By Vandana Gombar, Senior Editor, BloombergNEF

Batteries are the next big green investment opportunity, the co-head of climate strategy at Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., Emmanuel Lagarrigue, told BloombergNEF.

The first investment of the Climate Fund that KKR is finalizing was therefore a battery play: the UK’s Zenobe secured $750 million last year. Its other two investments so far are in US-based Avantus (solar, storage) and Spain’s Ignis (hydrogen).

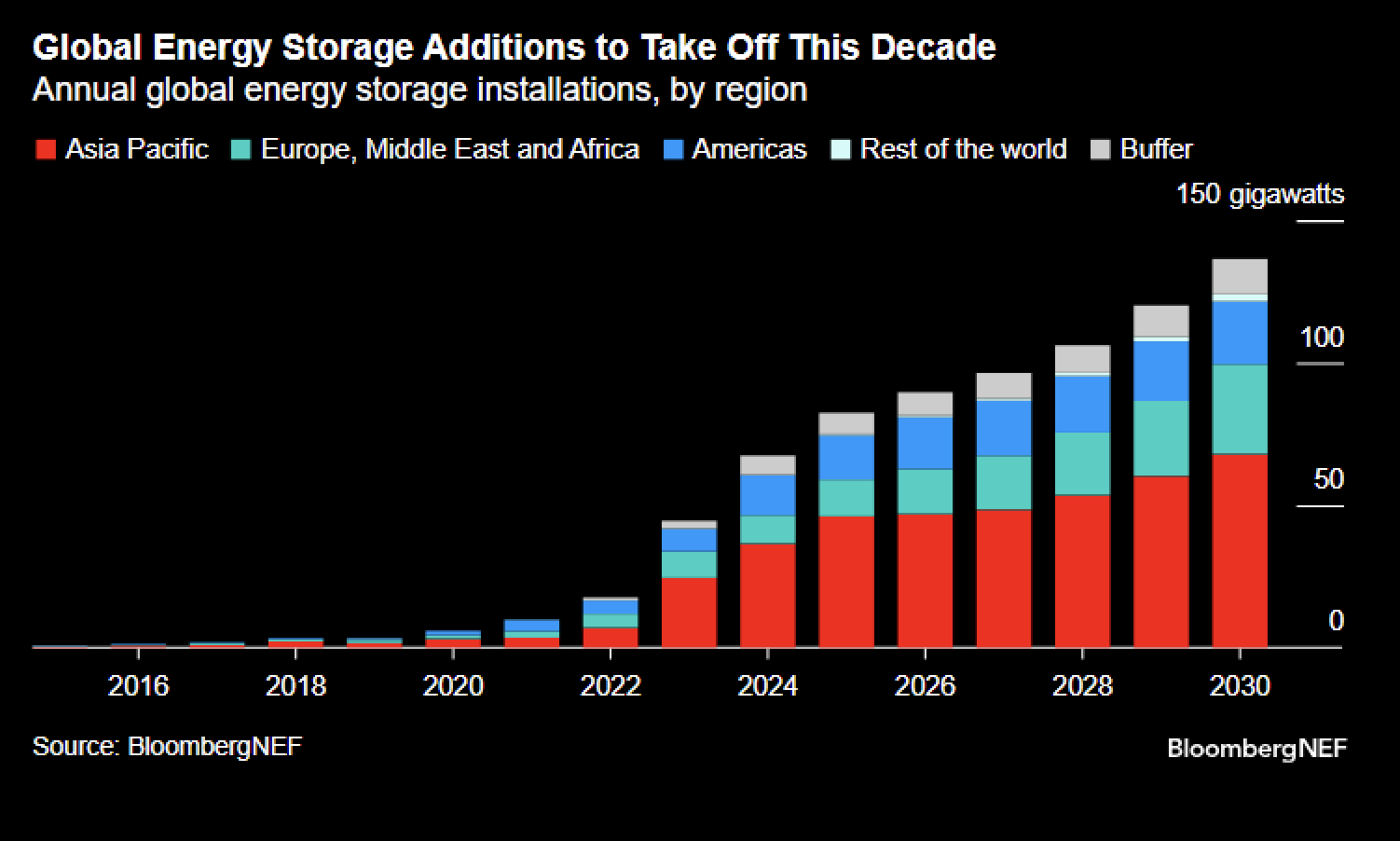

Batteries are critical to balancing a renewables-heavy grid as well as for electrification of transport. “It’s simply much easier to install a battery than to do a transmission line,” Lagarrigue said. “Just like solar and wind are today the bread-and-butter of many infrastructure funds, tomorrow it will be batteries.”

