By Vandana Gombar

Policy Editor

Bloomberg NEF

There is an ancient Indian fable about a bird with two distinct heads that do not always agree with each other. One head ends up plotting against the other after a dispute.

Now imagine that two headed bird to be multi-headed, like a hydra: India’s energy policy sometimes seems to be framed by just such a multi-headed being looking in different directions, with the heads often contradicting each other. For instance, government talks loudly in favor of new renewables, and on other occasions in favor of new coal power.

However, if you can drown out the day-to-day noise and bustle – as far as India is concerned, that is not easy to do – you might start to discern something surprising. The country that once argued vehemently that it needed, and deserved, “carbon space for development”, is now leaning more and more sharply towards cleaner options.

The stakes could hardly be higher. On the one hand, there is the health and comfort of the world’s second largest population, at 1.3 billion. On the other, there is the world trajectory for carbon emissions and climate change, and India’s pivotal role in those projections. To adjust an old saying about Paris sneezing and France catching a cold, if India chokes, the world will overheat.

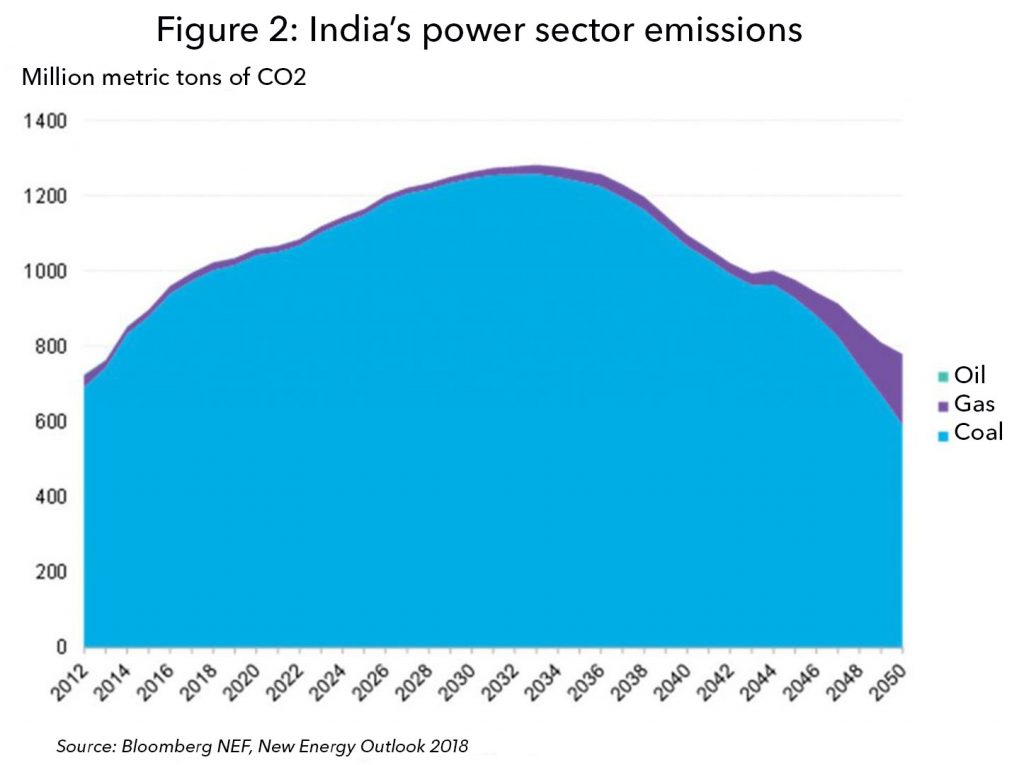

In its 2018 New Energy Outlook, BNEF projected that India’s power sector emissions would peak in 2033, some 29 percent above current levels, and then fall so that by 2050 they are 22 percent below 2017 levels. (The New Energy Outlook, or NEO for short, is based on the evolving economics of different generation options, and assumes no new policy measures. See chart at end of this article.) Only two years ago, NEO was projecting a trebling of India’s emissions from electricity generation between 2016 and 2040, by far the biggest upward influence on global power sector CO2 in that period.

Let’s see what we can glean from the momentum of policy on pollution and clean energy.

Local pressure

There is a significant and growing constituency in India that is vocal about emissions close to populated areas – including from thermal power plants – and their health impact. Policy-makers first responded in 2015 by framing stringent rules for emissions from power plants with a compliance deadline of December 2017, and then (back to the hydra perhaps) pushed the deadline for controlling emissions out by five whole years to 2022.

That delay could be interpreted to mean there was no seriousness about tackling emissions from power plants. There was speculation that when the year 2022 arrives, India may push the deadline further. But will India really choose to do that?

