By Michael Liebreich, Senior Contributor, BloombergNEF

It is seven months since Donald Trump was swept back to the White House in the US presidential election. Already the scale of Trump’s ambition to turn back the tide of clean energy and consolidate the U.S. dependency on fossil fuels has been made clear. And it is finding resonance around the world.

Those who would build a clean energy future face a choice. They can either double down on their old narratives, press on with existing plans, and preach largely to the converted. Or they can refresh their offer. They can wind back historical over-reaches, address the legitimate concerns of voters, and come out fighting.

I am going to make a strong case for a pragmatic climate reset in this first part. In Part II, I will lay out what it might entail. First, however, we need to have a conversation about where we are. With so many pundits and politicians explaining that the energy transition is nothing but a dream that is doomed to fail.

I’m also going to explain why they are wrong, and why rumors of the death of the transition are greatly exaggerated.

The troubling Troubled Transition

In February, veteran fossil industry advisor Dan Yergin and two co-authors published a piece in Foreign Affairs called The Troubled Transition. In it they dismiss the idea that there is or can ever be an energy transition, anchored on the fact that fossil fuels contributed 85% to so-called primary energy in 1990 and still contribute 80% today.

Needless to say, their argument has been widely amplified by the oil and gas industry. For instance, in his remarks at the industry’s CERA Week conference in March, chaired by Yergin, Saudi Aramco Chief Executive Amin Nasser joked that “there is more chance of Elvis speaking next than the current plan working.”

Well, through the wonders of AI, here’s Elvis.

Delve below the surface, and it’s easy to see what the authors of The Troubled Transition are doing. The apparent stasis in fossil fuel dependency, of which they make so much, conflates periods with dramatically different trends. Between 2000 and 2010, China’s coal use surged by 130%; between 2015 and 2025, by contrast, wind and solar soared – so much so that these two technologies now meet 17% of global power demand.

So, while overall fossil dependency may have declined only marginally, any forecast based on projecting out the global figures would clearly be misleading.

Yergin and co. would have us believe that new energy technologies are only ever additive. Someone should tell the whale-oil, town-gas and marine-coal industries. In fact, in order to believe the “additivity” theory, you have to believe that increased use of hay, firewood, charcoal, peat and animal dung in the developing world is causally linked to their decline in the OECD. Global energy trends are actually made up of wildly different trends in different parts of the world. A heuristic that says new energy technologies can only ever be additive is worthless – except, of course, to fossil-fuel companies.

Yergin and co. play several other games. They promote the so-called primary energy fallacy, by which the world’s apparent dependence on fossil fuels is inflated. The real figure is not 80% but 68%, because of the differential inefficiency of fossil fuels compared with clean energy, which is also missed by Lomborg, Smil, US Energy Secretary Chris Wright and others (See Superhero Number 5 for more on the primary energy fallacy). If you think the difference between 68% and 80% is not that important, think about the difference between clean energy meeting 32% or of 20% of demand – instead of one fifth of energy demand being met by zero-carbon sources, it’s already one third. The transition is considerably more advanced than its detractors would like us to believe.

Yergin and his co-authors continue. They confuse investment in clean energy with cost. They compare apples with pears by ignoring the investment requirement of a purely fossil-based counterfactual. They gaslight proponents of climate action by pretending they are fundamentalists, interested only in achieving global net zero by 2050.

Most cynically, they fail to acknowledge that ever-growing atmospheric CO2 means ever-increasing economic impacts of climate change, including severe damage to the coastal and offshore fossil fuel installations owned by their clients.

They conclude with a demand for a new approach – which they call a “pragmatic path”. Pragmatism is needed, but not the pragmatism of defeat. Not the ‘pragmatism’ of believing fossil fuels hold the key to further human progress. Not the ‘pragmatism’ of addressing climate change only if it suits the interests of fossil-fuel companies.

What is needed is the pragmatism of robust but affordable climate action.

The non-linear transition

A second narrative of failure comes from Michael Cembalest, chairman of market and investment strategy group at JPMorgan Asset Management. In his 15th annual Eye on the Market Energy Paper, he acknowledges some progress on cleaning up the energy system, but decides that “after $9 trillion spent globally over the last decade on wind, solar, electric vehicles, energy storage, electrified heat and power grids, the renewable transition is still a linear one, slowly advancing at 0.3% to 0.6% per year.”

