The three pillars of the energy transition – wind, solar and battery plants – are becoming more efficient in their use of metals.

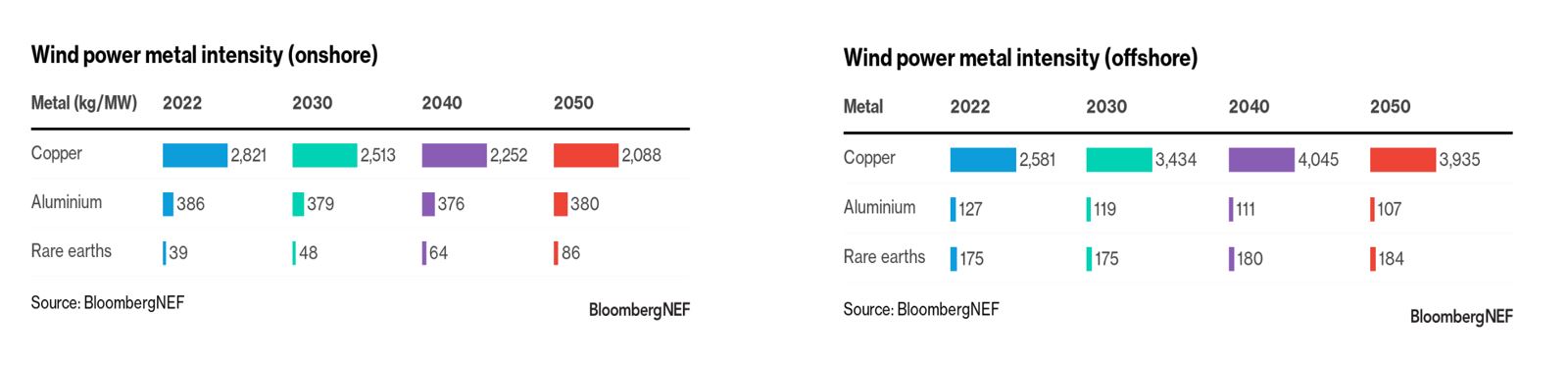

The amount of copper in an onshore wind farm, for instance, is set to fall by 10% to about 2,500 kilograms per megawatt by the end of the decade, according to BloombergNEF. Steel usage, meanwhile, could dip by 3% over the same time period to 150 metric tons. The projected declines in metal consumption are much sharper by 2050.

“The new generation of metals is enabling the next generation of renewables,” said Sung Choi, BNEF’s lead metals analyst in the US. “Metals are usually categorized as commodities but they are really specialized products that are improved constantly with new technologies.”

Lightweighting of metals has played a big role in development of electric vehicles, for example.

The trend is contrarian, however, in the offshore wind sector, where copper use per megawatt is rising. But so is the power generation capacity of each turbine.

China State Shipbuilding Corp. and MingYang have announced giant 18-megawatt offshore turbines this year. Outside China, the largest turbines are 15 megawatt machines, and these are big enough, according to the chief executive officer of Vestas Wind Systems Henrik Andersen.

