By Albert Cheung

Head of Analysis

BloombergNEF

In the early weeks of the year, as it became clear that the pandemic would be the story of 2020, we at BloombergNEF found ourselves fielding a continuous stream of questions about how energy transition and climate action would be affected. We re-worked our research agendas and started tracking every piece of data we could find, and we started to question our own forecasts. Could it be that the energy transition would take a step backward this year?

In April, in an effort to remain optimistic, I wrote that, despite the economic and health challenges unfolding before us, the 2020s could still be our greatest decade of climate progress, with massive acceleration across renewable power, electrified transport and other earlier-stage technologies.

As the curtain falls on a grim year, it seems that the mood of optimism is catching.

Four reasons for optimism on climate

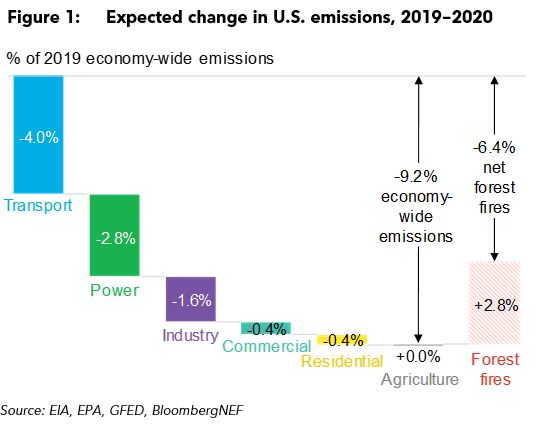

There are four positive signals from this uniquely challenging year. First, the direct impact of Covid-19 itself appears to have created a momentary opportunity. According to BNEF analysis, U.S. emissions are likely to be 9% down this year, which means that the only country to leave the Paris Agreement is suddenly (albeit temporarily) back on track to meet its original Paris targets. This effect is of course not limited to the U.S. – a similar number is likely to emerge globally – nor will it be limited to 2020. We now know that a V-shaped recovery is off the cards, and according to our New Energy Outlook 2020, published in November, the longer-term economic impacts of Covid-19 could mean the permanent avoidance of 2.5 years’ worth of global energy-related emissions. This effect could be greater if, for example, aviation recovers slowly.

It is important not to be triumphalist about this: these reductions have come at the expense of a great deal of human suffering. But we can welcome the result for emissions, even if we abhor the way in which it has been delivered.

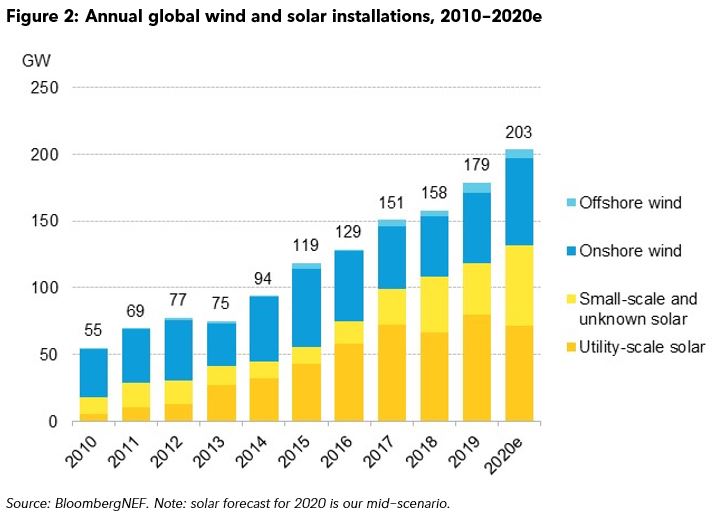

Second, the pandemic has not derailed progress on the energy transition. Even as power, gas, coal and oil have suffered, renewables and electric vehicles have continued their business as usual – or rather their growth as usual (GAU). It looks like our original, pre-Covid prediction that wind and solar installations could reach a record 200GW in 2020 may well be achieved. Even rooftop solar is doing well, against the apparent odds earlier in the year. Electric vehicle sales look set to grow by 28% this year – higher than our pre-Covid forecast – on the back of record European sales figures, despite the wider auto market being turned inside out. GAU is not nearly enough, a point to which I will return later, but at least low-carbon technologies have weathered the storm. This should not be taken for granted.

