By Vandana Gombar

Policy Editor

Bloomberg New Energy Finance

The Indian rope trick was a popular magical illusion of the 19th Century and beyond, involving a lot of smoke and other visual distractions, a coil of rope that uncurled and rose up improbably towards the sky and sometimes a small boy who climbed it.

With hindsight, perhaps it represented the towering ambition of its home country and the overcoming of obstacles. But the illusion cannot last forever: the rope would have to fall back down to Earth eventually.

Is something similar unfolding in India’s energy policy? When the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced two years ago the target of installing 100 gigawatts of solar capacity in India by 2022, it was seen as reaching into the sky by a country that had been, and still was, wedded to coal. Many commentators scoffed at the number, though their voices have been hushed to some extent since — by the capacity that has actually been built.

Solar will certainly be huge in India, but will it be huge enough, combined with other low-carbon technologies, to deflect the country from a coal-intensive development path? It is a vital question not just for India itself, but for the world also. Bloomberg New Energy Finance’s latest long-term forecast for world power generation — the New Energy Outlook, or NEO — published in June, showed that the current course could mean Indian emissions trebling between now and 2040, and being the biggest single challenge in the way of global attempts to keep CO2 below the 450-parts-per-million mark.

Solar awakening

The 100-gigawatts solar target was set in 2014 by the government of Prime Minister Modi. Was this a serious target? Was India trying to be a China? India is the only country, other than China, with a population of over 1 billion, but the two neighbors are very different.

Whereas China is a centrally planned economy, with a track record of hitting the targets it sets itself (in multiples sometimes), India has a federal structure where both the central government and the states are responsible for energy policy and often work at cross-purposes. It is messy and littered with bankrupt buyers of power owned by often profligate state governments. This makes investment difficult and change slow to happen. If we had said in 2008 or 2009 that India would have 7,500 megawatts of solar installed by early 2016, we would have been told that it was technically feasible, but impossible. India is often depicted as an elephant. Elephants move with slow, sure steps. They are not exactly agile.

Who could have foreseen that international project developers and some of the world’s largest power utility companies would soon be lining up to invest in India’s renewable energy sector? India had very limited success in attracting foreign investment in its conventional power sector, despite repeated attempts. What is more, solar projects have been awarded largely through capacity auctions — procedures that can give rise to concerns about “spiking of specs [specifications]”. In other words, a government designs processes that are meant to be competitive but actually favor a select few.

In fact, in India, the process has been relatively smooth so far. No one could have predicted that the record for the lowest solar bid in India would be held by a subsidiary of the Fortum OYJ Finnish utility (Fortum Finnsurya), and that the bid would be not far off 4 rupees (6 U.S. cents) per kilowatt-hour.

The record for the second-lowest solar bid in the country is held by SunEdison Inc, the bankrupt PV giant that is now in the process of trying to sell its 1-gigawatt pipeline of projects in India, and there seems to be no lack of interest from international buyers. For instance, Singapore’s Sembcorp Industries Ltd. recently increased its stake in Green Infra; while earlier this year, Malaysian utility Tenaga Nasional Berhad announced the purchase of a 30 percent stake in a “select portfolio” belonging to GMR Energy Ltd. Italian utility Enel SpA owns a majority stake in wind power producer BLP Energy Pvt Ltd. Norway’s Statkraft AS formed a joint venture with Bharat Light & Power Pvt Ltd late last year to provide distributed solar energy systems. And Engie SA, through its subsidiary Solairedirect SA, is also a familiar name in the country, bagging solar projects at low tariffs. There are domestic groups looking at growth by acquisition too. For instance, Tata Power Co Ltd agreed to buy Welspun Renewables Energy Pvt Ltd’s total portfolio of 1.1 gigawatts last month.

Enel has so far stayed on the sidelines in the Indian solar market. Last month, Antonio Cammisecra, head of business development for Enel Green Power, told Bloomberg New Energy Finance: “In India, we require a certain rate of return. This reflects the fact that there is no inflation-proofing in the PPAs [power purchase agreements], and there is rupee exposure. Some other companies are OK with a 12 percent return in India, but not Enel.” However, when asked what would be the next big market for Enel, after Latin America and South Africa, he voiced optimism: “Well, we hope it will be India. I still think Enel can play a big role there.”