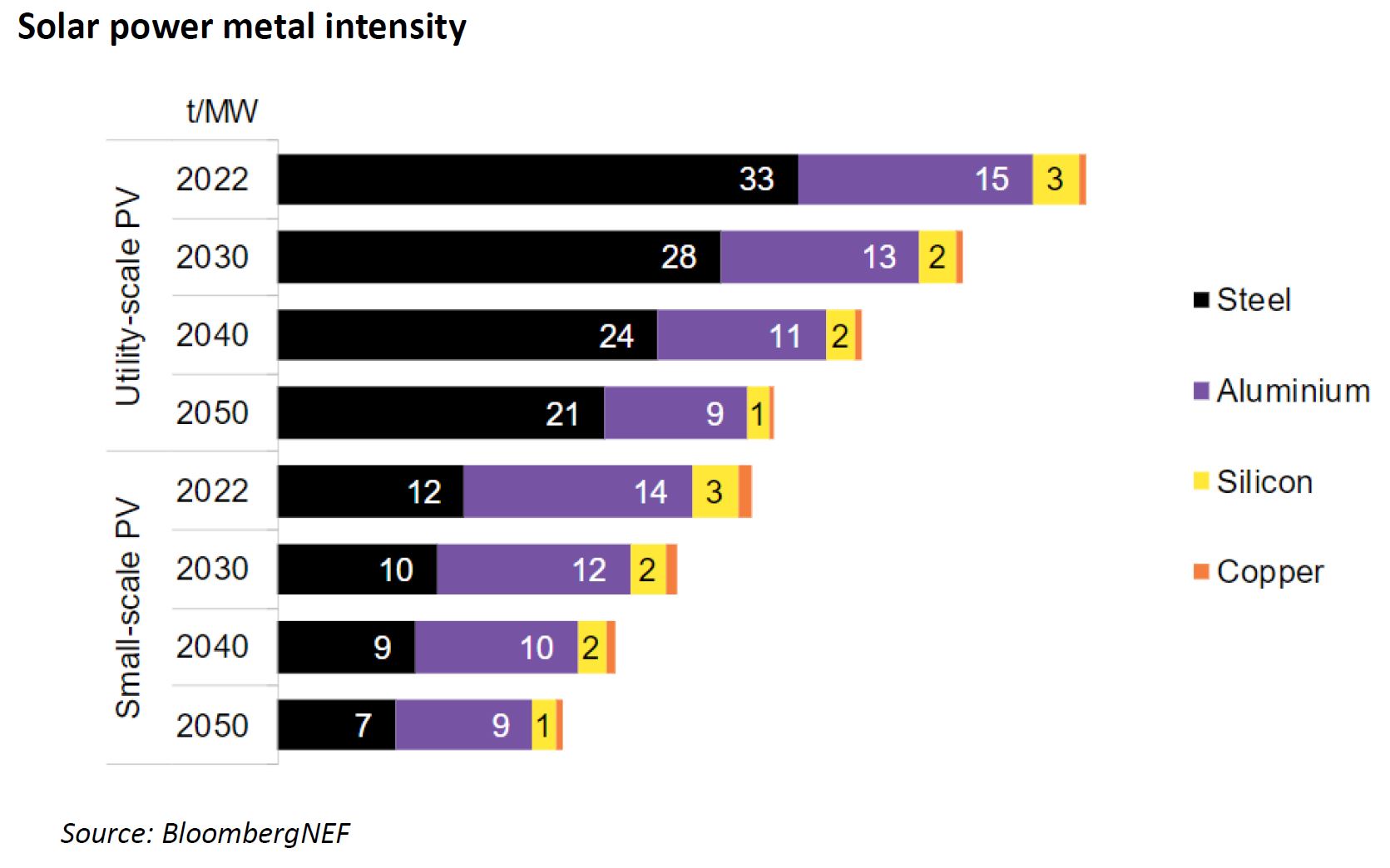

The intensity of metal use is also decreasing in large solar farms, as well as smaller rooftop plants, limiting a potential surge in metals demand.