Other indicators show that climate and sustainability have taken steps forward this year, not back. European carbon prices are at all-time highs around 32 euros per metric ton. Corporate purchases of renewable power are tracking just ahead of 2019 levels, as of early December. ESG funds have seen record inflows throughout 2020, a direct response to the pandemic as investors seek resilient investments.

Corporate decarbonization goals have taken a step forward in both volume and ambition, with more Scope 3 targets and more net-zero pledges, from more different sectors, than ever. (BNEF clients can view these indicators on web or terminal).

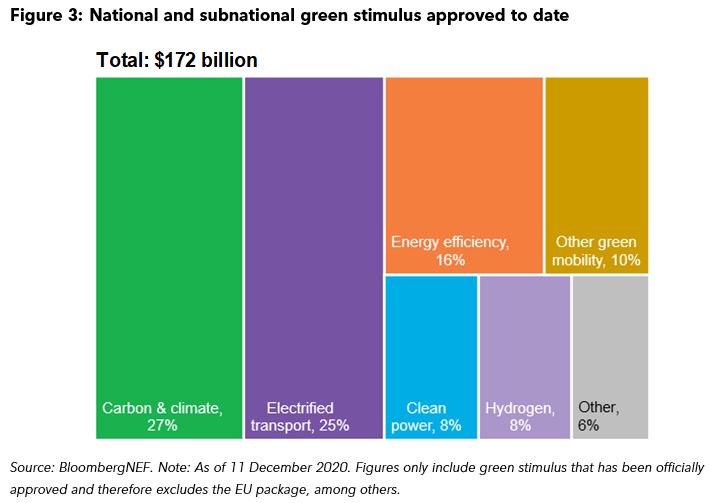

Third, early calls to ‘build back better’ are gradually being converted into real funding. Our latest Green Policy Tracker finds that national and sub-national governments have so far allocated $172 billion in ‘green’ stimulus funds, targeting areas such as electric and clean transport, energy efficiency, clean power and hydrogen. This sum is similar to the totality of green stimulus pledges made after the global financial crisis a decade ago, and as we know, those funds were instrumental in kick-starting clean industries and crowding in private investment. This time around, there are important countries still to announce green stimulus plans. The vast majority of approved funding so far comes from European countries and South Korea, with Japan now catching up. The U.S. and Australia are still notably absent. And of course, the EU’s stimulus plan, now all but approved, will put another $600 billion into green causes.

When all is said and done, post-Covid recovery funds might inject close to $1 trillion into the global low-carbon transition. It is impossible to know how much of this might have been forthcoming anyway, in a no-Covid parallel universe, but the answer is certainly not all of it.

Last but not least, 2020 has seen an unprecedented acceleration in national climate pledges – underlined by last weekend’s Climate Ambition Summit. China’s new commitment to bring its emissions to a peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, was reiterated on Saturday. It is perhaps the single most important development in climate policy since the Paris Agreement itself, five years ago. On that autumn day when President Xi Jinping first spoke those now-famous words, it became clear that this single statement would put pressure on every developed country to step up its ambition, and so it came as little surprise to see Japan and Korea make their own net-zero pledges a few weeks later.

The list goes on! At the Summit on Saturday, Argentina said that it will pursue carbon neutrality by 2050. In Pakistan, Prime Minister Imran Khan said that his country will build no more coal power, and achieve 60% renewable energy (he may have meant electricity) by 2030. The day before, the European Council endorsed the EU goal of reducing emissions by 55% by 2030. The week before that, the U.K. announced its new NDC[1] that pledges to reduce emissions by a massive 68% by the same year. (Both the EU and U.K. are already targeting net zero by 2050.) President-elect Joe Biden intends to set a U.S. net-zero target and, depending on the outstanding Senate race in Georgia, may push for much faster decarbonization across the U.S. economy. According to BNEF analysis, countries representing around 42% of global CO2 emissions now have ‘somewhat credible’ net-zero targets. (UNFCCC puts the number higher, but likely includes countries that have merely talked about such targets.)

In other words, this is the year when we began truly to appreciate the genius of the Paris Agreement. Built on common long-term ambition, rather than binding shared sacrifice, the deal was remarkably unaffected by the exit of the world’s largest economy. Rather than crumbling under the weight of rigid, inter-dependent obligations, it has instead created the conditions for countries to raise their ambition levels as circumstances have changed. With technology costs falling faster than expected, climate-related disasters mounting and citizens urgently demanding leadership, the Paris framework has created a race to the top.

