The stakes have never been higher when it comes to combating climate change. But a post-pandemic resurgence in coal use shows how the world’s dirtiest fossil fuel won’t be an easy habit to kick.

“Humanity is on thin ice – and that ice is melting fast,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres earlier this week as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change revealed the final installment of its sixth assessment report.

Some rolled their eyes at such language, viewing his warning of a ticking “climate time bomb” as at best unhelpful doomsaying and at worst mere hyperbole. But if you actually sit down and read the 36-page summary released on the latest climate science, it’s hard not to come away thinking of the situation as anything other than dire.

Global warming has already hit around 1.1C above pre-industrial levels. Without an immediate and dramatic intervention, the all-important 1.5C limit could be breached as soon as the early 2030s, with each incremental overshoot of this threshold bringing more severe consequences – from more intense flooding and heat waves to expanded biodiversity loss and food insecurity.

This decade will be crucial in determining whether climate catastrophe can be averted. The IPCC concludes that warming can still be kept to 1.5C if emissions are almost cut in half from 2019 levels by 2030. But that will depend on the world ending its addiction to fossil fuels, especially the most polluting of them all: coal.

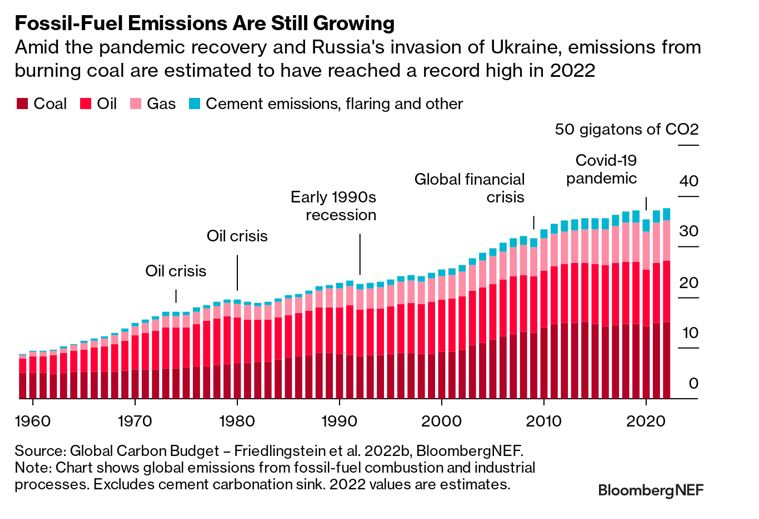

The path up to this point doesn’t bode well. As with other global crises over the past 50 years, the Covid-19 pandemic has proven to be a temporary reprieve for emissions, with reality falling short of hopes of a green recovery. Emissions from burning fossil fuels have resumed their upward march. The latest Global Carbon Budget from the Global Carbon Project estimates fossil-fuel emissions reached a record high last year and coal accounted for 40% of the total.

