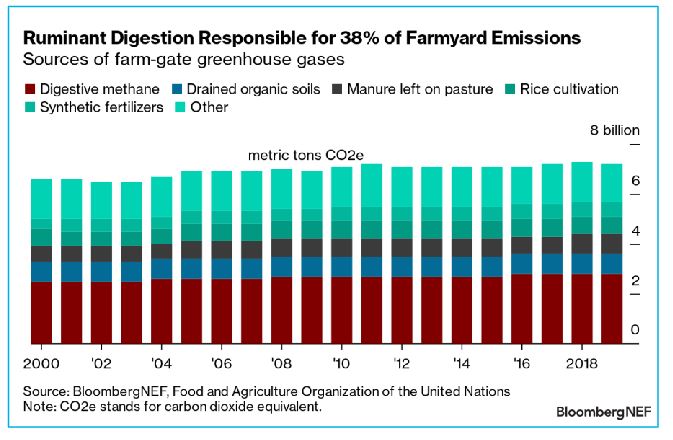

If a 12–year–old were to come up with a joke about climate change, it seems likely that cow burps would be part of the punchline. But there is nothing funny about digestive emissions from barnyard animals, which account for 38% of the greenhouse gases produced by farms. The pursuit of lower–carbon cow burps is turning into big business now.

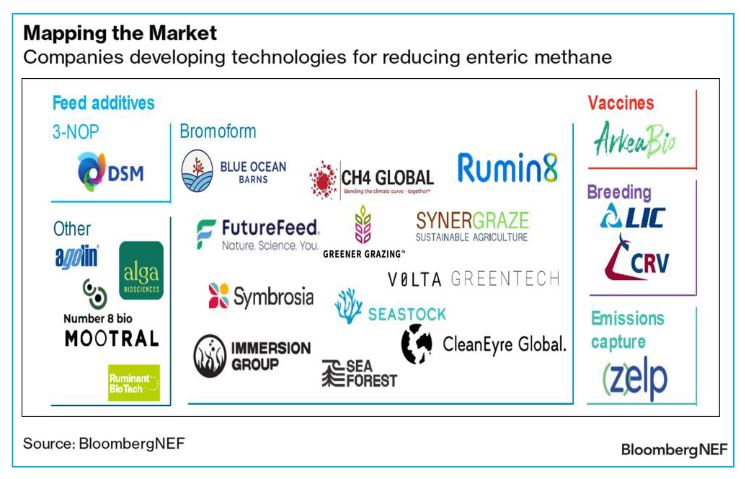

Startups looking to cut back on enteric methane – or methane produced as part of ruminant digestion – have raised $123 million since 2019. Investors include Breakthrough Energy Ventures LLC, Danone Manifesto Ventures, Elemental Excelerator, and Prelude Ventures. While a variety of technologies are under research, today, the most advanced method of interrupting digestive methane takes the form of feed additives, which account for as little as 0.5% of a cow’s diet by mass.

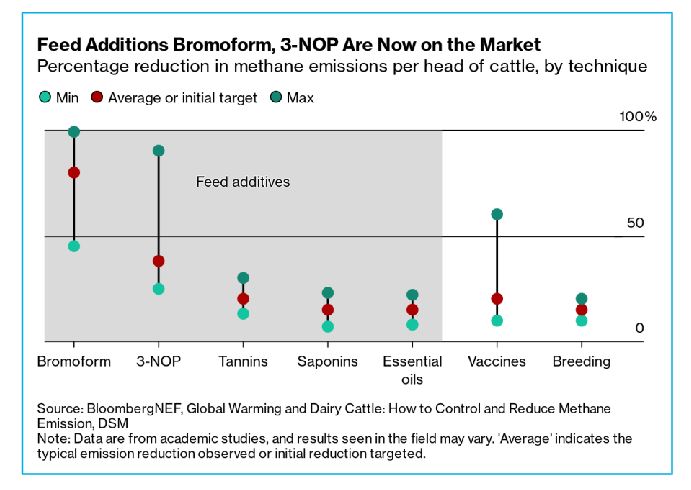

Startups and established agriculture companies are developing an entire bovine buffet of these methane–inhibiting additives. Already on the market is DSM’s 3–NOP (short for the chemical 3–Nitrooxypropanol), which has been approved for use in more than 45 countries and can reduce digestive methane emissions by as much as 45%.

Another promising option is bromoform, a feed additive derived from red seaweeds, that can reduce methane in burps by as much as 80%. Dozens of startups are growing the seaweeds commercially, and a handful of jurisdictions have approved its use already.

Other products at an advanced stage of development utilize essential oils and extracts of citrus and garlic. Scientists have identified over 90 potentially methane–busting feed additives including tannins, saponins and nitrates.

But why the focus on cow burps? Ruminant digestion makes up a third of the greenhouse gases coming from farming, or 2.8 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year. In other words, cutting back on barnyard methane could have a major impact on the climate.

“Fundamentally, we need to reduce red meat consumption in order to reduce emissions,” says BNEF analyst Stephanie Diaz. “But given that cows and other ruminants remain an important source of nutrients, any technology that can reduce emissions from these animals could have a significant impact on the climate.”

These interventions don’t come cheap. Using 3-NOP, it costs $70 to $80 to prevent one ton of carbon dioxide equivalent from entering the atmosphere, according to DSM.

It is also unclear whether consumers will be willing to foot this price premium for the sake of the climate. And even if climate-conscious consumers are willing – and able – to pay a price premium, a real scale-up in methane-busting feed additions might not happen quickly enough to turn the tide of climate change.

The road to deployment is still full of potholes.

“Additives currently on the market need to be given daily,” says Diaz. “This is easiest to implement in beef feedlots or dairy farms where humans interact with the cattle on a daily basis. That’s not necessarily the standard for cattle farming around the world.”

Transitioning feed additives from the research stage into widespread implementation will also require regulation and a scale-up in production.

“Changing cow burps is a long-term project,” Diaz says. “Feed additives have the potential to help in the short term, which is necessary and urgent, but they cannot eliminate the emissions entirely. We should hope for rapid adoption of these technologies once they’ve received regulatory approval, but that won’t stop us from needing to cut down on or eliminate red meat and dairy from our diets.”