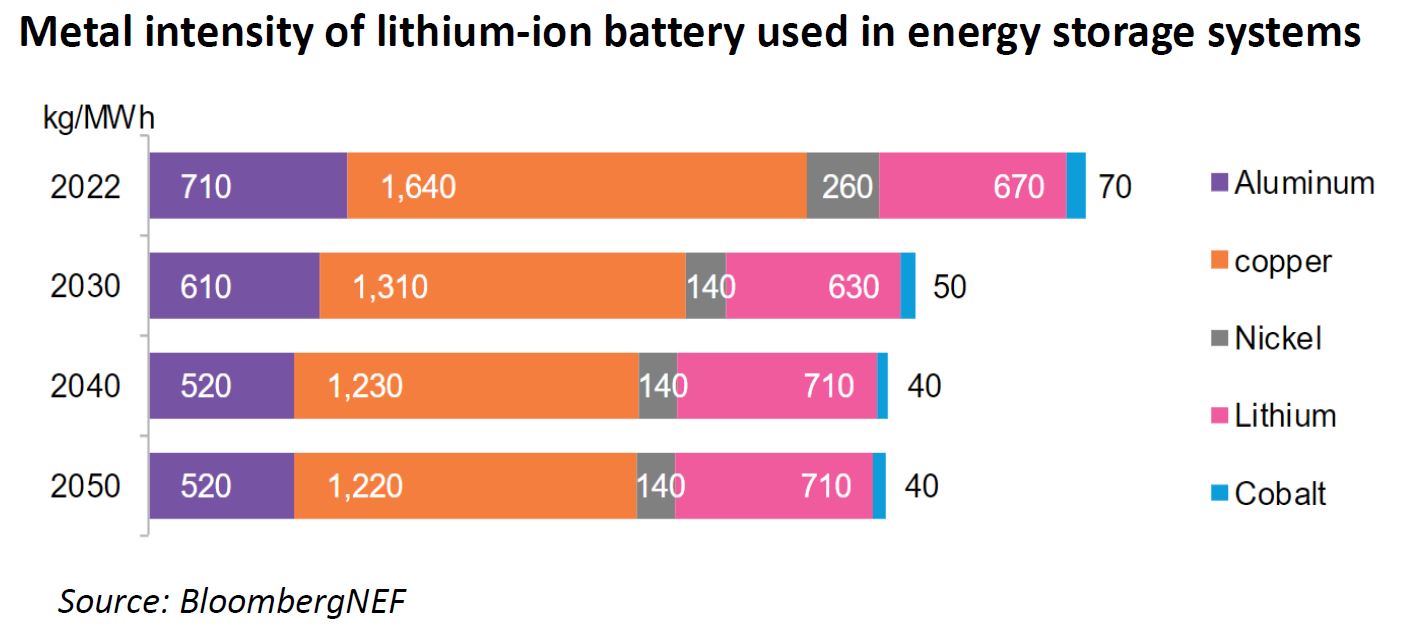

The metal intensity of a lithium-ion battery deployed in energy storage systems is expected to decline to 2030, though usage of lithium could rise in the subsequent decade, BNEF analysis shows.

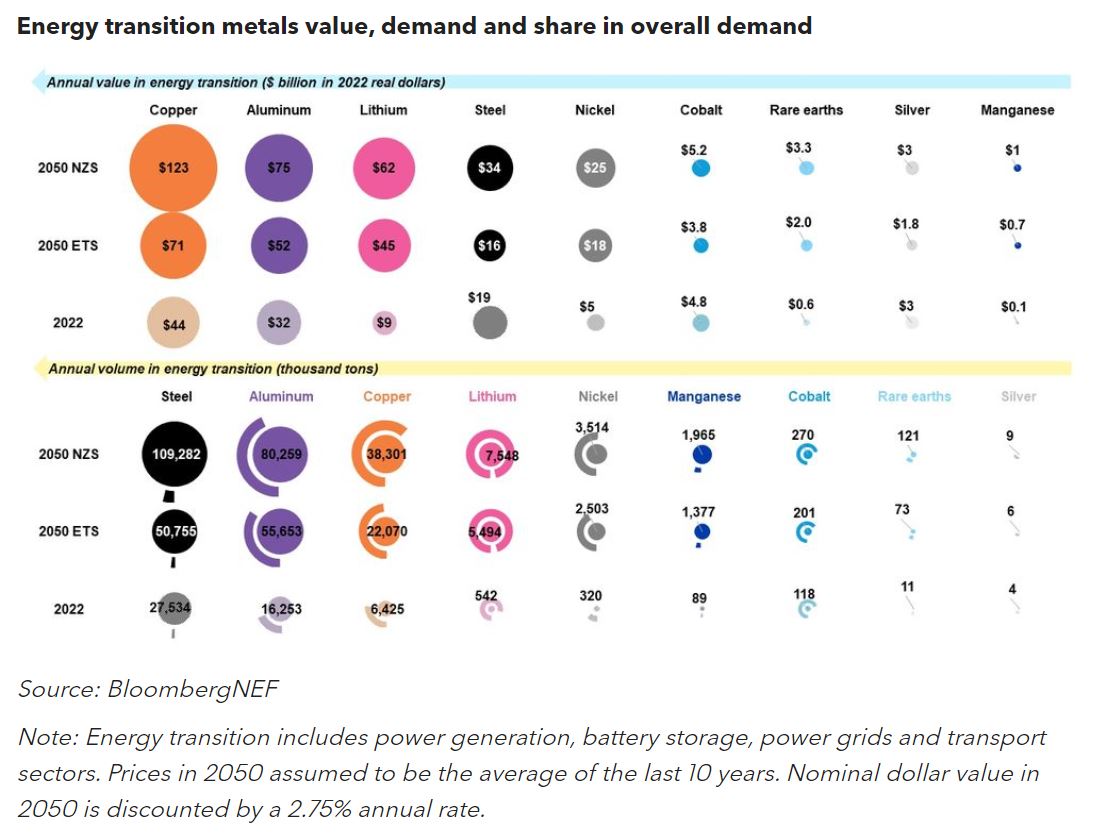

Nevertheless, the total volume of metals used in the next few decades will increase as the energy transition ushers in more clean power capacity and storage, and this could lead to a supercycle for the metals and mining industry. Copper, aluminum, lithium and steel are the four key metals powering the change.