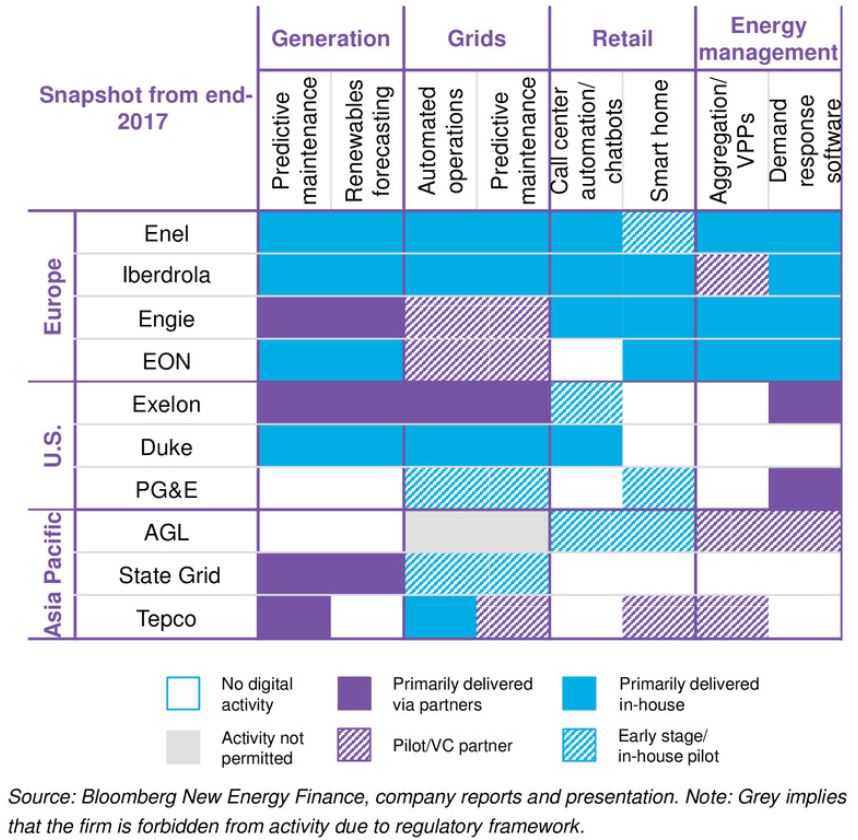

As the potential savings from digital technologies in the energy sector become clearer, more utilities are looking to take control. A recent BNEF study found that utilities are often bringing digital platforms in-house, and not just relying on third-parties for new techniques and services.

It is fair to ask why utilities would do this: developing digital platforms requires a significant amount of programming experience and an entrepreneurial attitude, both of which traditional utilities often lack. The new technologies are far from mature, which means there is a risk of in-house systems becoming obsolete as further innovations emerge. Indeed, an alternative such as partnerships would allow utilities to spread the risks — after all, startups and tech firms can be better placed to adapt to this rapidly changing environment.

So why take that risk? Utilities are building services in-house because it makes the integration of third-party supplier hardware easier, and because it allows for a level of customization and ownership that cannot be achieved otherwise. Many electric utilities want to own the IP and create a name for themselves as a progressive business. Some utilities, in addition, have a ‘build it yourself’ attitude or are encouraged to take activities in-house by their rate-basing structure.

There are short-term benefits, too. As most digital systems are still in their early stages, any partners brought in may be no better at delivering results than the utilities are themselves. Starting in-house now will help utilities gain the experience needed to identify good service providers. That said, it is a gamble: in the long run utilities may struggle to keep up with specialized providers as the specialists will probably be more dynamic, reach scale in data more easily through access to multiple firms’ sites, and yes, they will be better equipped to adapt to the changing technology environment.

Scope of digital activity for selected companies

In the meantime, one good reason for building digital platforms in-house is the need to bridge multiple technologies. One company’s wind portfolio – or even a particular site – may have turbines from multiple suppliers, for instance. The same is true for grids, where the platform may need to connect wires, circuits and meters from different sources. Utilities need to develop platforms that can integrate these different systems.

Power plant customization is another challenge. Every plant is different, and this is especially true for older hydro and thermal assets. The results of data feeds, and even the placement of sensors, can vary significantly from site-to-site. Given all these complexities, an in-house platform can be easier to troubleshoot and adapt.

A third motivation to bring digitalization in-house is the freedom to alter and adjust applications according to the utility’s own schedule and needs. A company’s understanding of its digital requirements evolves with more and more use. This means that the applications it runs must be fluid, and can be replaced or updated alongside the utilities’ own workflow. That can be easier to execute in-house rather than relying on a partner.

Beyond these practicalities, many firms see a proprietary digital platform as a competitive advantage. Enel and Iberdrola SA both believe their digital platforms will give them a cost advantage over peers. Enel sees developing digital platforms as a way to set industry standards and develop additive partnerships.

Finally, a subset of firms are looking at digitalization as a way to bolster their reputation in third-party service. EON SE is looking to license its predictive maintenance platform for wind farms to third-party projects that sign an operation-and-maintenance contract. Japan’s Tokyo Electric Power Co. and China’s State Grid Corp. are also considering digital platforms as a third-party service, while U.S.-based Exelon Corp. may seek to sell its drones to other utilities.

BNEF clients can see the full report on the Terminal or on web.