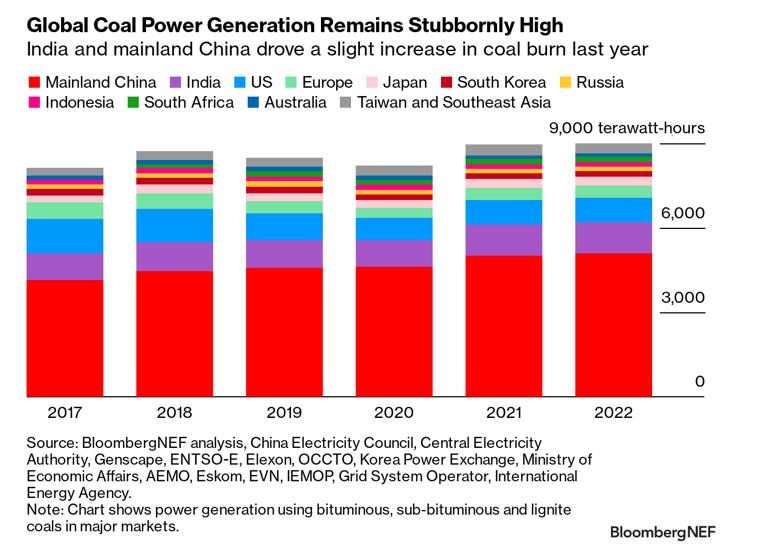

The endurance of coal emissions reflects the world’s bounce back from Covid-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sending gas prices spiking and countries scrambling to shore up their energy security. Even as China was mired in stringent lockdowns, it still sourced more electricity from coal in 2022 than before the pandemic. Together with growth in India and crisis-stricken Europe, global coal-fired power generation ticked up by 0.6% last year – a small increase, yes, but nonetheless indicative of how the world is struggling to tame its appetite for coal.

In the absence of abatement technologies like carbon capture and storage, the IPCC’s new synthesis report says that the projected emissions from existing fossil-fuel infrastructure will exceed the remaining “carbon budget” to limit global warming to 1.5C – in other words, the amount of carbon dioxide that can still be emitted.

To get back on track, Guterres has proposed an “Acceleration Agenda” that includes no new coal plants, and the phasing out of coal by 2030 in OECD countries and by 2040 everywhere else.

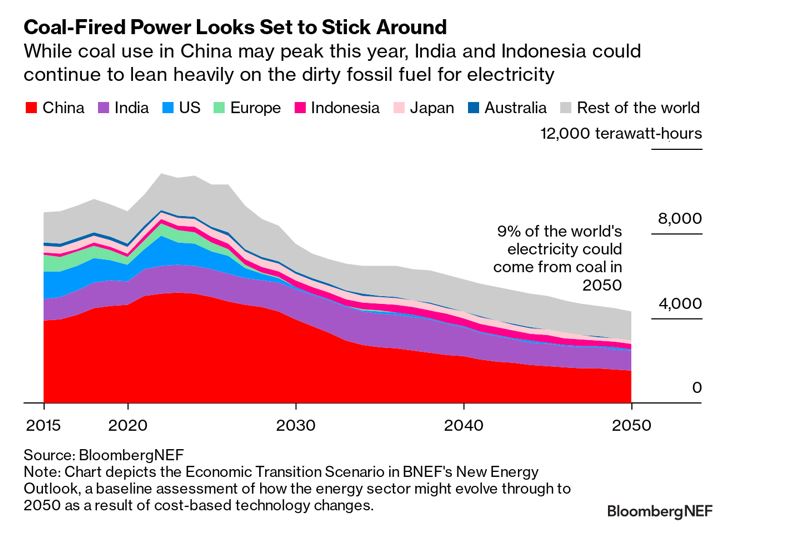

But while coal will likely see a long-term decline, new power stations are set to be built over the coming decades, with India and Indonesia, in particular, on course to grow their fleets. Coal-fired power could therefore remain a not insignificant force in 2050, according to BloombergNEF’s Economic Transition Scenario, which is based on the economic competitiveness of key technologies and assumes no new policies are introduced. Though generation from coal may have peaked in 2022 as renewables increasingly take over, it could still meet 9% of the world’s electricity needs by mid-century, from around 36% today.

In this scenario, China remains the largest market for coal power, although its generation drops by 71% between the pinnacle reached in 2023 and 2050. India, meanwhile, sees it hunger for coal continue to expand well into the 2030s before easing.