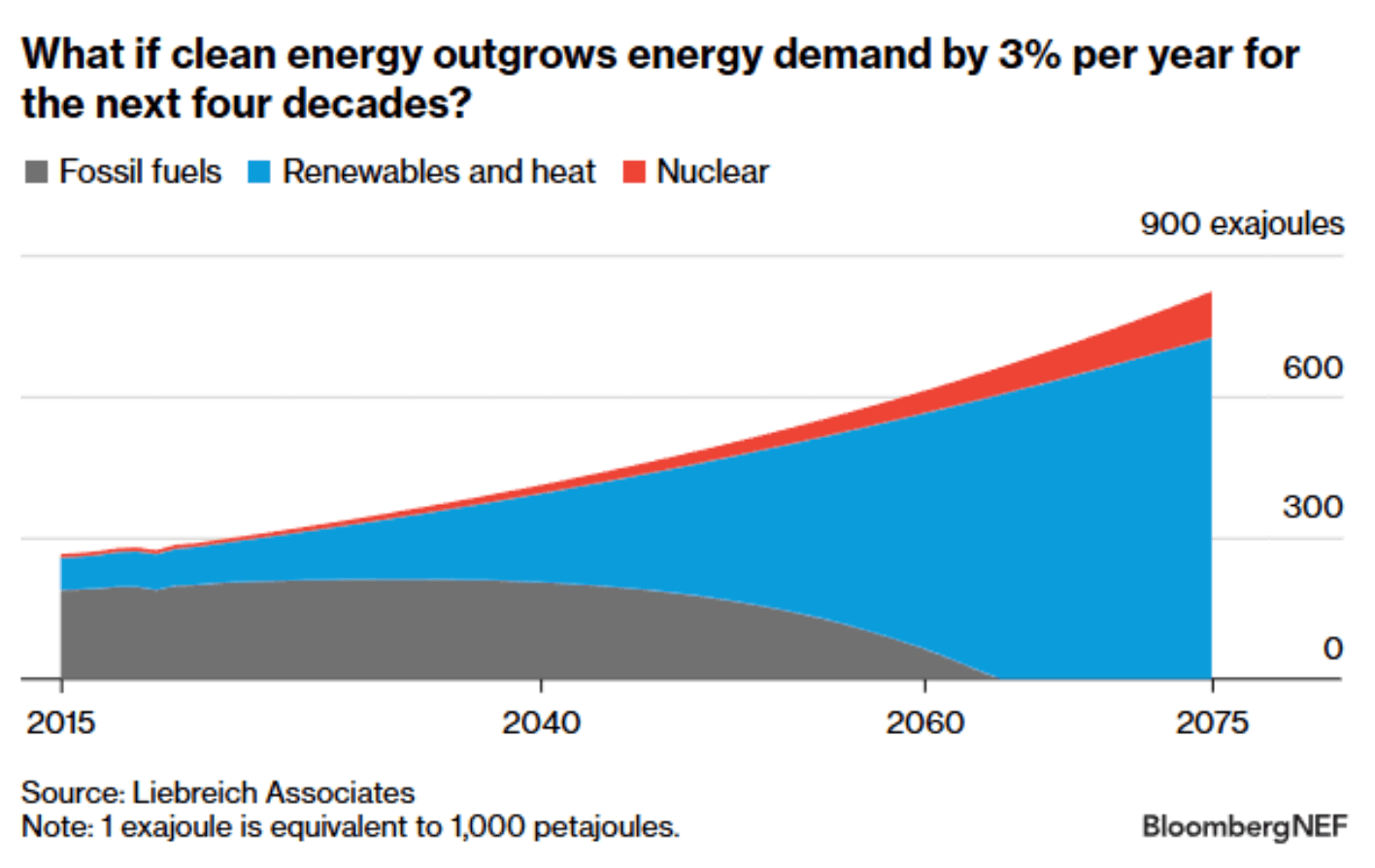

This is a bad miss for a usually excellent analyst. To see why, we can use a very simple model, requiring only a four-line spreadsheet, and explore what happens as clean energy continues to outgrow overall energy demand for a few more decades.

Let’s start with the global economy, which has been growing at 3.3% per year since the year 2000. Let’s assume this continues into the future. Next, we assume that the historic 1.3% average annual improvement in demand-side energy efficiency continues too, leaving 2% annual growth in demand for energy. We’ll be using real energy demand, not primary energy, which is really a measure of supply.

Now let’s assume clean energy, so renewables, nuclear, and the ambient heat used by heat pumps, start at today’s 30% and averages a conservative growth rate of 5% per year over the coming decades, considerably lower than the historic growth rate in renewables over many decades.

