ARTICLE

The Food and Agriculture System Will Change. The Question Is Not If, But When and How

By Hugh Bromley, Head of Food, Agriculture and Nature at BloombergNEF

The farming and food system has an enormous impact on the planet, responsible for over a third of global greenhouse gas emissions and the leading driver of deforestation, water stress and branded plastic pollution. It is also unmatched in its co-dependency with the natural world and vulnerability to the impacts of climate change.

Change is therefore inevitable, but its path is undefined and the scale of disruption is uncertain. Under one transition scenario, the environmental impacts of the farming and food system are redressed through emergent technology, sustainable land practices, policy and targeted investment. In another scenario, failure to act leads to a food system transformed by its vulnerabilities to changing weather and rainfall patterns.

BloombergNEF’s recently released 2025 Food and Agriculture Transition Indicators report highlights the connection between agricultural markets and the climate transition. It contains 47 indicators of change already underway across the food and agricultural system, encompassing: sustainable proteins, regenerative practices, green agrochemicals, advanced machinery and agtech, crop science, and climate risk. BNEF clients can access the full report here.

The 2025 edition highlights a bifurcated transition. On the farm, agricultural productivity and production value are rising to meet the needs of a growing global population with increasing appetites. Farm practices are also becoming inherently more efficient and sustainable: nitrogen-use efficiency is rising, farmers are using fewer pesticides, and no-till farming and cover crops are becoming more commonplace. Beyond the farm gate, the agriculture transition is showing signs of stalling: early-stage investment in the sector is plummeting, agtech firms are going bankrupt, and some large companies are backtracking from targets.

Action on the farm

Food and agriculture companies are working with farmers to support sustainable land management. They have already established around 7.5 million hectares of regenerative agriculture projects globally, an area almost twice the size of Switzerland. In the US, no-till or low-till farming practices that limit soil disturbance are deployed across almost three-quarters of planted acres. The area under regenerative management is set to double by the end of the decade, to a combined 15.8 million hectares, providing the pipeline of projects already announced by a cohort of 155 agri-food firms is delivered on schedule.

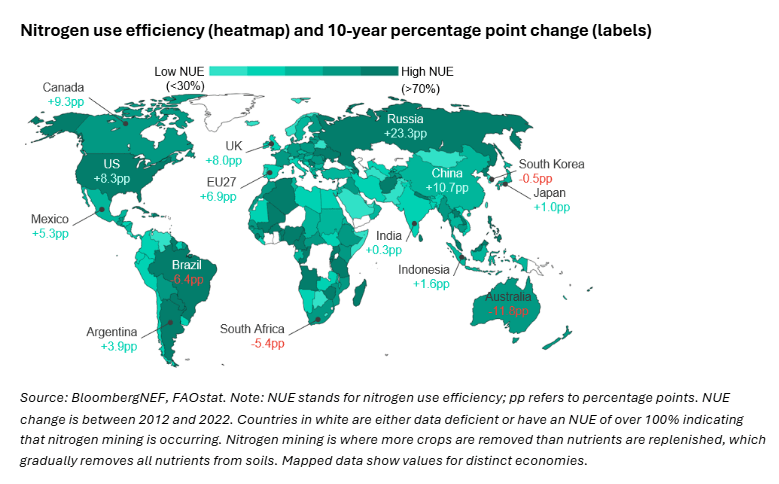

Both fertilizers and pesticides are being used more efficiently by farmers. Global nitrogen use efficiency – a measure of nutrients taken up by crops versus the total applied – has increased 6 percentage points over the last 10 years, and farmers are using 54% less chemical pesticide per dollar of agricultural output than in the 1990s. At the same time, the biological inputs market is expanding, and green fertilizer capacity pipeline is growing.

Nitrogen use efficiency is rising in regions where adoption of variable-rate fertilizer technology is high – including the US, Canada and the European Union. Farm machinery dealerships are increasingly offering a broad suite of precision agriculture services. Around 90% of US dealerships have offered variable-rate fertilizer delivery technology since 2020.