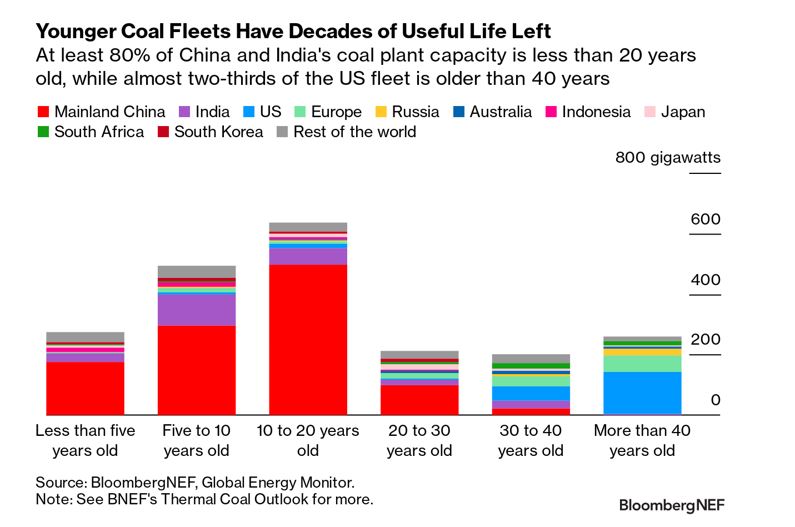

As developing economies look to strike a balance between economic growth and climate concerns, their coal use could rise to satisfy higher power demand. This reflects cheap domestic coal, such as in parts of Asia, but also relatively young coal plants.

China is home to the world’s largest coal power fleet and almost 90% of its capacity is less than 20 years old. It’s the same situation for 80% of India’s fleet, meaning these relatively young assets could conceivably keep running for decades before being retired.

This contrast the likes of the US and Europe where the vast majority of coal power stations are older than 30 years. These aging and less efficient plants are more expensive to run and maintain, and often less suited to ramping up and down to compensate for the intermittency of renewables. Facing the rapid buildout of wind and solar farms and strengthening carbon price signals, coal plants in these regions are ripe for early retirement. BNEF’s Economic Transition Scenario sees minimal generation from coal assets in these markets in 2050.

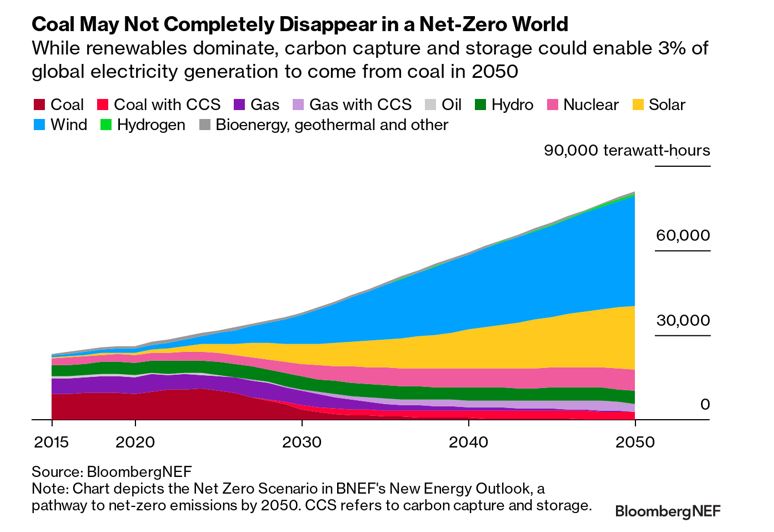

Yet, coal could still be around in a world that manages to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. BNEF’s Net Zero Scenario, which is consistent with 1.77C of global warming but still has a 33% chance of sticking to 1.5C, envisages 3% of global electricity generation coming from coal by mid-century. However, unabated coal virtually disappears as carbon capture and storage is increasingly deployed from the end of this decade. China, India and Indonesia are seen as the the main markets still leaning on coal in a net-zero world amid relatively lower prices versus gas.

Ensuring the near or total demise of coal won’t happen by inertia. Further policy is required to accelerate the transition and financing needs to be shifted from fossil fuels to clean energy.

Public and private funding for low-carbon energy supply has yet to outweigh the capital being poured into coal, oil and gas. While annual investment in the energy transition and electricity grids topped $1.3 trillion last year, BNEF estimates this will need to scale up to $7.9 trillion by the 2040s to reach net-zero emissions.

“The choices and actions implemented in this decade will have impacts now and for thousands of years” was one of the more sobering lines in the IPCC’s report. But it’s also a sign of hope. There’s still time – albeit rapidly dwindling – to make sure the world doesn’t blindly stroll past the point of no return.