By Albert Cheung

Head of Analysis

BloombergNEF

Clean energy has had a good pandemic. Global wind and solar deployments hit new records in 2020 and 2021, as did electric vehicle sales, and COP26 in Glasgow brought progress on several important fronts. Government net-zero targets now cover or are set to cover 90% of global emissions.

At the same time, the global energy and commodities crunch, the rapidly changing macroeconomic environment, and political challenges all cloud the horizon. It can be hard to discern which of these are real risks to the low-carbon transition, and which are probably red herrings.

High input and freight prices

For more than ten years the clean energy sector has been unremitting in driving costs down, such that equipment for renewables plants is as much as 10 times cheaper now. Many people working in renewables have known nothing but falling costs for their entire professional lives, and project developers often bake presumed cost reductions into project bids two, three and even five years ahead.

So the commodity price boom of the past months has been new ground for many. Higher prices for steel, copper, lithium, polysilicon, freight out of Asia and other inputs through 2021 have led to cost increases in an industry used to taking deflation for granted. The effects are rippling through the supply chain. Solar PV module prices were about 27 U.S. cents per Watt as of late 2021, up from 19 cents at the lowest point in 2020. The price of wind turbines in the second half of 2021 rose 9% to $930,000 per megawatt, according to BloombergNEF research.

BNEF’s levelized cost of electricity benchmark, or LCOE, for utility-scale tracking solar PV climbed 7% in the last six months of 2021. For onshore wind the gain was 4%. Lithium-ion battery prices did fall about 6% in 2021, but this is expected to reverse in 2022 as contracts closed in 2021 feed into the data.

These impacts are measurable and new. But a broader look at the energy sector casts them in a better light. BNEF’s LCOE benchmark for gas-fired power generation rose 12% in the second half of 2021, much more than for renewables, and Brent crude is 49% up since the start of 2021, at the time of writing. Through 2021, the cost of running existing gas- and coal-fired power plants in competitive markets has at least doubled. So even with higher costs, renewables are still competitive in markets that account for 91% of the world’s power generation.

There are also reasons to believe the higher costs for renewables will be transitory. The supply of polysilicon, which has been the biggest bottleneck for PV in recent months, should grow by 39% in 2022, according to BNEF’s solar analysts. This, for example, would relieve much of the sector’s pain and bring solar module prices back in line with the long-term trend. Freight, it is true, remains an unpredictable factor.

For batteries, the target is to get pack prices down to $100/kWh – the figure at which EVs are expected to start competing with conventional vehicles on an upfront purchase-cost basis, without subsidies. The long-term trend suggests this will be achieved around 2024. If we factor in continuing high input prices the date gets pushed back just two years to 2026.

So, while the short-term challenges are real and contract (re-)negotiations will be tricky for now, it seems like the clean energy sector needs to hold its nerve.

Rising financing costs

Alongside technology-driven cost deflation, expansionary monetary policy has been another important tailwind for the clean energy sector. BNEF has wondered for some years what to expect in renewables investment if and when interest rates corrected upwards, and we will probably find out in 2022-23 as central banks look to rein in inflation. Higher financing costs will surely lift the LCOEs of renewable power, and more so than for competing technologies such as gas, which are less weighted towards capex.

We have already seen this in Brazil, where the central bank raised its key benchmark rate to 7.75% last October. After factoring in higher equipment costs, which led to a 3% increase in project capex, onshore wind LCOEs have risen by 13-27% overall.

We have previously estimated that the LCOE sensitivities of onshore wind and utility-scale PV are around +$1-1.5 per megawatt-hour and +$2/MWh, respectively, for a single percentage point increase in costs of capital. This is equivalent to around 2.5% and 5% of the respective global cost benchmarks today.

Expect to see these changing costs reflected in project bids over time – but again, there are mitigating factors. The rise of sustainable debt, booming appetite for net zero-aligned investment opportunities and a rush towards ESG-focused assets means that there is more capital than ever available for clean energy and climate-related technologies, at least in developed markets.

The energy crunch and ‘greenflation’ concerns

As the energy crunch wears on, higher prices will increasingly feed through to consumers, leading to more soul-searching over whether ‘green’ policies are the cause of the pain. Some of this will come from well-meaning officials and commentators, but it will be amplified by those wanting to slow the low-carbon transition.

There are two notional mechanisms: either green policies are explicitly adding to the costs of energy via surcharges and carbon prices, and/or they are constraining investment into fossil energy supplies. Either way, they would be seen as stoking energy poverty and out-of-control inflation.