The 2020s must be about focused execution and delivery

That race is only just beginning, but collectively, we are behind. The year of 2020 has given us the reset we needed – but it is only a window of opportunity – and one that won’t stay open for long. Indeed, this reset is probably the last chance the world has to get on track for ‘well below two degrees’. What policymakers do in the aftermath of Covid-19 will set the tone for this decade, and by 2030 we will know if we’ve blown the two-degree budget.

This window of opportunity comes with one major advantage: clarity. Developed-world economies now have 30 years to reduce their net emissions to zero. Work back from 2050, and what has to be achieved within this decade is not terribly hard to calculate.

The question is whether governments and the private sector can execute fast enough to achieve what is needed by 2030.

The U.K. example

The U.K., an early net-zero champion, has an independent body that advises government on climate-related issues. The latest advice of the Climate Change Committee, predicated on the legislated goal of net zero by 2050, calls for the U.K. to achieve 87% low-carbon power and 97% electric car sales by the end of this decade. (The latter is in line with government policy to phase out internal combustion vehicle sales by 2030.)

Comparing these figures with BNEF projections offers an indication of how difficult (or not) they will be to achieve. In our New Energy Outlook, under the Economic Transition Scenario, which assumes no further policy support for clean energy, the U.K. actually reaches 90% zero-carbon power by 2030, exceeding the CCC benchmark. However, passenger EVs only account for 42% of sales in that year in our base-case EV outlook,[2] if we don’t assume that government phase-out targets are hit. In other words, one of these goals looks a lot easier than the other.

Europe

Similarly, the European Commission’s impact assessment indicates that a 65% share of renewable electricity would be needed by 2030, to support its target of 55% emission reductions by then. Our NEO Economic Transition Scenario for Europe already gets to 63% renewable power by 2030 – within striking distance of 65%. On the other hand, BNEF analysis indicates that current fleet-wide CO2 standards in Europe only require EV adoption to get to a third or a half of passenger vehicle sales by 2030. These are set to be tightened further over the next year as the 55% target works its way down into automotive CO2 standards, and that could push the required EV share up to well over 60% of sales. But even this is unlikely to be compatible with getting to net zero by 2050, so there is clearly more work to be done on ICE (internal combustion engine) phase-out timetables in Europe. BNEF will be publishing a set of European policy scenarios in the near future.

The global picture

Our New Energy Outlook, or NEO for short, also offers a Paris-aligned pathway, on a global scale. The 2020 report includes a new Climate Scenario, in which global warming is held to about 1.75 degrees Celsius through rapid uptake of electrification, clean power and hydrogen. In this scenario, the world adds nearly 6,900GW of wind and solar between 2021 and 2030 – an average of 690GW per year. By 2030, 73 million metric tons of annual hydrogen production is in place, which would require nearly 900GW of electrolyzers if the hydrogen is produced solely using renewable power (as well as 1,300GW of additional wind and solar generating capacity).

How much faster is this, compared to a ‘GAU’ trajectory? As mentioned, global wind and solar deployments will land somewhere around 200GW this year – less than a third of the implied rate needed for the coming decade. If installations grow in line with our least-cost scenario to 2030, then the average rises to 270GW per year. Even that is far from what the doctor has ordered.

As for hydrogen, the EU’s plan to build 40GW of electrolysis capacity by 2030 is currently the world’s most substantial commitment. Globally, BNEF’s hydrogen database currently tracks just 17GW of forthcoming projects meeting our criteria for inclusion. Ambition: meet reality.

A moment of optimism and opportunity

In sum, this tumultuous year has given us several reasons to feel optimistic about the climate fight. We should take a moment to celebrate the progress made in 2020, and welcome the increased ambition from global leaders across both government and industry.

But that moment of celebration needs to be brief, because the window of opportunity is rapidly closing. If 2020 was the year of rising climate ambition, then 2021 needs to be the first of many years of focused delivery and execution.

The challenges, of course, are huge. Many of them have been discussed in other, recent BNEF comment articles: Don’t Get Euphoric – Risks Yet For World Energy Transition, and How Great Power Rivalry May Affect the Low-Carbon Revolution. Our first comment piece of 2021, next month, will make 10 bold predictions about how opportunities and challenges may play out in the year ahead.

In the meantime, the happiest holidays possible to all BNEF’s clients and friends!

[1] Nationally Determined Contribution

[2] Our forecasts are subject to revision and the next edition is likely to go higher.