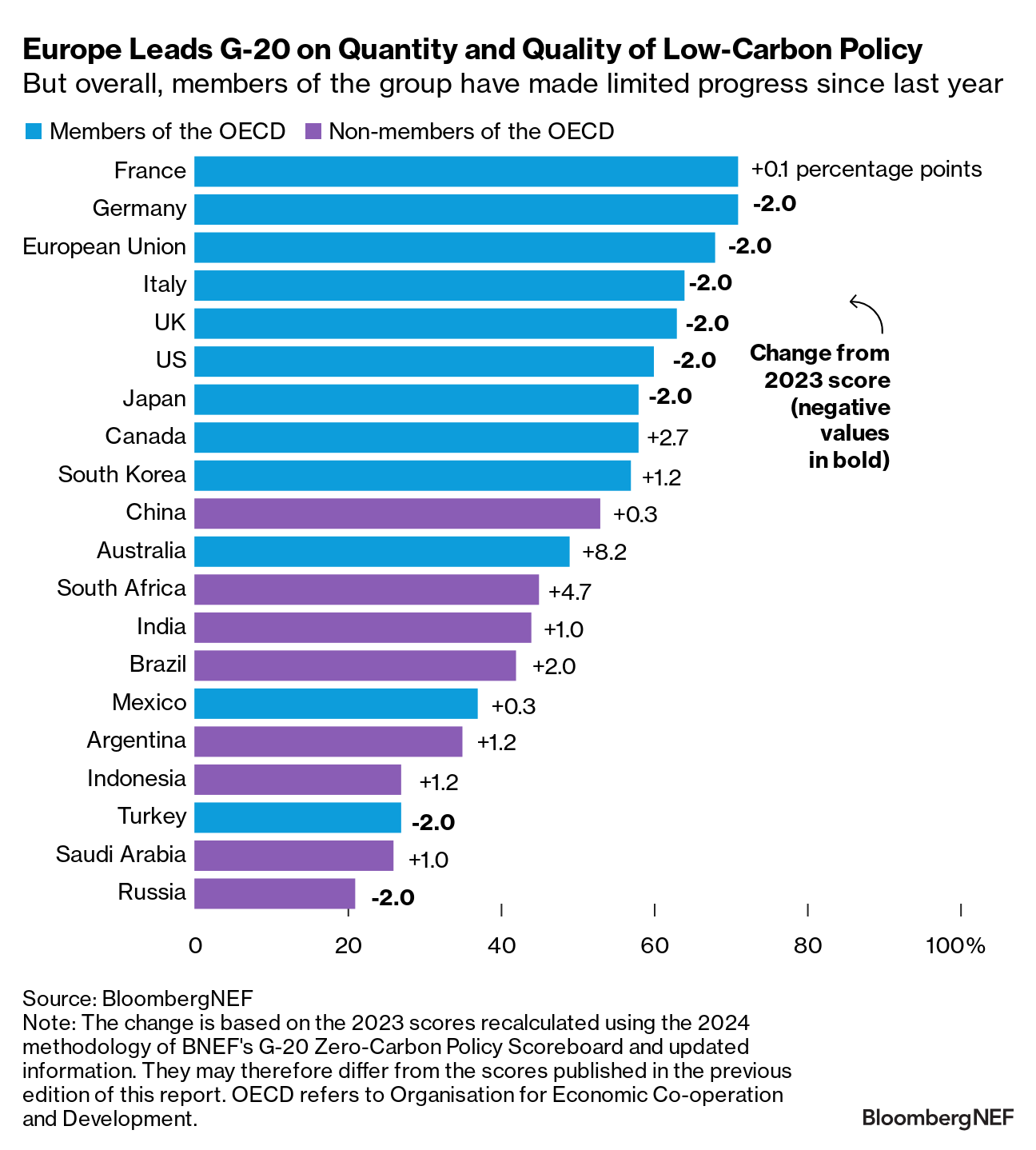

The world’s largest economies have made limited progress in boosting their decarbonization policies over the past year – a red flag for climate action as the urgency of the crisis ramps up.

In the fourth annual edition of BloombergNEF’s G-20 Zero-Carbon Policy Scoreboard, the members of this group scored, on average, just 49% – a paltry 1 percentage point rise from 2023.

