digital twins, virtual models of industrial equipment, built up with gigabytes and terabytes of sensor data, that allow companies to remotely monitor the performance of power plants, jet engines and … well, anything worth monitoring, really. These digital twins will create numerous opportunities for companies and their clients, as well as raise challenging questions.

Digital twins aren’t unique to a particular kind of company, though industrial conglomerates General Electric Co. and Siemens AG are their most visible proponents. The technology represents an evolution within industrial firms and the logical outgrowth of a number of factors that my Bloomberg New Energy Finance colleagues have identified: cheaper and better sensing, processing and data transmission.

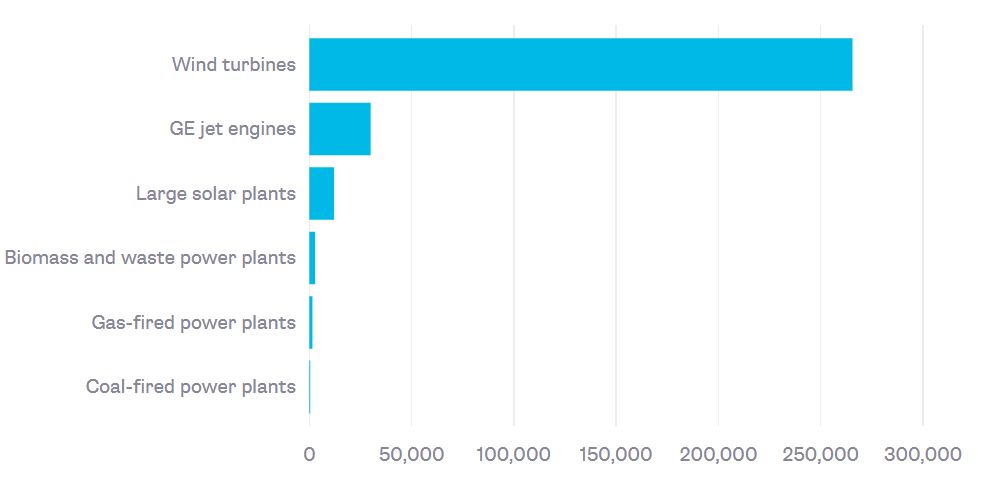

It’s also early days for the technology. Research firm Gartner puts digital twins in the “innovation trigger” phase of its Internet of Things hype cycle. Still, the potential market for digital twins is already large, even within a select group of energy and transport assets. Consider wind turbines, which have seen 265,000 installed since 2000. Wind turbines alone are a far larger market for digital twinning than the 30,000 jet engines in GE’s digitized fleet.

Many Potential Twins

Selected energy* and transportation assets

Sources: Bloomberg New Energy Finance, GE

*Energy assets commissioned since 2000

The market for digital twins in fossil fuel power plants may seem smaller (BNEF tracks only 477 new coal plants commissioned since 2000), but each one contains dozens, perhaps hundreds, of pieces of equipment that could be digitized. That market will only grow, as the number of devices that can be digitized grows and the cost of digitizing them drops.

So which industries are best situated to own and operate digital twins? Ed Crooks of the Financial Times explored the industrials-versus-software question in an article this week: In Crooks’ words, “what is it exactly that they do?” Is a turbine manufacturer a maker of dumb metal for a software company to optimize? Is software a service and support for industrial operations, or are industrial operations the input to a software-determined set of processes or even businesses?

Another question: How many digital twins is too many? Take those 265,000 wind turbines and GE’s 30,000 jet engines; both have spinning rotors and can and would need to capture much of the same types of data. Then there are the 15,000 solar projects — but those projects are each made up of tens of thousands (even millions) of individual solar panels as well as other pieces of equipment. What is the twin of a solar project? Is it the entire plant? The inverter “string” of hundreds of solar panels? Or will a solar project’s digital twin be a family of twins, so to speak, each a single solar panel? As processing becomes cheaper, as sensors become better, as data transmission becomes both, is there a logical upper limit to how many digital twins the world can have?

A final question: What is the liability paradigm in a world of digital twins? A digital twin could assess an impending failure in a piece of industrial equipment, and a company could fail to act on it. Or a digital twin could fail to predict a failure, and industrial equipment could suffer. Where is the liability in such scenarios?

To put it another way: Are digital twins the black boxes of the world? And if so, how long before a digital twin is called to testify against its physical counterpart and its corporate operators?