The US-based investment firm with more than $600 billion of assets under management embarked on a more climate-focused path about two years ago when it hired Lagarrigue (formerly with Schneider Electric), as well as Charlie Gailliot (Goldman Sachs) and Neil Arora (Macquarie). “Each one of us has more than 20 years of experience in decarbonization. It was a deliberate move of KKR to put us together to build a new [climate] strategy with the ambition to be the best and the first one to crack this,” he said.

KKR has already invested over $34 billion in climate and environmental sustainability solutions over the last 15 years. The idea now is to focus on emissions-intensive pockets – energy, transportation, costly-to-abate sectors like industry, buildings, data centers, food and agriculture – and countries with a lot of emissions, which means developed economies. “This is why most of what we do is 40% in North America, 40% in Western Europe and 20% in developed Asia, because that is where the emissions are,” he said.

Under the new strategy, KKR plans to invest $400 million to $700 million of equity capital on every deal, with a holding period of up to seven years.

Lagarrigue is optimistic about the world reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. Speed & Scale is one of his favorite climate-related books. It lays out an action plan for solving the climate crises.

His biggest surprise, after working for almost two years at KKR, is the people. “They are nice people, and sometimes that’s a bit unexpected on Wall Street,” he quipped.

The following transcript has been lightly edited.

What has been the biggest change in your thinking and strategy since joining KKR?

The key question for me has been: How do you leverage the strength of KKR – that culture and the breadth of the platform and its past in private equity, in industrials, in infrastructure – to position it where it makes sense in climate? How can it be additive to the existing pools of capital?

If you look at private capital deployment in climate, you find two types of players: infrastructure funds that invest in renewables, and early-stage investors who are there to derisk climate technologies that we will need to really decarbonize the economy. There’s a missing middle that nobody is addressing. Once you have derisked your technology, you need a lot of capital. There is that kind of valley of death that climate companies have to cross, and this is what we are focusing on.

We are in a phase now where the green product cannot be more expensive because it’s green. The green premium is tolerable for a very short period of time. It’s the same with climate investing. Investors want to see returns and meaningful impacts on decarbonization. So we have put in place a strategy that is doing this – a growth infrastructure approach, but at the same time making sure that everything we do is true to the mission of decarbonization.

Every investor is looking for the next ‘solar’. Might this be found in this set of technologies that you are looking at?

