By Vandana Gombar, Senior Editor, BloombergNEF

Hydropower generates more electricity than all other renewable technologies combined and took a major step forward last year with as much as 34 gigawatts added. But one of its top proponents wants a bigger leap, especially to balance the increasing role played by intermittent renewables solar and wind.

“There are really no practical alternatives,” Malcolm Turnbull, the former prime minister of Australia and the president-designate of the International Hydropower Association, said in an interview. “We need a dramatic growth in hydro power.”

Asia’s leading the way, accounting for most of the 130 gigawatts of hydropower plants being built. The share of pumped hydro plants, where water is pumped up into a reservoir at times of surplus power and used to generate electricity during heavy demand, is rising. If the speed of development doesn’t pick up, though, Turnbull sees unwelcome consequences.

“Without hydropower we will either fall back on fossil fuels … or we will have system instability including, ultimately, blackouts.”

Turnbull backed the Snowy Hydro 2.0 pumped hydro project in Australia which has been hit by cost and time overruns. It is now expected to cost A$12 billion ($7.65 billion) with full power generation capacity of 2.2 gigawatts expected by December 2028 at the earliest.

Building a hydropower project can take five to 10 years once all the necessary permits are secured, itself a major challenge.

Turnbull highlights the need for “political will” so that projects can move quickly. “If we want to achieve net zero, we must prioritize including hydropower in energy strategies and streamline permitting,” he said, arguing that the triumvirate of solar, wind and hydro can provide 24×7 clean power.

But how clean is hydro power?

He cited numbers from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC: the median lifecycle emission intensity of hydropower worldwide is 24 grams of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt-hour. That compares to 11gCO2e/kWh for onshore wind, 48gCO2e/kWh for solar, 490gCO2e/kWh for natural gas, while coal comes in at 820gCO2e/kWh.

Turnbull is currently a senior adviser to KKR, a role he intends to continue after officially taking over at the IHA next month.

The following Q&A has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

At this point in 2023, there are multiple positive developments in clean energy– the US Inflation Reduction Act, growth in wind and solar, a rising number of electric vehicles. But are they going to fall short in addressing the sheer scale of the climate challenge?

Global warming is the single biggest existential threat to life on earth as we know it. We have got every resource to deal with this challenge except one, and that is time. You know time is running out. We have the tools to effect a transition to zero emission energy. We have abundant opportunities for wind and solar, and the cost of both is continuing to decline. But they are intermittent and therefore you need a firming capacity. Hydro provides the ability to deliver zero-emission dispatchable power. There are really no practical alternatives to that.

Pumped hydro has enormous advantages as well. It has been a big part of my agenda when I was prime minister, and I am still very involved in that sector. We really cannot get to net zero without hydro. Hydropower has to be sustainable – that is clear – but you can make that point about every technology.

As you know, hydro is the largest source of renewable energy in the world at present. It is about 17% of global electricity production – about the same as all the other renewable sources of generation combined. We need a dramatic growth in hydro power.

Do you consider hydro zero-emission power?

Hydropower assets have a very long lifespan, typically in the order of 100 years, meaning that emissions associated with construction can be amortized over a much longer time. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2014) states that the median lifecycle emission intensity of hydropower worldwide is 24 grams of CO2 equivalent per kilowatt-hour. The median figure for onshore wind is 11gCO2e/kWh, solar energy is 48gCO2e/kWh, natural gas is 490gCO2e/kWh and for coal is 820gCO2e/kWh.

Do you think the world has woken up to the urgency of the climate crisis?

The answer is yes, but there are all too often more immediate pressing concerns. You’ve got a number of things going on, like that movie Everything Everywhere All at Once. In some developed countries, particularly the US and Australia, there has been concerted action by the fossil fuel sector that opposes the transition to clean energy and has been supported by a populist right-wing political agenda which has sought to turn global warming into an ideological issue.

Saying that you believe or disbelieve in global warming is about as sensible as saying you believe or disbelieve in gravity. We have to stop addressing this problem with what I used to call ideology and idiocy, and focus on engineering and economics. You’ve got to replace coal (and other fossil fuel)-fired generation with renewable generation. Hydro has a central role in firming variable renewables. For long duration storage, it is really hard to beat hydro. In fact, I don’t think you can.

