By Itamar Orlandi

Head of Frontier Power Research

Bloomberg NEF

UN delegates are meeting this week in New York to take stock of progress towards the sustainable development goals. This year’s focus is on ensuring access to affordable and reliable energy, safe and resilient cities and water. Our recent report titled ‘Powering the Last Billion’ highlights that these topics might be a little less intractable and rather more interrelated than they first appear.

Since Thomas Edison launched the world’s first utility in 1882, the dominant framework to provide electricity has been a large power plant and a network of ‘poles and wires’ for distribution. Electricity has since become one of the most basic components of modern life, often taken for granted. Yet, 136 years on, the industry is still not in a position to serve some 14% of the globe’s population. At this pace, some 700 million people will still not have power by 2030.

Our analysis, launched in conjunction with Bloomberg NEF’s New Energy Outlook, looked at whether off-grid solar and microgrids can ‘leapfrog’ the grid. What did we find?

1. The high costs of grid connections often favor decentralized renewables.

Energy generated from a solar home system can cost more than $1.5 per kWh and a community-level microgrid anywhere between $0.29-0.77/kWh – both multiples of the retail power price. However, extending the grid to a household that is not currently connected can cost anywhere between $266-2,100. In richer regions with a lot of economic activity, this fixed cost of connection can be amortized over relatively high rates of electricity consumption. But some 892 million of those without power live on less than $5.5 per day, with very modest power demands. To serve them, the costs of connection can more than double the retail cost of electricity, bringing it up to $1/kWh. That is more than the cost of power from microgrids, or of effective power from solar home systems when bundled with energy-efficient appliances.

2. Solar home systems and microgrids can become a $64 billion market by 2030.

There are still plenty of areas near population centers that lack electricity, where it makes sense to extend the grid. For example, some 15% of people without connections live in cities and that proportion is rising. Utilities and regulators are likely to focus on these sectors in the coming years, given that the grid is a trusted technology. But from the mid-2020s onwards, decentralized technologies will be able to bring electricity for the first time to more people than the grid, through a combination of cheaper components, established supply chains, consumer uptake of solar home systems, and fewer remaining locations where competing grid extensions remain economic. Of the 238 million new households to get electricity between now and 2030, 72 million will use solar home systems and 34 million will benefit from microgrids.

3. Reaching universal access to electricity could be significantly cheaper than most current expectations.

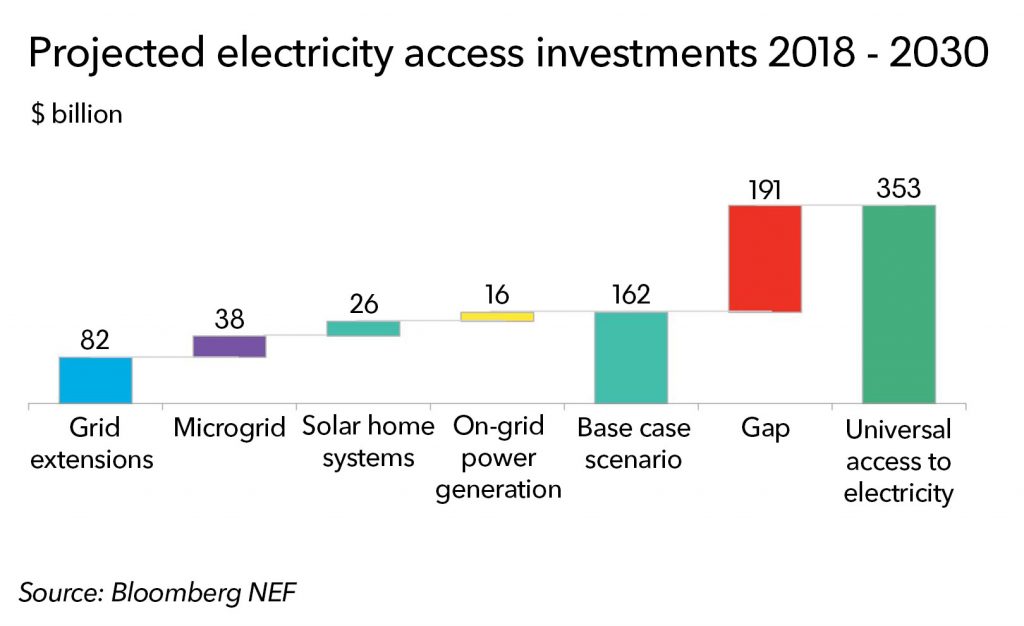

In our base case scenario, some 365 million people would remain unserved by 2030 despite a dramatic increase of microgrids and solar home systems. Reaching universal access and serving everyone with slightly more than just lighting would require spending an additional $191 billion on top of our current base case. The total, some $353 billion, is less than half than of the estimate by the International Energy Agency, which pegged the figure at some $725 billion. The IEA broadly agrees with our view on the crucial role of microgrids and solar home systems, but appears to assume costs well above those we already see in the market.

4. Energy giants are starting to develop energy access businesses.

Companies such as Shell (through its New Ventures arm), Engie or Enel all have in-house teams or partners building microgrids, selling solar home systems or developing supporting technology. Six of the 20 largest utilities and oil companies have committed to provide energy access to at least 52 million people by 2020. Corporate philanthropy is nothing new, but these initiatives are now being driven directly as part of their emerging markets or technology businesses.

5. The private sector is needed to fully unlock this potential.

The switch from large coal and hydro plants to solar-based microgrids and off-grid systems also decentralizes the manner in which these systems are deployed, improved and maintained. The entrepreneurs in the field use data and connectivity to manage assets and customer relationships, focus on retail distribution, and reinvent the way in which power is sold. There are endless possibilities for new combinations of technologies, process innovation and joint offerings with other services or sectors. For instance, we calculate that adding day-time load from agricultural equipment such as water irrigation or cold storage could reduce the cost of microgrid energy by some 18%, while allowing local communities to raise revenue from their crops.

These findings demonstrate that whilst ‘solving’ energy access by 2030 is certainly not easy, it is now more feasible than ever. The delegates in New York should focus on building the regulatory and financial frameworks and support from businesses needed to accelerate and sustain these powerful trends.

BNEF clients can see both the full Powering the Last Billion report on the Terminal or web and the New Energy Outlook 2018 on the Terminal or web. If you would like to learn more about becoming a client, please contact us.