By Willa Tobin, Weather Analyst, BloombergNEF

Anthropogenic emissions – or emissions caused by human activities – are shifting weather patterns worldwide. And this meteorological disruption is trickling down to commodities.

Daily weather impacts heating and cooling needs. Extreme weather events can disrupt infrastructure and cause power demand spikes. In sum, changing weather can throw commodities markets off balance, snarl supply chains and distort the prices of energy commodities.

Five of the impacts of these shifting weather patterns are already playing out in energy and commodity markets today.

1. Winters are getting warmer, leading to wimpy gas withdrawals

. Winter temperatures across the US have risen 2% in the past 10 years, compared with 1990-1999 levels. This decreases total residential and commercial heating demand, leading to higher natural gas storage levels and lower natural gas prices. A one-degree Fahrenheit shift in average winter temperatures can cut annual gas withdrawals by 6% on average. As winters grow milder, the need for larger gas inventories decreases, causing utilities to redefine storage volumes and pushing gas producers to turn to exports as a source of revenue.

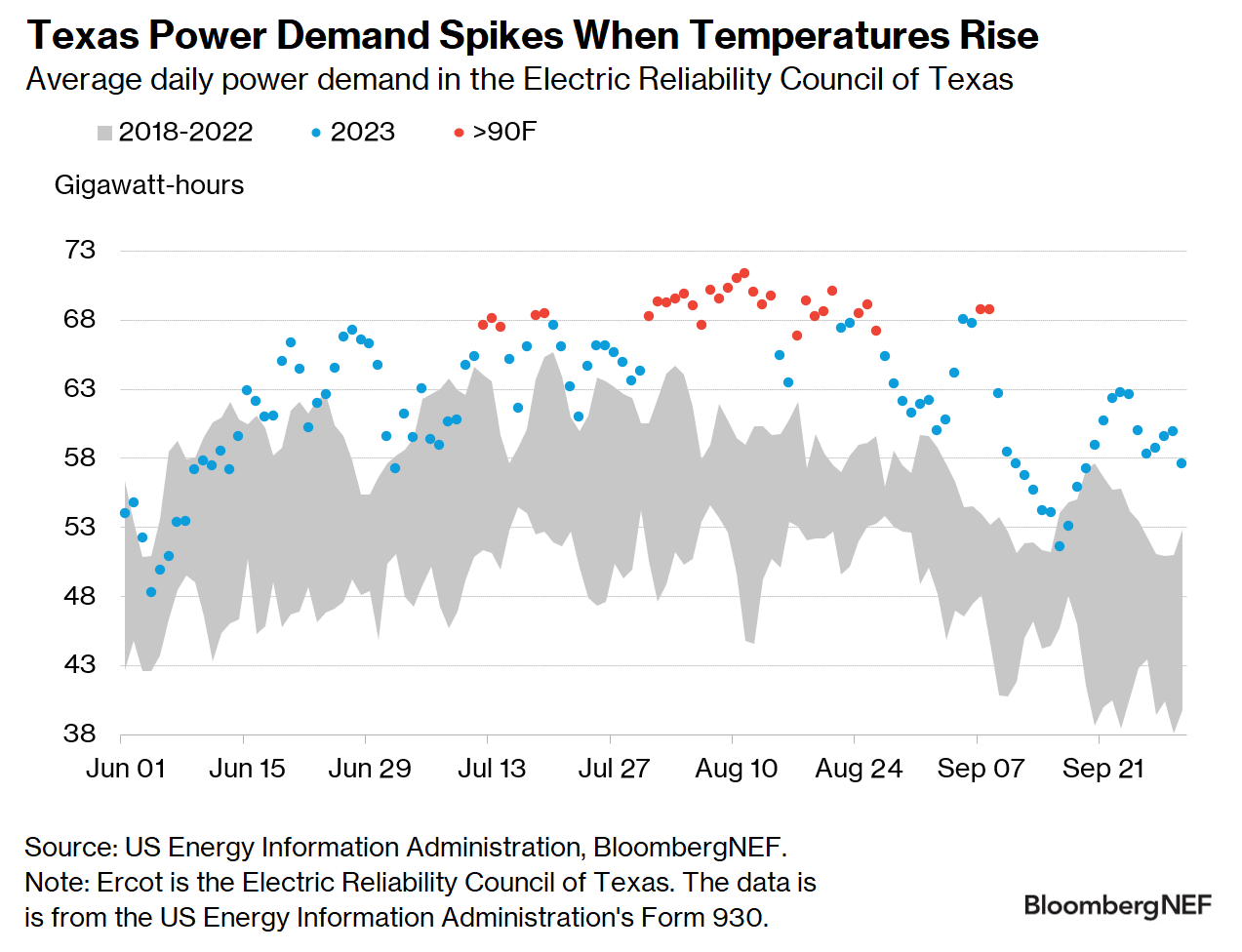

2. US summers are already hot – and they’re stressing power grids as they get even hotter.

Annual cooling degree days – a measure of how much above “comfortable”, or 65 degrees Fahrenheit, a day is – have increased 17% compared with the 1990-1999 average, and the summer of 2024 was the hottest ever recorded. Summer heat is dangerous for power grids: as people crank up their air conditioners, power demand soars, stressing the grid and raising the risk of blackouts. Fossil fuels are then called into action to supplement generation from intermittent renewables, causing the energy transition to make a U-turn.