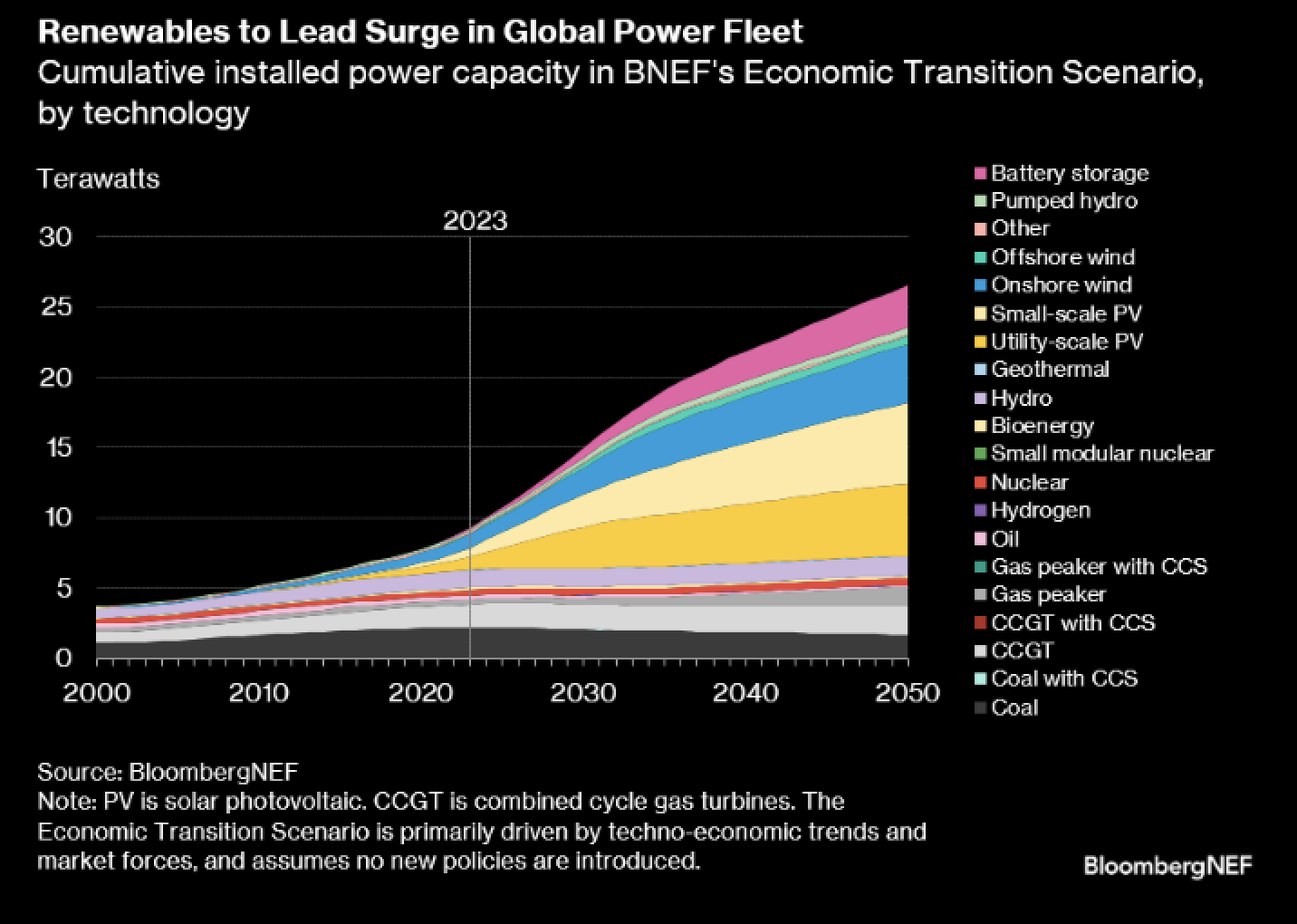

I would say that batteries are probably the next solar. They are being used for electrifying ground transportation – cars and buses and trucks – [and] to balance the grid in front of the meter and behind the meter. There is going to be a vehicle-to-building and a vehicle-to-grid story. Battery technologies are maturing extremely quickly, and the cost curve is going down quite rapidly. We are electrifying the entire economy – we’ll need three times more electricity by 2050 than what we use today because we are electrifying a lot of processes, and because AI is going to consume more electricity. It’s simply much easier to install a battery than to do a transmission line. We need both transmission lines and batteries, but batteries are going to probably grow faster because the cost of the technology is going to make it very affordable.

In EVs, I think the big opportunity is in commercial vehicles, like last-mile deliveries, buses, trucks. The economics are going to be very compelling.

The success of solar was partly attributable to concentration of manufacturing in one center – China. Does the whole focus on supply chain security, and some sort of onshoring push, hit the growth path of batteries?

I don’t think so. The supply chain for battery manufacturing is still being created. There are enough metals on the planet – copper, lithium, manganese, iron – to make batteries. There is no such thing as peak lithium or peak copper. We need to mine more of it, and sustainably. It’s true that today 90% plus of the refining capacity for batteries is in China and you have supply chains which, because it’s early still in the game, are not always very logical. If you extract lithium from somewhere in South America to make batteries in Europe, it goes to China to be refined and then back to Europe for the batteries. You cannot have those metals going around the world and having that carbon footprint.