Finally, we’ll let fossil fuels make up the gap between total energy demand and clean energy provision, as it does in the real world.

The first thing our simple model shows is that despite growing faster than energy demand, clean energy is not yet able to meet all the additional demand for energy. But let’s run our growth rates out into the future and see what happens. For the next ten years, fossil fuel use continues to grow, falling as a percentage of energy use, but only from just below 70% to just below 60%. Clean energy continues to struggle to meet additional energy demand until 2035. Boo, failure: growth is linear and slow!

However, roll the clock another ten years. By 2045, with clean energy continuing to outgrow energy demand by 3% per year, fossil fuel use drops below where it was in 2025, though only by 8%. By now the global economy is using nearly 50% more energy than today, just as all the models say it will, but sourcing less than half of it from fossil fuels.

Another decade forward, and by 2055 fossil-fuel use has dropped by 40%, so it is now meeting less than one quarter of energy demand. And by 2065, fossil fuels have been squeezed entirely out of the system.

That said, in reality growth in clean energy won’t be 5% every year. It will start higher and then drop away as the sector matures. And there will be a tail of obstinately hard-to-abate fossil-fuel use. However, what the exercise shows is that in any scenario in which clean energy grows faster than energy demand over a number of decades, fossil fuels are squeezed out of the system.

It is worth noting that our little model generates a quite different trajectory to the vast bulk of the net-zero literature. It doesn’t deliver the large initial drop in fossil-fuel use – 45% by 2030, or whatever – that activists want to see, followed by a long tail. Emissions stay higher for longer, but then fall away, delivering an outcome broadly consistent with the 2°C of warming that lies at the heart of the Paris Agreement (though perhaps needing a little carbon dioxide removal in the second half of the century).

Our simple four-line model shows that the failure so far to see dramatic reductions in fossil-fuel use says nothing whatsoever about whether or not we are on a pathway to net zero. All the transition requires is a growth rate in clean energy that remains a few percent above the growth in energy demand for long enough – an approach which is much more plausible than walking away from our existing energy infrastructure.

The non-pragmatic reset

This brings me to Tony Blair’s piece. Two days before UK local elections in April, with Nigel Farage’s hard-right Reform party promising to “make net zero the new Brexit”, the Tony Blair Institute released a report entitled The Climate Paradox: Why We Need to Reset Action on Climate Change, with a foreword by Tony Blair.

Now, Blair is spot on in calling for a reset – I was intending to do exactly that in this column before he beat me to it – but his proposed solution is pretty much the opposite of pragmatic.

Blair opens his foreword to the report by pointing to the “irrationality” of the current debate over climate change, explaining that people are “turning away from the politics of the issue because they believe the proposed solutions are not founded on good policy”. To build a burning platform from which to propose his reset, Blair paints a dramatic picture of the failure of past climate action, repeating many of the talking points of Yergin and Cembalest, falling into the primary energy fallacy, and presenting a set of “inconvenient facts” curated to show the futility of the current pathway.

However, many of Blair’s “inconvenient facts” are either not facts, or are misconstrued. For instance, he makes much of China last year beginning construction of “95 gigawatts of new coal-fired energy, which is almost as much as the total current energy output from coal of all of Europe put together.” Construction starts are not the same as completions – the fact is that for each of the past five years China completed construction of 34GW of capacity and retired 2.5GW. A lot but not 95GW.

And capacity is not “energy output” The capacity utilization of China’s coal-fired power stations, how much they are really used, had dropped from more than 60% in the year 2000 to just over 50% in 2020. The surge in gas prices coming out of Covid and as Russia invaded Ukraine pushed China back to coal, but if gas prices ease further, we should expect the so-called capacity factors of Chinese coal plants to plummet again, and many older power stations to be shuttered. Indeed, recent data already shows China’s coal use falling over the past 12 months.

More of Blair’s “facts” are not facts at all, but forecasts. He says urbanization will continue in developing countries (he doesn’t mention it is coming to an end in China), and that Africa will see a doubling of its population over the next thirty years. I hope energy supply does soar in the Global South in coming decades. What the facts show, however, is that these new economic powers are leapfrogging to a far cleaner energy mix than other regions at the equivalent stage of development. They are investing in renewables, with exponential growth in Chinese solar panel imports, and in gas, not coal.

However, where Blair’s reset really hits the buffers is in its choice of solutions. Having stated that “net-zero policies, once seen as the pathway to economic transformation, are increasingly viewed as unaffordable, ineffective, or politically toxic,” he hangs his reset on the world’s most unaffordable, ineffective and politically toxic solutions.