3. The northwest is getting dryer, making hydropower wither

. Summer precipitation for the northwest has decreased by 26%, comparing the average from the past 10 years (2014-2023) to the 1990s (1990-1999). That’s obviously a problem for agriculture. It’s also a problem for the region’s energy supply, which is dominated by hydroelectric projects. When rain is scanty, hydro reservoirs rely on melting snow to maintain robust water levels. But the fraction of winter precipitation that is falling as snow in the region is steadily declining, dropping at an average rate of 0.6% per year since 2000. If this trend continues, the region could see a decrease in conventional hydroelectric power generation, impacting the business models of utilities and independent power producers.

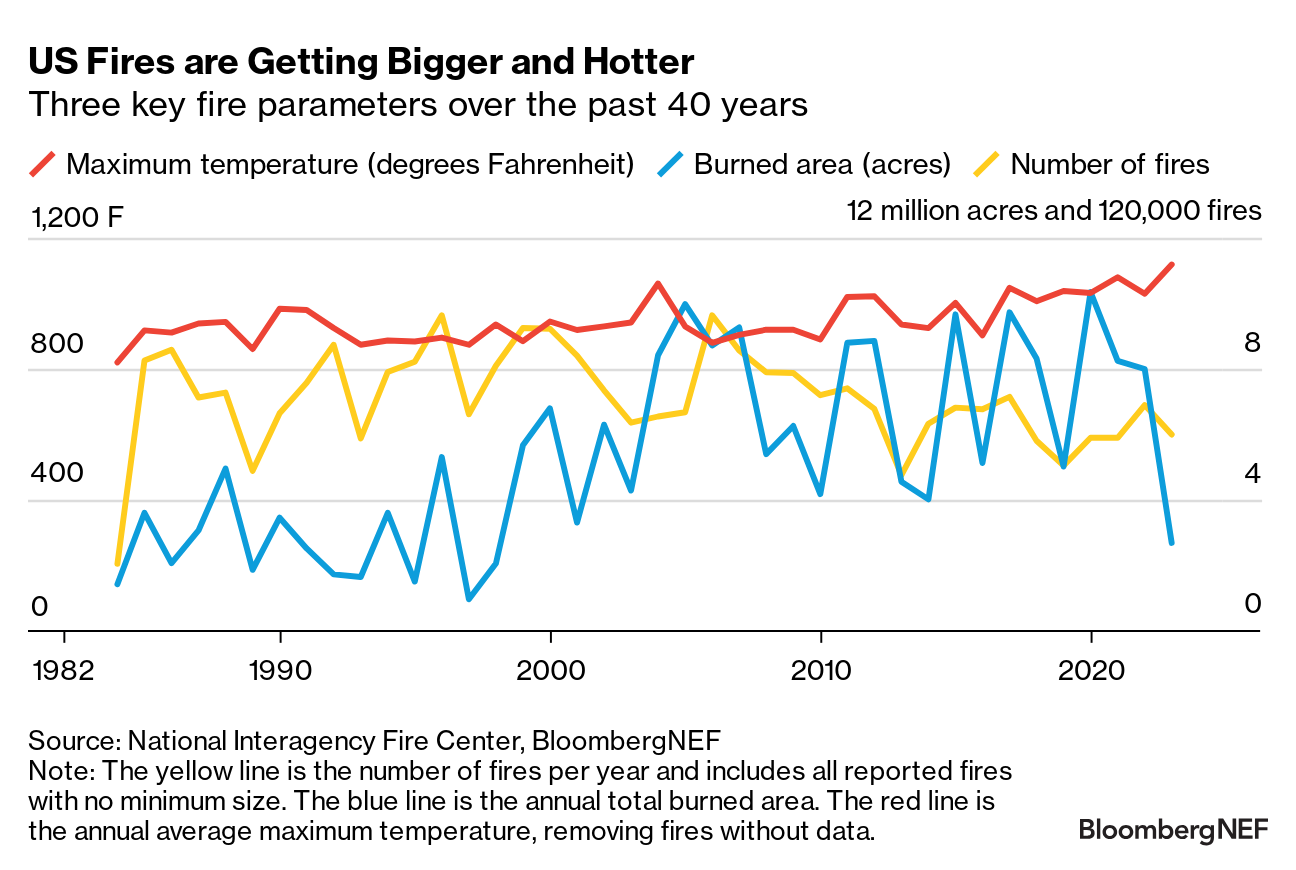

4. Wildfires are expanding, menacing homes and infrastructure

. The annual burned area from US wildfires has more than doubled compared with the 1990-1999 average, as fire-conducive weather conditions become more frequent, and fires get bigger and hotter. The western US has seen a particularly large spike in wildfire-related damages, with the Southwest adding an additional month of annual fire weather days over the past 50 years. Fire temperatures are also rising, increasing at a rate of 3.7 degrees Fahrenheit per year since 1984. That is making fires more dangerous for people and infrastructure. Utilities with power lines in fire-prone regions will need to take these risks into account as they build out their grids and make plans to boost resilience.

