By Bernardo Burga, Renewable Fuels, BloombergNEF

Maritime shipping, the lifeblood of the global economy, has long depended on dirty, carbon-intense heavy fuel oils – garnering it a reputation as notoriously hard-to-abate. Yet a push to decarbonize the sector is under way. Amazon, Ikea, Unilever, Michelin, DuPont and Target have all pledged to conduct shipping operations only with companies using carbon-neutral fuels. The International Maritime Organization and shipping companies themselves are establishing net-zero emissions targets. It’s now all hands on deck as the sector searches for a fuel that can help it clean up its act.

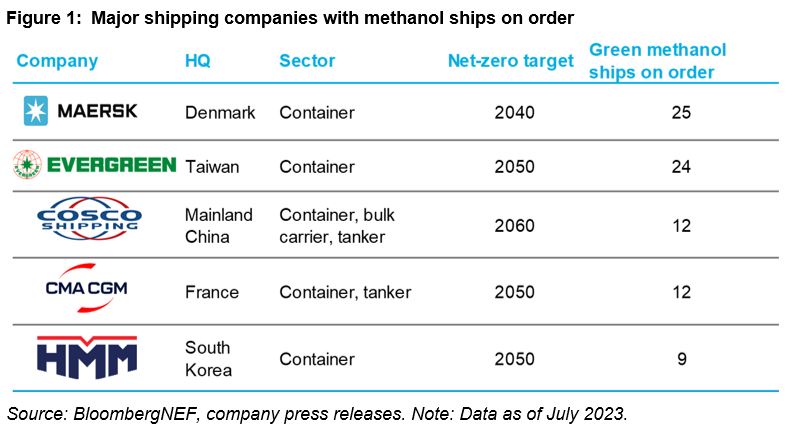

On this front, the biggest splash of the past year has come from green methanol, a fuel with little to no lifecycle emissions. Giant container lines such as A.P. Moller-Maersk and Evergreen are leading the charge by ordering more methanol-capable ships, indicating green methanol is their low-carbon fuel of choice.

What is green methanol?

Green methanol is split into two distinct classifications, bio-methanol and e-methanol, depending on the green feedstocks used. The former involves replacing existing coal or natural gas feedstocks with biomass or biogas, whereas the latter is synthesized by reacting green hydrogen with carbon dioxide from direct air carbon capture or biogenic sources. In either case, burning the fuel results in little to no lifecycle emissions, making it an optimal fuel choice for a net-zero scenario.

Methanol is also an attractive alternative to dirty fuels thanks to its chemical properties. Though it has a lower energy density than its fossil-fuel counterparts, methanol has chemical and combustion properties similar to heavy fuel oils, making its storage and handling much simpler than that of liquefied natural gas and ammonia. Methanol also boasts ‘drop-in’ capability, as modern dual-marine engines can burn and operate on both methanol and heavy fuel oils.

Policy could be the wind in green methanol’s sails

Nevertheless, shippers will still need an economic incentive to divest from fossil fuels. The European Union’s EU ETS and FuelEU policies – which will subject vessel emissions and carbon intensity to compliance fines – are a case in point.

These policies have two tiers of compliance: ships that travel entirely within the EU will be fined for 100% of their emissions, while those that travel to and from the region will be fined for only 50%.

Under the 100% scenario, green methanol ships will soon outcompete container ships and tankers powered by fossil fuels. Yet for vessels subject to fines for just 50% of their emissions, only container ships are projected to achieve a lower total cost of ownership by burning green methanol; tankers powered by green methanol are projected to remain significantly costlier than fossil-fuel-based ones.

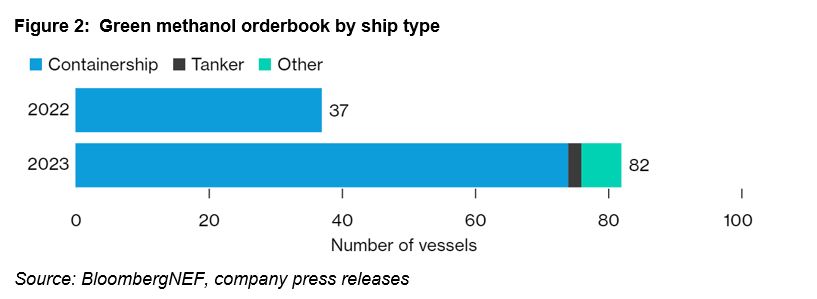

This discrepancy in cost competitiveness suggests that container ships could be where green methanol will find the greatest demand within the industry. The orderbook of methanol-capable vessels has more than doubled since 2022; the overwhelming majority of these vessels are container ships. In other words, major container lines are banking on green methanol as a key element for decarbonizing their operations, while tanker and bulk carrier companies remain bearish on a methanol rebuild.