Lack of investment and interest

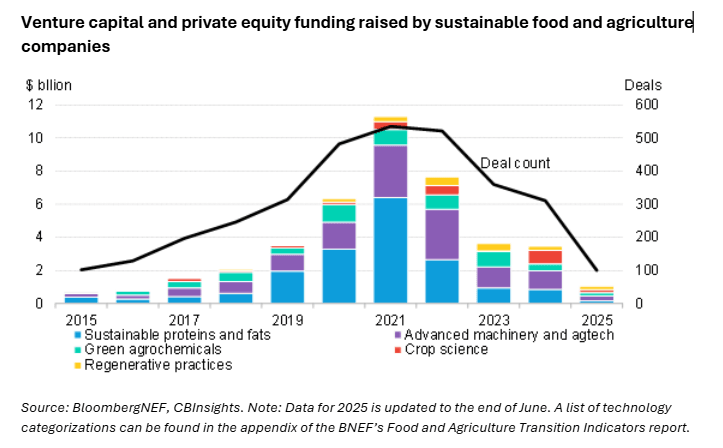

Off the farm, earlier signs of progress have reversed. Venture capital and private equity fundraising by sustainable food and agriculture startups has collapsed since its 2021 high and agricultural carbon offset markets are in a state of torpor. At the same time, several agri-food companies have scaled back or abandoned initiatives and targets, including Unilever and PepsiCo’s U-turn on sustainable packaging. Clean energy procurement and electric transport target-setting by food and beverage companies has also stalled.

Alternative proteins have failed to tantalize tastebuds. Investment in the sector is down 87% from its 2021 peak and plant-based meat retail sales continue to slide. Meanwhile, policymakers are shunning lab-grown proteins: seven US states now ban the products with another six pending. But in the background, consumers are gradually shifting away from high-emissions red meat to consume more fish and chicken.

Signs of distress

The agricultural system is displaying climate vulnerabilities: coffee and cocoa crops are failing, the spread of avian disease is persisting, and droughts are leading to a surge in insurance issuance and claims. In short, weather and water stress is reshaping how, where and at what cost food is produced.

Global mean surface temperatures reached a record 2.118 degrees Celsius above the 1951-1980 baseline in 2024, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. The last 10 years were the warmest 10 years on record. Recent climate predictions, including those from the World Meteorological Organization, expect global land temperatures to remain at or near record levels in this year, though weather models disagree on return of La Niña in 2025.

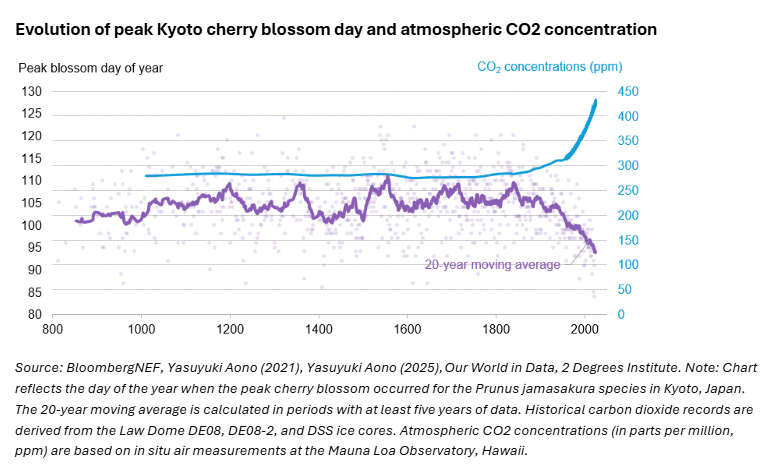

Higher temperatures affect the length of growing seasons and accelerate crop maturity. Kyoto’s cherry blossom data, one of the longest empirical climate indicators in existence, reached new records in 2025. The 20-year moving average shows blossoming occurring on the 93rd day of the year, 14 days earlier than the moving average two centuries ago. The timing of flowering is linked with warmer temperatures at the onset of spring. In 2025, the peak cherry blossom occurred on April 4, the 94th day of the year.

Continued drought conditions in the US are contributing to elevated crop insurance payouts to the grains and oilseeds sector. Similarly, a record number of livestock insurance policy issuances indicate that farmers are increasingly uncertain of their revenues under climate stress.

Despite these signs, few seed companies are bringing new climate-resilient or pest-resistant crop strains to market. In 2024, more than 600 new broadacre crop strains were patented, but only 1% of innovations were related to a more resilient strain. Patent registrations suggest that seed companies are instead focused on developing strains with improved grain quality or yield.

BloombergNEF clients can access the inaugural edition of BNEF’s Food and Agriculture Transition Indicators here. The series will provide an annual update on the state of the transition.