“What about the health of the people? Is it irrelevant?” the highest court in the country last month asked the counsel appearing for the Ministry of Power on a matter related to the severe air pollution in Delhi, according to New Indian Express.

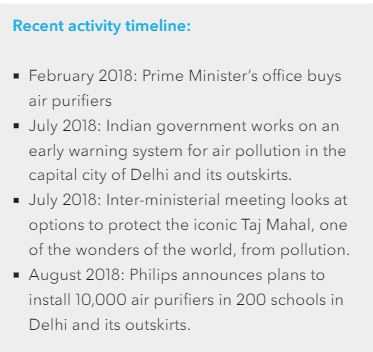

Sales of emission control equipment for power plants are picking up, and individual households and offices are also trying to clean their own air by installing purifiers. There was quite a buzz earlier this year when the Prime Minister’s offices were kitted with air purifiers. It was an acknowledgement at the highest levels of the problem of dirty air.

And then there has been the example of a very old coal-fired power plant being ordered to shut down, albeit temporarily, in the capital city of Delhi – due to deteriorating air quality.

That move might not sound like too much to foreign ears, but it was a stunning event in India. A coal-burning plant in India – a country that gets over 70 percent of its power from burning the black stuff – gets shut down due to pollution. The episode suggests there is a threat to every other coal plant that is operating or under-construction near population centers in the country, especially when alternative sources of energy are being aggressively set up. Incidentally, the load factor of coal and lignite based plants in India’s 344-gigawatt grid – the world’s third largest – fell to 61 percent last year, from 78 percent a decade ago, according to power ministry data.

In another part of the country, the local pollution control board ordered the closure of a copper smelter owned by Vedanta Resources after as many as 13 deaths due to police firing on people protesting against alleged pollution from the plant, and plans to expand it. Some saw it as the mainstreaming of pollution concerns while others continued to brand it as a conspiracy hatched outside India to maintain the country’s dependence on copper imports.

Aiming high

A National Clean Air Program is in the making to monitor and manage air pollution. The 6.4 billion-rupee ($90 million) proposal includes a significant outlay for “manpower and infrastructure augmentation” of the federal and state level pollution control boards.

The NCAP aims at taking the clean-air fight out of the federal center to the states and cities, where it is expected to make a significant impact. If the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi wanted to shy away from hard decisions or from a debate on air quality, it would not have launched the National Air Quality Index with much fanfare in 2015, according to one view. The real time monitoring of air quality, soon to be expanded to a wider sweep of cities and towns, has triggered serious debates and discussion on mitigation plans. That was the intention perhaps. It may have been a deliberate plan to nudge air quality on to the national stage to create the space for action. “We are measuring air quality across the country and publishing real-time data. There is an intention to solve the problem, instead of refusing to acknowledge it,” said Arun Kumar Mehta, the additional secretary at the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change.

A version of the graded response action plan (known as GRAP) is proposed for rollout across the country, laying out actions that need to be taken if the air quality deteriorates, especially in the 100-odd cities with the worst problems. These actions would include shutting down thermal power plants as well as diesel generator sets.

From cement plants to brick kilns – both figure in the 117 highly polluting industries identified by the government, as do thermal power plants – all units are being forced to monitor and control their emissions. There is room for mischief for sure in reporting them, and compliance checks are patchy, if they exist at all, but the direction of policy is clear.

On vehicular emissions, the government is proposing to jump straight to ‘Euro 6’ equivalent standards by 2020, from the Euro 4 standards currently in operation. It would not be easy to find another country that has made such a move. The capital city of Delhi has already moved to Euro 6.

Electric transport

India’s transport minister created quite a furor when he announced, in September 2017, that India would be an all-electric-car market by 2030. This idea has since encountered a dash of realism and has not translated into official policy. Nevertheless, various government-owned companies and departments are taking deliveries of electric vehicles secured via a 10,000-vehicle bulk procurement tender floated by an energy service company.

Meanwhile, there are a lot of electric three-wheelers visible on the roads of the country that are basically used for last-mile public transit. And orders are being placed for electric buses. BNEF expects buses worldwide to electrify before other types of vehicle since they offer quicker payback due to a higher number of miles travelled per period.

The Delhi government intends to buy 1,000 fully-electric buses and have them running on the roads by March 2019. China’s BYD, in a partnership with India’s Goldstone, won orders for 290 electric buses in the country earlier this year. Various state governments are opting for electric buses, attracted by incentives and savings on running costs.

Electric passenger cars are beginning to be seen, as are charging spots but, with the government deciding to channel subsidies for electric vehicles to public transport rather than private cars, their growth will be limited until they reach price parity with conventional internal combustion engine vehicles, which will be sometime in the 2020s.