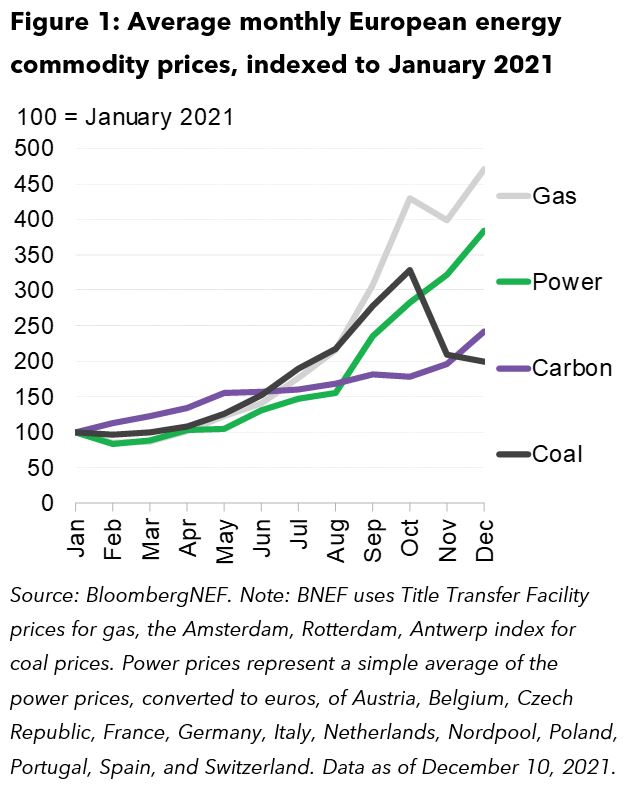

Both mechanisms exist in principle – and should be carefully considered for future policymaking – but neither plays anything more than a bit part in today’s reality. Green surcharges, including carbon prices, remain a small (and relatively stable) slice of the end user’s energy bill, while wholesale energy costs – the largest component – have ballooned. In the first five months of 2021, a 50% increase in EU carbon prices barely registered any impact on power prices, as shown in the European commodity price chart below. But in the second half of the year, as gas prices reached for the sky, power prices hitched a ride to roughly four times their starting point. As these increases feed through to consumer tariffs, they will bring economic pain – but those looking for a green policy bogeyman here will have to look elsewhere.

Indeed, power-price sensitivity to carbon prices will fall over the coming decade as the use of gas and coal decline, according to BNEF analysis. This is not to deny that there is a valuable discussion to be had about the investment costs of the energy transition, and whether the energy bill is the right place to put them.

As to the second charge, that green policies are constraining supplies of needed oil and gas: there is equally little evidence of this. What has happened over the last two years is that the former ‘swing’ producers in the U.S. oil patch have discovered a new sense of capital discipline. As BNEF’s Tai Liu has written, U.S. oil & gas producers are waiting for several key signposts before increasing their production, including the return of oil demand growth, for OPEC spare capacity to be absorbed in the market, and for shareholder support to increase capital expenditure. Energy transition policies have little to do with this and, in fact, the Biden administration has explicitly stated its support for U.S. domestic producers to increase production.

Similarly, the LNG supply crunch that has compounded the energy crisis has its roots in commodity market cyclicality. It takes five years on average to build an LNG plant, so decisions to build would have needed to be taken right at the start of the new U.S. shale gas-to-LNG boom. Financiers would not have been convinced, as demand projections simply did not show a need for new capacity until the mid-2020s.

In the meantime, actors that do have the power to ease the global energy crunch, such as Russia, OPEC and yes, the U.S. oil and gas sector, can sit tight, reap fantastic rewards from the high prices, and enjoy the sight of commentators walking into the gigantic intellectual trap of blaming climate action for the market turmoil.

The risk here is that we fall for it. As BNEF has written elsewhere, there will be volatility all the way from here to net zero, as supply and demand of oil, gas and other commodities fall in and out of balance. Energy importers and suppliers must get better at navigating these cycles with long-term contracts and hedges. And through this volatility, policy makers will need to keep a laser focus on demand-side transition policies that chip away at society’s reliance on polluting fuels. 2022 will be the first big test of this resolve.

Political dysfunction

Our final risk for the energy transition in 2022 is the most serious: that the lofty ambitions of leaders returning from COP26 hit a political brick wall back home. This primarily concerns the United States, of course. The stalling of the Build Back Better (BBB) bill in December was a major setback for President Biden’s climate agenda, as that bill would have, among other things, extended tax credits for numerous clean technologies that need to be deployed in this decade.

There are silver linings: the legislated Infrastructure Bill provides funding for grids, EV charging, hydrogen and carbon capture. Also, U.S. states will continue to pursue their own net-zero transitions. But if a new BBB bill with major climate provisions cannot be passed, it will signal that even in the year 2022, a working political consensus on the low-carbon transition still does not exist in the U.S.

Fears of ‘greenflation’ are a factor here too, with the pivotal Senator Joe Manchin having expressed concern that U.S. consumers cannot afford to foot the bill for climate action.

COP26 bought the world’s climate diplomats one more year to come back with plans to get to 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming, but there’s a real chance that the world’s second-largest emitter will do the opposite: come back with no credible plan to meet its existing goals. This would surely take some of the pressure off countries, particularly developing ones, that are wavering on raising their own commitments.

So perhaps the biggest risk this year comes in the stories we tell about inflation and the cost of living. It is said that no one will vote to be poor and cold, but it remains true that the costs of inaction on climate change are higher than the costs of action. In a year of economic turmoil, we will need to be watchful for spurious arguments that amplify the message of climate action delay.