The supply chains for metals, and the refining and preparation of the components, will change over time. The battery is 40% of the carbon footprint of the car, 40% of the weight of the car, 40% of the cost of the car. So if you’re an automaker making cars in the US or in Western Europe, beyond any geopolitical consideration, you want your batteries to be manufactured close to where you make your car so you don’t add to the carbon footprint and are able to lower costs. You will have more local manufacturing.

The adoption of EVs – passenger cars, trucks and buses – differs across regions. The opportunity is in building the infrastructure to charge these vehicles. One of the big applications that we will see in the US is the electrification of drayage in US ports, especially on the West Coast.

How do you see the opportunities geographically?

We think global. We want to go to sectors of the economy where there are a lot of emissions – energy, transportation, hard-to-abate sectors, so industry, buildings, data centers, food and agriculture, and to countries where you have a lot of emissions, so developed economies. We are focusing on high-emitting sectors and high-emitting countries. This is why most of what we do is 40% in North America, 40% in Western Europe and 20% in developed Asia, because that is where the emissions are.

There will be a new administration in the US in January. How does that that inform your strategy?

By definition, we are long-term investors with patient capital and we invest beyond political cycles. Initiatives like the IRA [Inflation Reduction Act] here in the US, the European Green Deal, or the Canada Growth Fund bring forward the investment decisions. They help derisk, so the business, thanks to those policies, is in the money and creating jobs probably two or three years before it would if you just left it to market forces. There’s a local component of job creation, wealth creation and value creation. All the governments, regardless if they lean left or right, have understood this in developed economies. As investors, we avoid taking regulatory risk. If you need to subsidize a business for 25 years, that is probably not the right technology or the right business. We cannot subsidize our way through the transition.

We are hearing about the investments and jobs in Republican-leaning states due to the IRA. Many of these states also have anti-ESG legislation and are trying to rollback EV mandates. Is there an anti-decarbonization counterwave that we are missing?