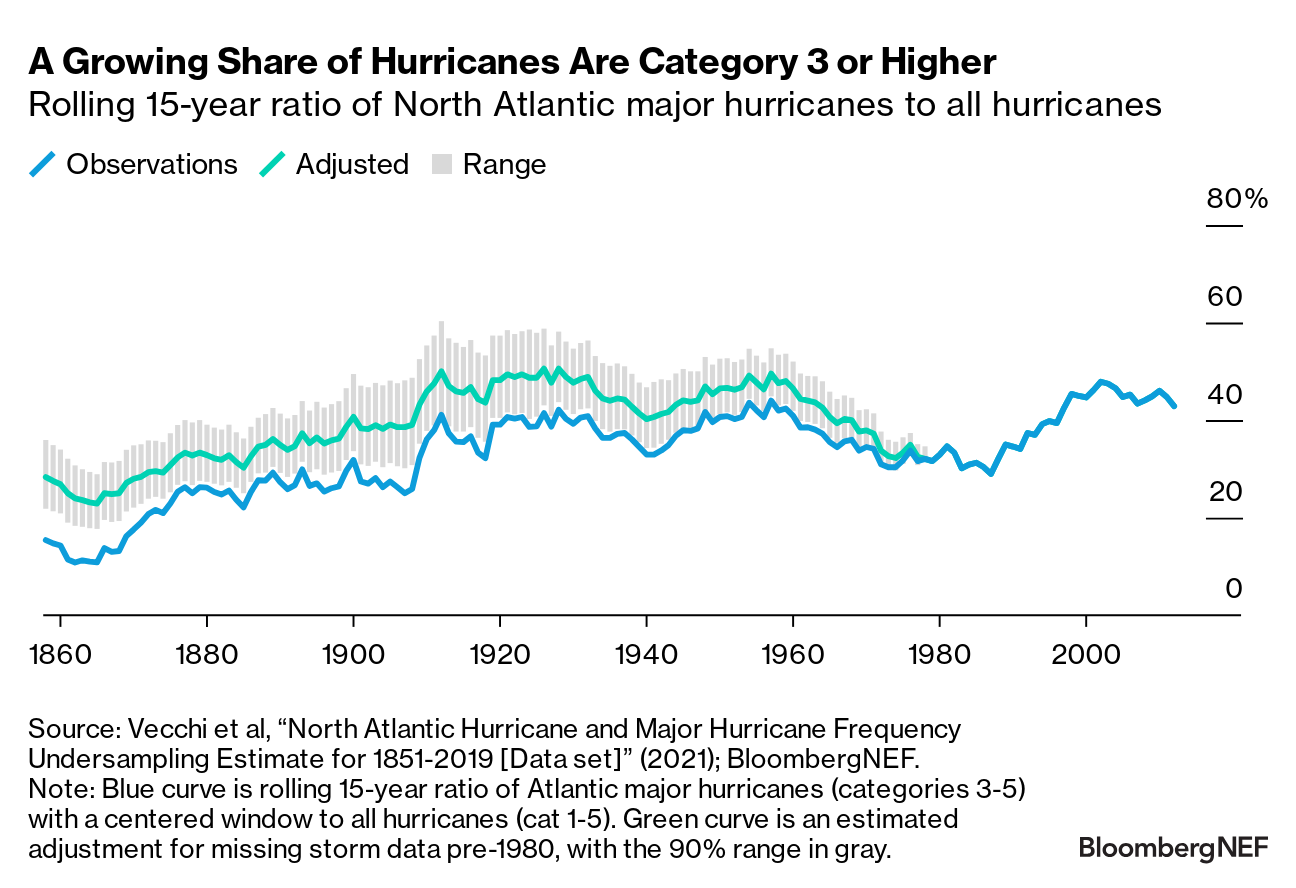

5. Hurricane conditions are worsening, walloping oil and gas infrastructure

. North Atlantic hurricanes are the costliest extreme weather events for the US, racking up more than $1.3 trillion in damages since 1980. Hurricanes also pose tremendous risk to offshore oil and gas production in the Gulf of Mexico. Most major production declines in the region correspond with major hurricane events since 1990. Today, more storms in the North Atlantic basin are reaching major hurricane strength and scientists expect the hurricane intensity to increase with global warming.

With these weather patterns expected to persist – and even intensify – in the coming years, stakeholders ranging from financial institutions to policymakers and energy companies will need to begin accounting for the above risks in their long-term strategic planning.