Still in transport, Delhi metro is actually getting a good share of the electricity it uses from solar power that it has contracted from a plant in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. Interestingly, the metro company exposed itself to some project risk too, and signed on to a lock-in for power from the Rewa plant in exchange for savings of about $120 million over the term of the power purchase agreement.

Solar deployment

Coal-rich India is targeting solar build on a scale that is second only to China. It wants to bolster domestic manufacturing of solar panels as it moves toward its 100-gigawatt solar target, and it may be prone to a few errors on that path, having just imposed a safeguards duty on import of panels. But the pace is gathering. Solar capacity surpassed 23 gigawatts in July, and another 10 gigawatts are under implementation, while tenders for more than 24 gigawatts have been issued. “The nation is on track to comfortably achieve the target of 100 gigawatts of solar capacity by 2022,” Power Minister R.K. Singh told Parliament last week.

India will have the world’s largest installed base of solar by 2050 – almost 1,000 gigawatts, according to BNEF’s latest New Energy Outlook. Much of this expansion will be at the expense of the share of the country’s largest existing power source: “Coal’s role in the generation mix starts to diminish from the mid-2020s onwards,” according to NEO 2018. Coal power will be a mere 14 percent of India’s generation mix by 2050, and a mere 5 percent of capacity. The utilization of its plants will continue to be under pressure, given that more and more zero-marginal-cost solar and wind plants will be pumping power to the grid.

Green bodies show teeth

Earlier this month, the National Green Tribunal – a quasi-judicial body set up in 2010 to look into cases relating to environment and natural resources, and having the power to impose penalties – stood by its earlier order of not allowing 10-year old diesel vehicles on the streets of the capital city. In July, the green court had Volkswagen in the dock for not recalling all its polluting vehicles in the country.

Those aggrieved by the decisions of the NGT can approach the Supreme Court of India, which is itself been at the forefront of the attack on bad air. It has been asking the government to put a nationwide ban on the use of petcoke and furnace oil in industries, for instance. Such a ban is already in place in key states surrounding the capital, Delhi.

The Supreme Court is trying to rescue the iconic Taj Mahal, one of the wonders of the world, from the deleterious effects of pollution. It has been breathing down the neck of the federal government and the government of Uttar Pradesh state, where the monument is located, to ensure that pollutants from industries around the Taj are controlled.

The Central Pollution Control Board ordered the closure of Bilasraike Sponge Iron Industries on August 2 for violating emission norms, according to Times of India. As many as 366 polluting units in Uttarakhand were asked in May to wind up their operations. The CPCB, according to the same publication, knocked on the doors of the Tribunal last month when it found various government agencies flouting environmental rules on construction and demolition.

It was the state-level pollution control board that issued directions for the closure of Vedanta’s copper smelter at Tuticorin. The pollution control boards work under the direction of, and with, the government.

Power Minister Singh informed Parliament in December 2017 of a phased implementation plan for installation of equipment to control sulfur dioxide emissions (via flue gas desulphurization, or FGD) from 414 power generating units (161 gigawatts), and the upgrading of fine-dust-collecting electrostatic precipitators for plants totaling about 65 gigawatts. There are some plants that do not have the space for FGD systems, and their owners will need to explore alternative technologies in order to be compliant.

Pollution and GDP

India is no longer talking about being a developing country needing carbon space for development. It knows that the haze that envelopes the capital city especially in the winters is turning away labor and capital, besides playing havoc with the health of its residents.

The World Health Organization, in an update published in May 2018, said that nine out of 10 people in the world are breathing air containing high level of pollutants. Particulate matter in the air is a serious cause of concern: “Major sources of air pollution from particulate matter include the inefficient use of energy by households, industry, the agriculture and transport sectors, and coal-fired power plants.”

There are periods when the air quality in some Indian cities is worse than it is in Chinese ones, though China is far ahead of India in terms of economic output. Policy-makers understand the challenge for green growth that this represents. “The link between our air quality, our health and our GDP growth is well understood at the highest levels of government,” said Mehta of the Environment Ministry.

That is even without considering the possible backdraft that could hit India from climate change. A World Bank report published in June 2018 estimated that as much as $1.18 trillion of India’s GDP could be wiped out if global temperatures continue to rise.

Heads and body

I likened India’s policy-making to a bird with two heads, or more accurately a multi-headed hydra. Different heads continue to say different things. An example came last month when the country’s outgoing Chief Economic Advisor, Arvind Subramanian, spoke again about carbon imperialism of the Western nations. In the Economic Survey tabled in Parliament last year that he authored, he argued that taking “social costs” of renewables into account makes them multiple times more costly than coal.

However, if you are looking at a hydra, it makes sense to look just not at the heads, but also at the body. And, in India’s case, the body is heading in a clearer direction on emissions than ever before.