There is a tendency for people who want to oppose the transition to say: We have to wait for new technologies. I have described this as a form of environmental Micawberism. Mr Micawber in David Copperfield [by Charles Dickens] was always hoping “something will turn up.” The truth is we have the tools to do the job today. There are very few countries that cannot deliver enough primary generation from a combination of wind, solar and hydro. These three working together can give you 24×7 clean power but you have to plan it.

If we are building reservoirs and pipelines and power stations on the mountains – these are assets that will last for hundreds of years. They are kind of permanent infrastructure, but you have got to get cracking, and it takes time. That is why I got started with the big pumped hydro scheme in Australia – Snowy Hydro 2.0 – which is under construction at the moment. We need a lot more of them.

What do you hope to achieve at the International Hydropower Association?

I got involved with the IHA because I regarded the lack of provision of long-duration electric storage as the ignored crisis within the energy crisis. We are rolling out lots of wind and solar everywhere – which is great – but unless you have the ability to firm that, you haven’t got a solution.

We went through this in South Australia in 2016 – that was a big wake-up call. South Australia had deployed an enormous amount of wind in particular, and a number of coal-fired power stations were closed down. Some storms occurred, wind farms went offline, transmission lines went down, and the state went into a blackout. This wasn’t a matter of renewables being unreliable. It was just that you need to plan it. We need to get back to engineering and economics. If you are going to close a 2,000-megawatt coal-fired power station, you’ve got to make sure that you are able to replace that dispatchability. The International Hydropower Association advocates for the global development of sustainable hydropower to fill the hole left by coal.

What are your views on nuclear power?

I am not against nuclear power, but it is very expensive. It also has huge environmental risks. You can’t wish away Fukushima or Chernobyl. The risks are real, and the public sees them as real, or why is Germany still decommissioning its nuclear power plants?

Every technology has its challenges. Hydro, for example, must deal with times of low or high river levels, especially with climate change raising the risk of sudden floods. In Norway, a dam wall collapsed recently.

I agree with you. Nothing is without problems. I am not anti-nuclear. I am just saying that nuclear doesn’t actually address the challenge that we have of making variable renewables reliable. If you assume that your cheapest form of primary generation is going to be wind and solar, then the technology you need is a firming technology that is variable and dispatchable. Nuclear is not, because nuclear power stations run all the time. Pumped hydro complements nuclear power stations.

Obviously, issues of dam safety are primary. However, please note that hydropower dams are often multipurpose and can play a crucial role in flood prevention to protect local areas from flooding. Recent IHA analysis found that globally an annual saving of $53-96 billion can be attributed to the flood control function of dams.

On the question of water availability and drought, one of the attractions of pumped hydro is that it doesn’t actually need a lot of water. You certainly don’t have to dam valleys. If for example, you have 10 million cubic meters of water – 40 hectares at 25 meters average depth or 50 hectares at 20 meters average depth – with 400 meters of elevation, you will get 700 megawatts for 10 hours. That small reservoir is a big battery. With pumped hydro, you don’t need a huge amount of real estate. Building dams on top of hills is not easy – you’ve got to get the right topography and you’ve got to make it safe – but it’s not like putting a dam across a river and flooding thousands and thousands of hectares of land and ecosystems and moving villages and towns.

The IHA’s sustainable hydropower declaration of 2021 says that “going forward, the only acceptable hydropower is sustainable hydropower”. The Hydropower Sustainability Standard was launched two years ago and is certifying projects all around the world against a rigorous set of requirements set up governments, NGOs, banks and companies together.

The last IHA report (July 2023) says that annual average hydro capacity added over the last five years is 22GW, which is less than half of what is needed to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. What is the share of pumped hydro?

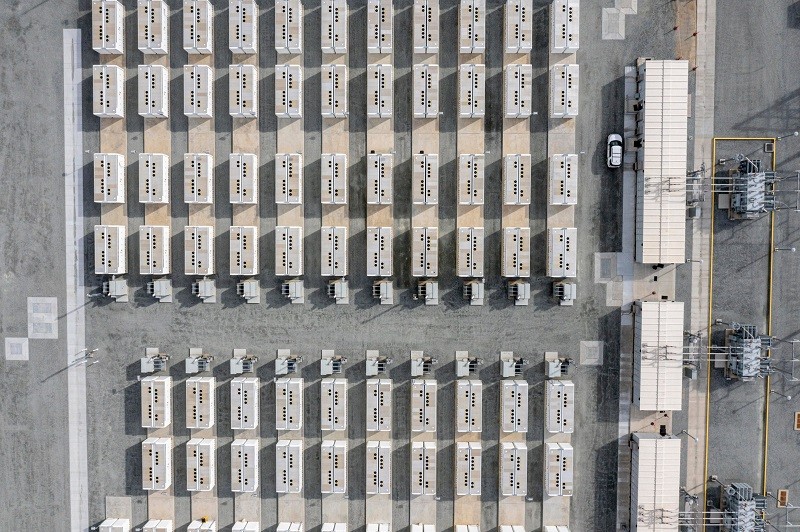

In 2022, 10.5 gigawatts of pumped storage hydropower were commissioned globally. That is part of a long-term upward trend.