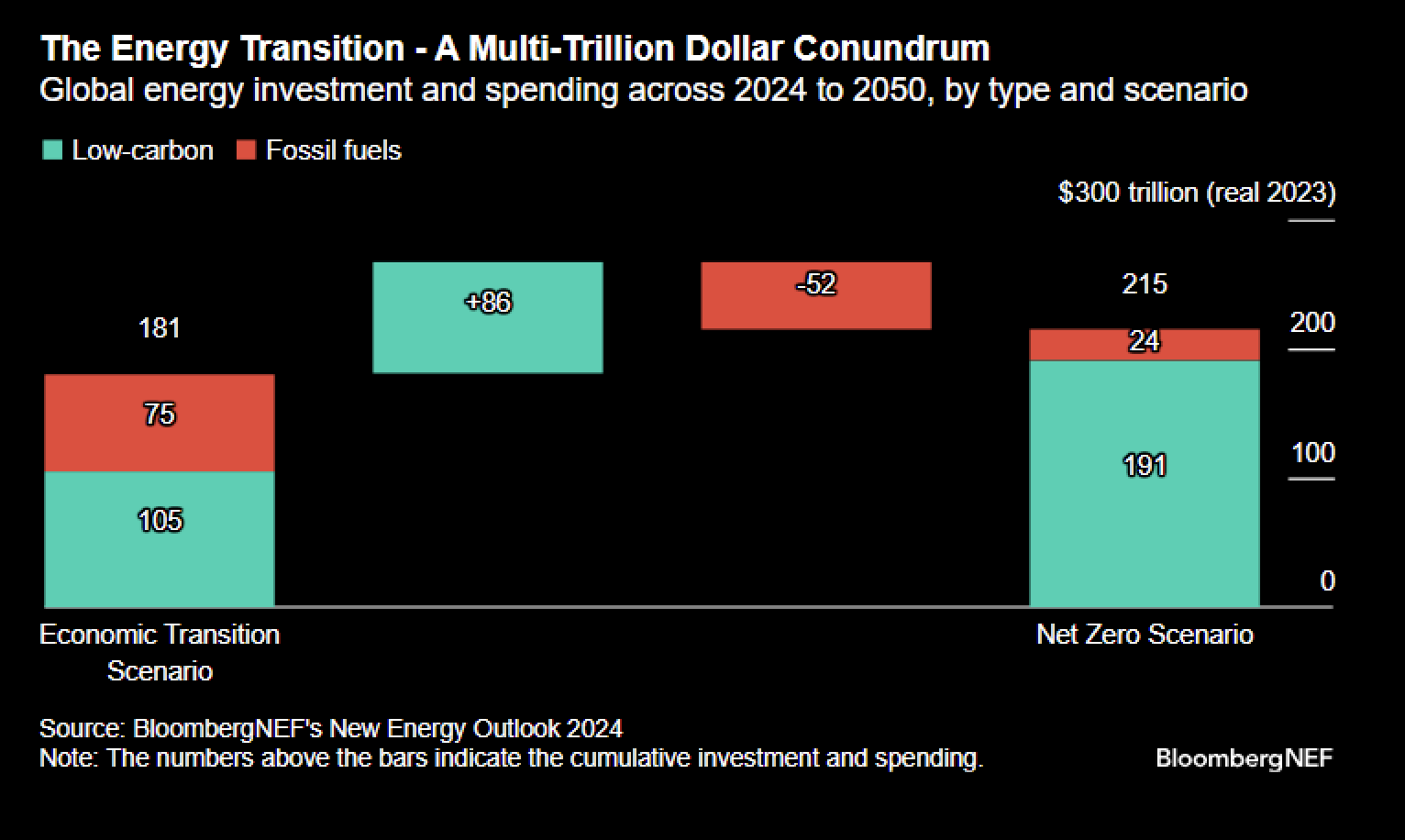

This is a multi-decade transition. We have to get to net-zero emissions. It’s going to take 30-40 years and some $180 trillion, according to BNEF. We are all together adjusting the system. In the last decade, you had a lot of ESG mandates and top-down policies: let’s ban combustion engine cars and limit their sales. This created some backlash. Post-Covid, we have policies like the IRA which are a bit more balanced, because they offer carrots and sticks. We have incentives to create new supply chains. Changes in energy and transportation and infrastructure take time. A just transition is a transition where, during the interim period, energy remains affordable and available.

There is an inflationary impact of some new technologies – because you have a green premium at the beginning. If we are too radical in the transition, we have a risk of creating too much inflation in the system. It would create a huge backlash and stall the entire system. So it’s okay to keep a little bit of fossil fuels for a period so that we guarantee that the energy system is always safe, available, affordable and we don’t create too much inflation. I think that’s the price to pay. New technologies – because you have innovation – eventually become deflationary. See solar today. It is the cheapest way to create electricity. We will reach the same point with batteries, and other decarbonization technologies.

Are you saying that net-zero emissions by 2050 is unlikely?

No. I am optimistic. I think 2050 is reachable. You need 12-15 technologies to decarbonize the economy. Solar is in the money. Wind is in the money. Batteries are getting there. EVs are still growing. There are reasons to be optimistic.

To reach net-zero by 2050, we need to start paring down investments in oil and gas. The opposite is happening. We are consuming more coal, oil and gas. How can rising fossil fuel investments sit with net-zero ambition?

That’s assuming that those fossil fuel investments in exploration are going to have a very long life. Take the example of biomethane, which involves capturing gas from biogas from landfills or dairy farms. Today, the biomethane market is extremely dependent on subsidies. Over time, as this industry grows, biomethane becomes profitable. That will make the hurdle for new gas exploration extremely difficult. If you’re investing in gas exploration today, you don’t consider biogas as competition. That may change tomorrow. We will also see a consolidation of oil and gas companies. It has already started. There are also markets where it’s difficult to imagine that you can completely decarbonize – like shipping and long-haul flights. That is why some carbon capture is needed to offset a part of these.

What is the size of the climate investments in KKR’s overall portfolio?