The no-regret path

How cheap is India’s solar? Well, the lowest bids are about a third the price of power from diesel. But why compare with diesel? The latest official figures from India show 300 gigawatts of power generating capacity, 60 percent of which is coal, followed by gas at 8 percent, and less than 1 gigawatt of diesel power. However, the country has a dirty secret in the form of almost 100 gigawatts of diesel generator sets, that kick-in to supply power when the grid fails to deliver. And this happens regularly. It is estimated that as much as 25 percent of the country’s total capacity is therefore accounted for by diesel, which is one of the most expensive and polluting ways to produce electricity. At 6 U.S. cents per kilowatt hour, solar makes a lot of sense — a “no-regret measure” to borrow a phrase from former Indian climate negotiators.

However, since the solar panels being deployed are mostly imported from China, questions have started to be asked about who is really benefitting economically from India’s solar drive. There is increasing noise about domestic manufacturing. However, a move in this direction coupled with local content requirements to support production will inevitably result in higher costs.

Despite solar’s apparent success in India, there are those who question whether a PV plant can actually deliver power at 6 U.S. cents. They might have a point — or not. It was only 12 months ago that Saudi developer ACWA Power won a 200-megawatt solar tender in Dubai at a record 5.8 U.S. cents. Since then we have seen successful solar bids in Mexico at 3.5 U.S. cents and Dubai again at just under 3 U.S. cents. In Zambia last month, under a World Bank-backed program titled Scaling Solar, there was a winning solar bid at 6.02 U.S. cents. All these prices hide small print about inflation, timing and financing terms that make them hard to compare directly, but solar at 6 cents and lower seems to be increasingly normal.

Solar developers are also starting to look downstream towards the rooftops of commercial and industrial consumers. The basic regulations to kick-start this market have just about been sorted out, and most of India’s states now have net-metering rules allowing solar power to be sold back to the grid.

Wind farms are pretty

The wind sector has had a longer, though mixed, history in the country. Aishwarya Rai, who was Miss World in 1994 and later a Bollywood actress, and Indian cricket legend Sachin Tendulkar were among those who owned turbines because there was tax to be saved. The model of development in India was also distinctive: it was the turbine manufacturers that developed projects and offered turnkey projects to investors. And there was a generous feed-in tariff to make all this possible. In contrast, the solar sector was really born in auctions. Now the price of solar is lower than the feed-in tariffs for wind.

The wind industry resisted auctions, and it is now seeing the fall-out. New projects that are ready to commission are sitting idle because their developers cannot finalize PPAs at the generous feed-in tariffs of yore, and some that have secured those deals are not getting paid. The buyers of power — mainly the state distribution companies — are simply preferring cheaper solar power.

As a result, India is now due to start auctioning wind projects, despite the long and strenuous lobbying against that.

Wind farms have another thing going for them in India, and in many countries in Asia. No one thinks they are ugly. They are rather a sign of development, progress and power. Not only is there scope to add farms on the land, and offshore, there is a neat repowering market gradually opening up. A plan to allow solar panels to be installed on a wind farm, or vice-versa, could bear fruit soon, with the government close to finalizing a wind-solar hybrid policy.

Brimming

Meanwhile, everyone is brimming with ideas. I recently met the president of the Wind Independent Power Producers Association and also the chief of Hero Future Energies Ltd, Sunil Jain, who is not alone in lamenting the slow progress of the Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO) and the Renewable Generation Obligation (RGO). He argued for a more direct Renewable Consumption Obligation, or RCO, on commercial and industrial users —starting at 10 percent.

Renewables and coal minister Piyush Goyal has toyed with the idea of dollar-denominated tariffs — to take away the sting of currency volatility on returns — a move that could swing many fence-sitters towards making actual investments. A draft national policy on renewable energy based microgrids was released last month. Something is also cooking in the bio-energy space. Training courses for technicians are being offered at over 100 locations across the country with the cost underwritten by the government, and, the world’s largest efficient-lighting program is currently underway in India.

One can also see the first stirrings of renewables demand from corporate India, driven by a desire to be responsible corporate citizens, and to attract and retain what may be called “ethical” capital. Two companies, Tata Motors Ltd. and Infosys Ltd, have committed to 100 percent renewables, the latter by 2018.

Demand is also expected from international groups with operations in India that have made the same commitment, such as Google Inc. and Unilever PLC. The Tata conglomerate decided last month to adopt an internal carbon price.