What is priority number one to increase annual build?

Political will. Projects can proceed quickly with proactive government interventions (e.g., China and now Australia and India to a lesser degree). If we want to achieve net zero, we must prioritize including hydropower in energy strategies and streamline permitting.

What’s the average time needed to develop a hydro project, from approval to commissioning?

It is obviously very different in different countries, but once a project receives the appropriate funding, planning and regulatory permitting, they take between 5-10 years to build and commission.

Does that not, realistically speaking, limit the role that hydro can play in curbing warming, or reaching net zero?

IRENA and IEA both estimate that the most cost effective, achievable global net-zero energy system will require around twice as much hydropower by 2050 as there is today to make net zero scenarios a reality. In other words, we need to build the same amount of hydropower in the next 30 years as in the past 130. The key message is that governments must plan for all types of renewable energy in their net-zero strategies now.

Which regions are on the right track? Are there lessons that can be scaled to other markets?

China has accounted for over two thirds of the new installed hydropower in the past decade. Pleasingly, other regions are picking up on this now. We have seen encouraging legislative progress in India, Europe, Central Asia, and the US, which gives me hope that we will see a hydro renaissance, especially for pumped storage, in the next decade across the world. In the pipeline, there is nearly 600GW of new hydropower projects, with 131GW under construction as of May 2023. As much as 78% of the pipeline is made up of projects that have been announced or seeking planning permissions.

Are sustainable hydro projects more expensive?

It costs more to not make a project sustainable. Developers should consider sustainability at the heart of their projects so that they are considering issues like labor and working conditions, biodiversity, indigenous communities, downstream flow regimes, benefit sharing, etc. at the start of their projects.

Hydro has been a challenging technology for private investors. What can be done to change that?

These are very expensive projects with very long lives and very often, that is the type of infrastructure that is built by governments. There are different approaches being taken around the world. In some places, governments are building it. In others they are providing underwriting or capacity payments to support the construction of long-duration storage. If you have an energy-only market – as we do in Australia – where you are essentially paid for the number of megawatt hours you dispatch, that doesn’t really deliver what you need to support pumped hydro or long-duration storage. You can make a business case for shorter duration storage in an energy only market – you buy at $40 and sell at $80, for example. With long-duration storage, you are asking your provider to essentially keep electricity in reserve – in other words, to keep a lot of water in the dam on top of the mountain – as insurance. The government or the market has to pay for that.

Communities often object to new hydro projects. What can be done to minimize the impact?

I have had a rule of three T’s – truth and transparency build trust.

The exciting thing about pumped hydro in particular is that it does not need a lot of real estate. The environmental impact of that is minimal. It is very efficient, and therein lies the opportunity.

What has been the biggest lesson from Snowy Hydro 2.0 for you?

It has been delayed. This happens. If you are going to build a project of this size, which involves 40 kilometers of tunneling, and expect that to go without problems, you are very naïve. They have had some problems with the tunnel boring machine. I think it is too early to say what are the lessons. The thing about Snowy Hydro 2.0 is that it is very sui generis – it is two enormous existing reservoirs that are 20 kilometers apart but with 700 meters difference in elevation, so the challenge is connecting them, because there is a large mountain between them. That is an opportunity to create a gigantic battery, and you can have Snowy 2, Snowy 3 and Snowy 4 even, but we need a lot more storage than that. The more conventional form of pumped hydro – with one reservoir at the top and one at the bottom – is not rocket science, but it takes time to build it and is costly, and we don’t have a lot of time.

If the world doesn’t warm to hydro, what are the risks?

The major international agencies (IEA, IRENA) have a simple answer to this. Without hydropower we will either fall back on fossil fuels, with all the climate and energy security risks they bring, or we will have system instability including, ultimately, blackouts.