The first hint of this is in the picture on the report’s front cover: It’s Climeworks’ Mammoth direct air capture (DAC) plant in Iceland. Whatever the solution to climate change is going to be, it won’t involve anything that costs $1,000 per metric ton of carbon removed, or even the $400 to $600 the company promises by 2030. In fact within a month of the publication of Blair’s call for DAC to be at the heart of his climate reset, it was reported in the Icelandic press that Climeworks plants had not even captured enough CO2 to cover emissions released during their construction. Embarrassing.

In fact, Blair goes big on all sorts of carbon capture and storage (CCS). “At present,” he asserts, “carbon capture is not commercially viable despite being technologically feasible – but policy, finance and innovation would change this.” Really?

What does carbon capture being commercially viable even mean? Clean energy solutions are commercially viable when they are cheaper than their fossil equivalents. However, CCS costs money to build, money to maintain, and money run. Unless you are selling the captured CO2 to extract more oil (in which case your project is a huge self-licking ice cream from a climate perspective), the only revenue is from abating emissions.

So CCS can never be “commercially viable” in the absence of voluntary markets for carbon abatement – which don’t and won’t exist at anything like climate-saving scale – or a regulatory framework that prices in the cost of carbon. That means you can forget the Global South, whose emissions growth Blair says he’s most concerned about. Even where there is a carbon price, it is far from clear that “policy, finance and innovation” would result in CCS cheaper than the entire gamut of clean energy solutions, especially in the light of the decades of failure of the former, and the decades of rapidly falling cost of the latter.

We will have to do some CCS. We will need it to capture emissions from industrial processes like cement production and aluminum smelting, to make affordable clean hydrogen (hydrogen from natural gas with CCS will remain cheaper than green hydrogen) and to sequester biogenic carbon to cover sectors where abatement is much more expensive, like aviation. But post-combustion CCS on large gas and coal plants will never be close to “commercially viable”, so putting CCS at the heart of a climate plan is a huge self-own.

The other big technology Blair promotes is nuclear: “The new generation of small modular reactors [SMRs] offers hope for the renaissance of nuclear power, but it needs integrating into nations’ energy policy.”

Apart from the fact that SMRs already lie at the beating heart of many nations’ energy policies, the problem is they offer exactly that: Hope. I’m as big a fan of nuclear power as it is rational to be (I studied it early in my career) but seventy years after the promise of “electricity too cheap to meter”, it is surely time to stop hoping for miracles. As I wrote in my Power and Glory piece on AI, you should be highly skeptical anyone claiming power prices below $180/MWh from a first-of-a-kind SMR, or below $120/MWh from an Nth-of-a-kind plant, where N is less than 10.

As a potential contributor to climate action, however, the biggest problem with SMRs is not cost, it’s numbers. Last year, wind and solar generated 4,600 terawatt-hours of electricity globally. To match that with 300MWe SMRs like those being designed by GE-Hitachi or Westinghouse, you would need to build 1,960 of them. Alternatively, you could build 1,250 Rolls Royce SMRs, each producing 470MWe. Or over 8,000 smaller units like those promised by Oklo and Kairos.

By the time you are done building those, say in 2050, you will be meeting less than 10% of global electricity and less than 5% of total energy demand. Wind and solar will be ahead by a factor of three or more, possibly much more.

To make any sort of dent in global emissions, you would need to build not just thousands but tens of thousands of SMRs – each of which requires permits, customers, fuel, security, trained staff, and so on. In the real world, we will be lucky to see half-a-dozen SMRs by 2030, and perhaps a few hundred by 2040.

Where does this leave us?

So, let’s summarize. We are at or near peak emissions. We have seen coal use plummeting across the developed world and starting to drop in China. We have seen the cost of wind and solar decimated, so they now make up 93% of new capacity added to the grid worldwide. We have seen EVs accelerate from a standing start to make up one car in every five sold worldwide, and one in two in China.

We are not on track to keep temperatures to 1.5°C, but we have seen that 2°C is still on the table, as long as we think like a tortoise, not a hare.

And yet, as Tony Blair points out, we have seen the fracturing of the consensus behind climate action. It has fractured completely in the US, has been rescued from the brink in Canada and Australia. It is under severe strain in the UK and is showing signs of cracking across Europe.

We do need to recalibrate. Continuing to insist on technological purity and policies that drive up costs, especially for the poor and vulnerable, is not a viable plan. Not any more.

What we need is a Pragmatic Climate Reset. In Part II, we’ll look at what that might entail.