The European Union, UK and US retained the top spots. But these high scorers failed to improve their performance from last year, in fact seeing an average decline of 1 percentage point. As developed economies responsible for 18% of global greenhouse gas emissions, they should lead by example, in particular to encourage emerging markets to follow suit.

Top scorers lost points for policy delays, abrupt changes and weakened regulations

The EU and UK held on to the top five places in BNEF’s latest ranking thanks to their provision of incentives for low-carbon solutions and increasingly stringent regulations to disincentivize emission-intensive technologies.

However, these leaders, as well as the US, saw their total score decrease. In some cases, they scrapped low-carbon programs like Germany’s purchase subsidies for electric vehicles, slowed progress on the ground such as renewables build, or faced other challenges including political and industry opposition, and red tape.

They especially lost points for increasing uncertainty among consumers, industry and investors. This was due to insufficient or delayed information on new policies, ending programs earlier than expected, and weakening low-carbon regulations or deadlines.

Developed economies should lead by example, but large emerging markets need to up their game

The dividing line of economic wealth persists. In general, developed economies have more and better low-carbon support than emerging markets. Members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development scored, on average, a total of 57% in BNEF’s latest assessment, compared with 37% for non-OECD economies.

To limit global warming to 1.5C, it will be especially important for developed economies to take the lead by implementing increasingly ambitious regulations and mandates on emissions-intensive technologies and practices. But it will be equally important for large emerging markets to make progress, and developed countries can support policymakers there. Accounting for 43% of the world’s emissions, the ‘BRICS’ – Brazil, Russia, India, mainland China and South Africa – have an average policy score of 42%.

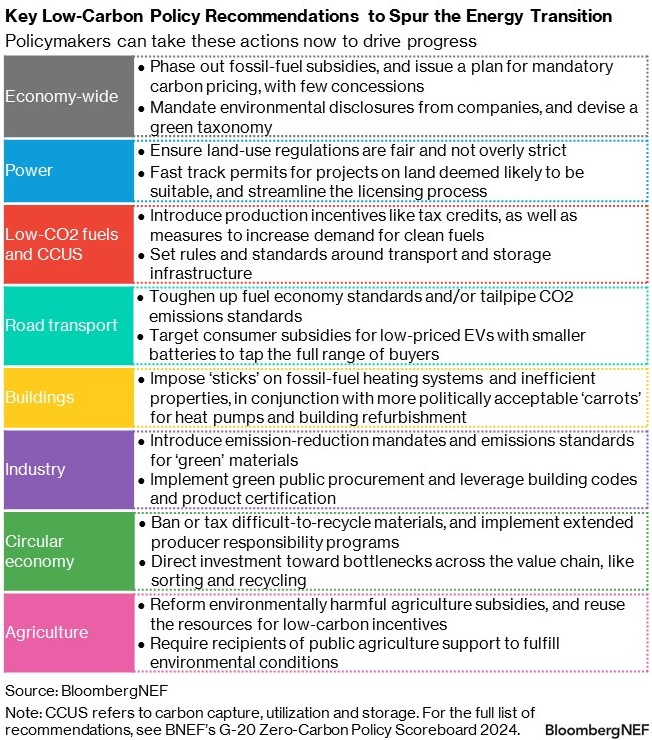

Policymakers can take action in the near term to kickstart momentum

All G-20 markets need more support in ‘harder-to-abate’ sectors where cleaner options are limited or very costly, especially industry, buildings and agriculture. Their policy regimes averaged 57% for clean power support and 51% for road transport – where economic low-carbon solutions are more readily available – compared with 41% for the other sectors evaluated in BNEF’s Scoreboard. These hard-to-abate areas need a mix of incentives and regulations, especially to build up demand and ensure any required infrastructure is built.

There are concrete actions that policymakers can take in the short to medium term. With overall momentum having stalled, governments across the G-20 need to rapidly introduce more and better low-carbon policy support if the world is to reach net zero by mid-century and achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.

The BNEF Policy Scoreboard scored each G-20 member out of 100% based on the volume of government support implemented to cut greenhouse gas emissions, the robustness of these programs and the policy-making process, and metrics to gauge whether they are starting to drive change on the ground.

A comprehensive executive summary of the report can be found here.