By Kamala Schelling, Editor, BloombergNEF

Hydrogen may be a small molecule, but it’s hugely important when it comes to decarbonizing industry. Already widely in use as a chemical feedstock and fuel, hydrogen, or H2, is also central to net-zero strategies – but only if it can be produced without generating carbon emissions.

“The problem is that clean ‘green’ hydrogen has always been far more expensive than its dirty ‘gray’ counterpart,” says Adithya Bhashyam, a hydrogen analyst at BloombergNEF.

That’s about to change.

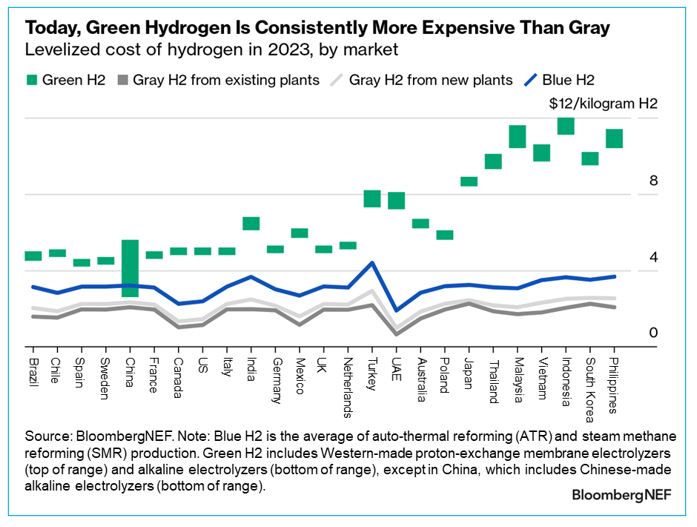

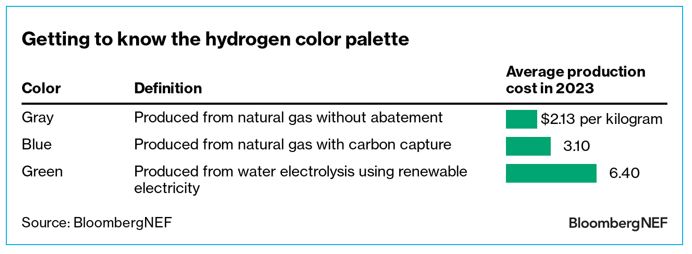

“When it comes to producing green hydrogen today, the numbers are stacked against us,” says Bhashyam. “Gray hydrogen, which comes from natural gas, costs $0.98-$2.93 per kilogram to produce. Blue hydrogen, or hydrogen produced with fossil fuels but subject to carbon capture, costs $1.8-$4.7 per kilogram. And green hydrogen, which is produced by running an electric charge through water, costs a whopping $4.5-$12 per kilo. In every single market we’ve surveyed, green hydrogen is more expensive than its gray counterpart.”

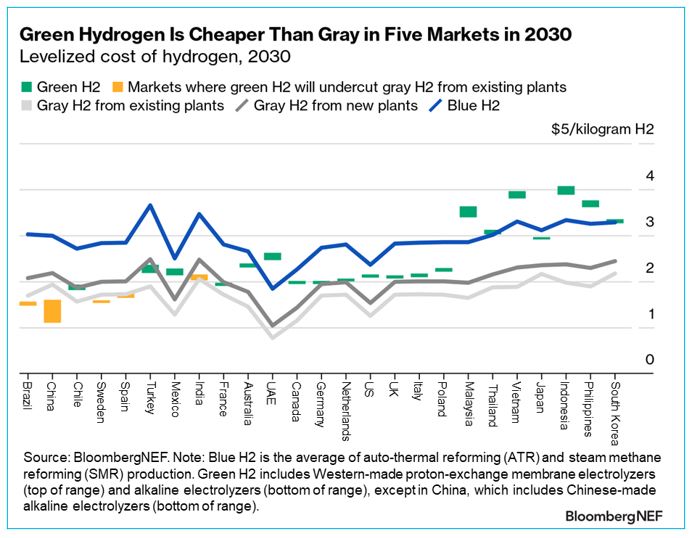

Yet in their most recent levelized cost of hydrogen analysis, Bhashyam and his team found that a tipping point is just around the corner. From 2030 on, they find, producing green hydrogen in a new plant could be as much as 18% cheaper than continuing to run an existing gray hydrogen plant in five major economies around the world.

“In Brazil, China, India, Spain and Sweden, green hydrogen from new plants is going to start undercutting gray hydrogen from existing plants by the end of the decade,” says Bhashyam. “Remarkably, this holds true even for green hydrogen plants built without subsidies.”

When compared to newly built gray hydrogen plants, the outlook for green hydrogen is even better: by 2030, a new green hydrogen plant outcompetes newly built gray hydrogen in eight of the 28 markets modeled in BNEF’s 2023 Hydrogen Levelized Cost Update. Nor is green hydrogen likely to be pipped by blue. “Using Western-made alkaline systems, green hydrogen beats out blue hydrogen by 2030 in all but a handful of modeled markets,” Bhashyam says.

The dramatic drop in the price of green hydrogen is due to two key factors: economies of scale, and supportive policy. “The more electrolyzers are deployed, the cheaper they’ll become,” says Bhashyam.

On the policy front, the US Inflation Reduction Act tax credit for clean hydrogen – which has no budget cap and thus can offer funding to as many projects as meet the emissions criteria – will likely have a huge impact on the country’s green hydrogen production.

The EU is also planning to establish a ‘Hydrogen Bank’ this year, a subsidy mechanism for commercial scale projects similar to the IRA but with a fixed budget.

“Green hydrogen isn’t the first clean technology to be cheaper than existing fossil fuels,” Bhashyam observes. “Solar and wind generation are already cheaper in many markets than fossil-fuel-based power. But for hydrogen, which has so long been the expensive one out when it comes to climate-friendly power generation, to be able to join that group – well, that’s pretty cool.”