Capacity needs to rev up – and fast

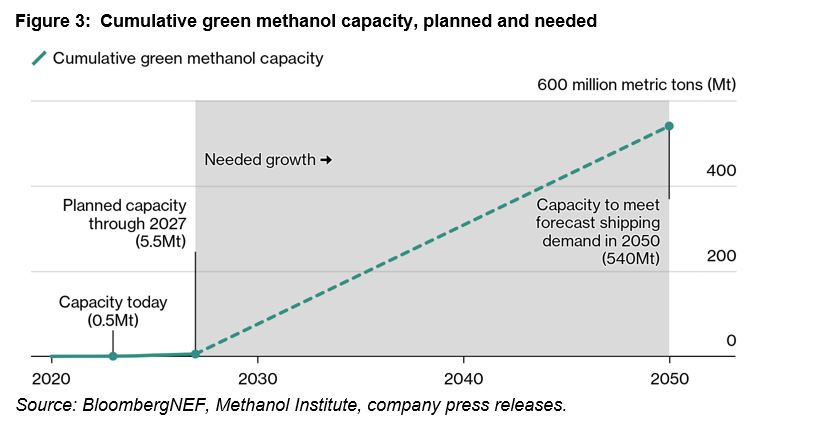

Though there is great optimism for green methanol within the shipping industry, there are still significant hurdles across the value chain for widespread methanol adoption. BNEF’s database of upcoming green methanol projects forecasts an annual capacity of 5.5 million metric tons by 2027 – roughly 11 times the capacity today.

This is an enormous increase, but it’s just a fraction of what is needed. Green methanol production would have to reach over 540 million metric tons per year to fully replace all marine fuel in 2050 – with feedstock cost and availability posing huge challenges to scaling production to such levels.

The distance between production and ports could leave green methanol in the doldrums

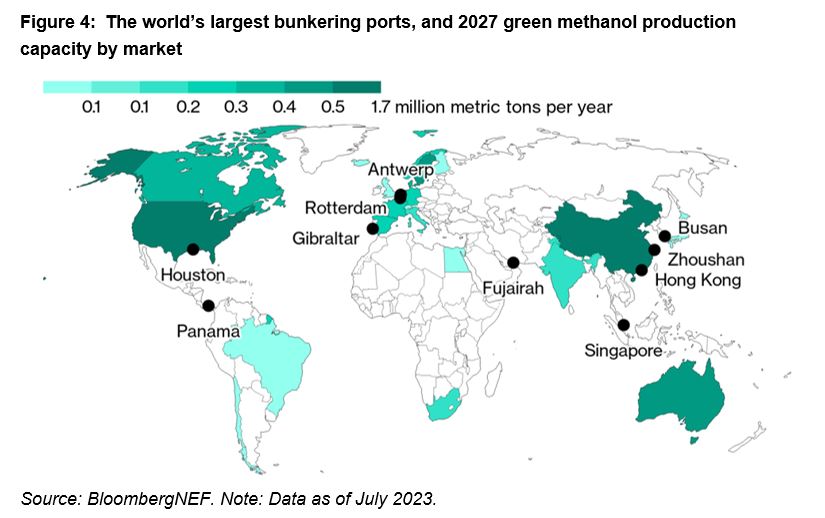

The distribution of green methanol’s production capacity in relation to the world’s major bunkering ports is another barrier to implementation. The world’s 12 largest bunkering hubs account for roughly 40% of worldwide ship bunkering, with Singapore alone accounting for 16% of all marine fuel sales in 2022.

The problem is that much of the world’s biggest green methanol producers are thousands of kilometers away. Transporting large quantities of green methanol to these traditional bunkering ports both threatens supply chains and pushes up bunkering costs, suggesting that a significant revamp in shipping infrastructure must occur before green methanol can be widely adopted.