Surplus coal & power

At the same time, coal production is rapidly picking up pace in India. The new government has set a target to produce 1 billion metric tons annually by 2020 — up from 536 million metric tons in 2015.

India’s dominant source of electricity is coal and, in theory, the country has a pipeline of as much as 80 gigawatts of coal plants — the largest in the world. Our New Energy Outlook 2016 forecast puts the likely gross addition at 258 gigawatts by 2040, offset to a small extent by 49 gigawatts of decommissioning.

How likely is it that India will veer off this coal-intensive trajectory? One straw in the wind came in May, when Anil Swarup, the coal ministry’s top bureaucrat, hinted that the actual capacity built could be significantly lower than the official pipeline.

From a climate perspective, an optimistic view might be that perhaps India will not need so much power generation, thanks to efficiency initiatives and the realities of poverty.

There are certainly many people willing to consume more power as they get grid connections as part of India’s Power-For-All program, but the number of them actually able to do so may be limited. This is because India still has millions of poor people who require subsidies to afford even basic lighting. That would partly explain why India is set to show a power surplus for the fiscal year ending March 2017, despite there being ongoing shortages in some regions, and almost 240 million people without any access to electricity. Interestingly, India, a coal importer, is now also contemplating exports of coal.

Public opinion matters too. It is not uncommon to see the choice of the power source being debated at neighborhood cafes, as pollution masks and traffic restrictions kick in, especially during the winter months. This was not the case a few years ago, when the focus was solely on getting electricity. The idea that a starving man just wants food, not necessarily healthy food, does not seem to be the view of an increasing number of Indian civilians. We have now seen protests against coal-fired plants in India and other parts of the region, and at least one attempt to shut down a running plant in the capital city to control pollution.

The swing emitter

One of the major conclusions of our NEO 2016 forecast is that India is one of the keys to the level of global emissions in the future. Our modelling suggests that by 2040 India will account for 23 percent of world power sector emissions, or 3.1 gigatonnes out of the world’s total of 13.6 gigatonnes. But that outcome is far from inevitable. Our NEO forecast is not a prediction, it is a scenario that describes the long-term economics of supply and demand in the power sector. Those economics are ultimately influenced by policy decisions.

India is taking steps to try to bend its future in a less carbon-intensive direction. It has a modest but rapidly increasing tax on coal, known as the coal cess — collections are estimated at about $4 billion for the year ending March 2017 — and there is talk of making the washing of coal mandatory before use in power stations. Last year, India submitted its emissions target, or INDC (Intended Nationally Determined Contribution) ahead of the UN climate change conference in Paris, committing the country to reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 30-35 percent by 2030, relative to 2005 levels, and to increasing the share of non-fossil-fuel based energy resources to 40 percent of installed capacity by the same year. This would mean stretching its renewable energy target of 175 gigawatts by 2022, to 300-350 gigawatts.

The headline on this article asks, cynically, if the country’s targets could be an Indian rope trick, in other words a distraction behind which it will go on building more and more coal-fired power stations. Fittingly, one of the explanations for that famous old magic trick is that the rope tended to be thrown upwards in front of the sun, to prevent the audience getting a clear view of what was going on.

However, the evidence is building up that India’s renewables policy is no optical illusion. I might add that the Indian rope trick eventually declined in popularity, as audiences became harder to convince — and more familiar with the amazing things that could be achieved with real-world technology. And today, real-world technology, to a large extent, means solar.

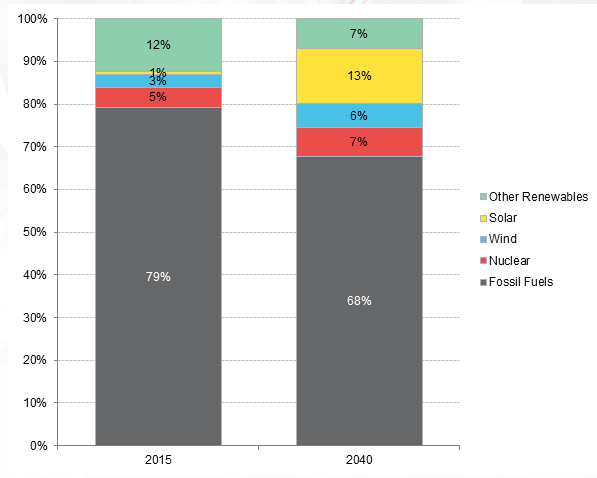

Generation mix, 2015 and 2040 (%)