Over the last 15 years, KKR has invested over $34 billion in climate and environmental sustainability solutions. A lot of it has gone to renewables, circular economy, waste-to-energy systems, energy efficiency for data centers and cooling systems for data centers. Now we are doubling down with our climate strategy. We’ve done three investments so far: Zenobe [KKR announced an investment of $750 million last year] in the UK is about grid storage. There is a very high penetration of renewables especially wind in the UK, so you need a lot of batteries to solve for intermittency. It is also about commercial vehicles – electrification of the bus systems in many British cities, especially London. Second investment is a company called Avantus [investment not disclosed], which offers very high quality solar and storage project development in California and Arizona. The third is in Spain, with a company called Ignis to launch Ignis P2X. As part of the joint venture agreement, KKR will provide up to €400 million to develop and build future projects. It’s a hydrogen developer where we are targeting hydrogen offtakes for fertilizers, refining, methanol and green steel – all sectors of industry that cannot really be electrified by 2050, and where you will need a bit of green hydrogen. On average, we’re talking about deployment of between $400 million and $700 million of equity capital on every deal, with a holding period of 5 to 7 years. That should be enough to stabilize those assets and make them attractive to traditional infrastructure funds. Just like solar and wind are today the bread-and-butter of many infrastructure funds, tomorrow it will be batteries. This is a unique approach we are taking – we are thinking like infrastructure investors on those assets.

Skeptics would say that investors only care about returns, with climate being a secondary consideration, if at all. How would you respond?

I would obviously pushback on this. Before joining KKR, I was at Schneider Electric. I spent 27 years there with the last 10 as part of the executive committee designing the transformation of Schneider into one of the most sustainable corporations in the world. I thought hard about where action is needed to really decarbonize the economy. Private capital is required, but you have to offer returns. It’s not decarbonization or returns. Both are needed.

Every investment from our strategy has to follow three tests: relevance, significance and credibility. To be relevant, the investment has to be in a high-emissions segment, so energy, transportation, hard-to-abate sectors like buildings, food and ag. Significance test for the emissions reduction in a supply chain: whose Scope 3 emissions are we solving for? The third test is about the ability to measure and track the volume of emissions removed from the economy. No investment can go through the finish line if it doesn’t comply with the three. It’s all third-party audited by specialist firms because we have to guarantee that that we’re really decarbonizing.

In terms of overall KKR investments, across our majority-owned private equity and real assets companies, over 90% of financed emissions are directly measured and over 80% of financed emissions are addressed by business-relevant decarbonization plans. We work with our portfolio companies to help them develop sustainability strategies.

How big is KKR’s climate team?

We are roughly full-time equivalent of 20 people and leverage the breadth and strength of the KKR platform. Consistent with KKR’s collaborative approach, we pull from all areas of the firm to support our climate strategy, including our sustainability team, Capstone, and others.

Which is the one policy intervention you think could really accelerate the speed of decarbonization?

Grid. Especially in this part of the world, and in Europe also. The consumption of electricity is going to triple by 2050. We are going to solve part of that problem with batteries, a lot of distributed generation and vehicle-to-grid and other small things. But the way we manage the grid, the way we regulate utilities – that has to change. We have been incentivizing CEOs of utilities in a certain manner, we have been regulating utilities in a certain manner. Now we need a smarter grid and a more decentralized grid, and a different way of management.

What needs to change in how we build, manage and regulate grids?

Most grid operators and regulators are incentivized to add more capex to the grid, especially in generation, transmission and distribution, that is to make a bigger grid, when they face an increase in power demand. That works well when power demand rises more or less in correlation with the GDP of a region or a country. But when phenomenon like the decentralization of generation and storage, the electrification of transportation and industry or the rise in electricity needs for data centers happen, that system doesn’t work anymore. We need to re-think how we generate, store, exchange and share electricity. The required technologies are available, it is mostly about how we structure and regulate the system. That transition to a new role of electric utilities and a new way to balance supply and demand is already happening in some regions. The best example is probably the UK right now, where it is not rare to see batteries, EV chargers and thermostats providing flexibility to the grid, instead of coal-fired or gas-fired power plants.

KKR’s Global Climate Strategy seeks to deploy existing climate solutions, scale new climate solutions, and support the energy transition. Details in its latest Sustainability Report.