By Albert Cheung, Deputy CEO, Shantanu Jaiswal, Head of India Research, and Ashish Sethia, Global Head of Commodities, Energy & Environmental Markets, BloombergNEF

India has a claim to be the most important player in the global energy transition.

True, it isn’t the biggest emitter, doesn’t host the most renewable energy capacity and was only eighth in BloombergNEF’s country ranking of energy transition spending in 2022. But as the world’s most populous country, with a rapidly growing economy, an ambitious set of clean energy targets, a demonstrated ability to organize private capital, and burgeoning technological prowess, India has a chance to prove an increasingly important point: that you can simultaneously pursue a relentless growth agenda and capture the opportunities of the low-carbon energy transition.

This is arguably the hardest, most consequential frontier in global climate action today and one that many developing nations face. It’s all the more important because growth economies like India bear little responsibility for the carbon in the atmosphere today, but are projected to represent an outsized share of future emissions growth if no energy transition were to take place.

Yet, India may hold the keys to success for balancing economic growth and climate concerns – something it could demonstrate to the rest of the world as it enjoys the spotlight of the G-20 presidency.

If you travel to India today, you’ll find that its G-20 year is an immense source of pride. The G-20 logo can be seen everywhere – from roadsides and airports to government buildings. There is an air of expectation, and the energy transition is a key topic where the country is anticipated to show progress and step up its ambitions.

G-20 signage in New Delhi

Source: Prakash Singh/Bloomberg

There are several opportunities and success stories India can show to arriving G-20 leaders, as well as challenges it must tackle after they depart. These experiences can also serve as a template for other developing countries hoping to capture the opportunities of the low-carbon energy transition.

Scale opportunity: Accelerating clean power

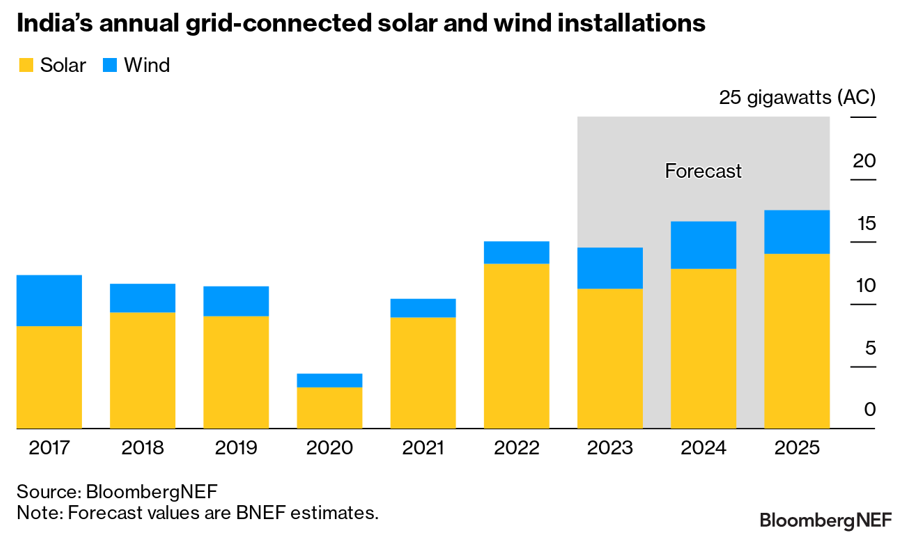

India is already a global leader in the construction of wind and solar power. The 109 gigawatts it currently has installed is equal to 5% of the global total, putting it behind only China, the US and Germany. Its auction and tender programs are among the world’s most successful and have helped it build subsidy-free renewable energy capacity with some of the lowest costs.

India’s rising population and surging power demand present a rich opportunity for clean energy deployment. We estimate the country will add 49GW of solar and wind power over the course of 2023-25, but may struggle to reach its target of 50% non-fossil-fuel-fired power generation capacity by 2030 due to some significant bottlenecks, including challenges with land acquisition, grid connections and offtake. Government action to relieve these obstacles and boost the market for clean energy power purchase agreements could help accelerate the low-carbon transition.

At the same time, India is pursuing a strategy of supporting domestic manufacturing by raising import barriers and subsidizing domestic production. So far, $8.5 billion worth of so-called production-linked incentives have been allocated to companies for the manufacture of solar, battery energy storage and electric vehicle technologies on Indian soil. Other programs, notably the Approved List of Models and Manufacturers for solar power, aim to restrict buyers from using foreign equipment.

In an era where countries are competing to capture more of the economic value-add from the energy transition while securing crucial supply chains, India doesn’t plan on being left behind. The key will be to balance this desire for industrial value creation against the need for a fast and cost-effective transition.

Growth opportunity: E-mobility and energy storage

Electric vehicles and energy storage sit in a second category of opportunity: where the direction is clear, but the inflection point (at least for larger vehicles and grid-level energy storage) hasn’t yet been reached.

In stationary energy storage, our latest forecast predicts 20GW (or 67 gigawatt-hours) of installed capacity by 2030, up from around 56 megawatts today, and government projections indicate even greater potential. The rise of ‘complex’ renewable energy auctions – where power delivery is being made more dispatchable – will drive adoption, as will energy storage-specific tenders. However, other mechanisms would accelerate adoption further, such as financial incentives, grid mandates and even the development of ancillary service markets, which have helped to boost revenue for storage developers in other markets. While the default assumption is that lithium-ion battery technologies will dominate, there is significant interest in pumped hydro and other next-generation storage technologies too.

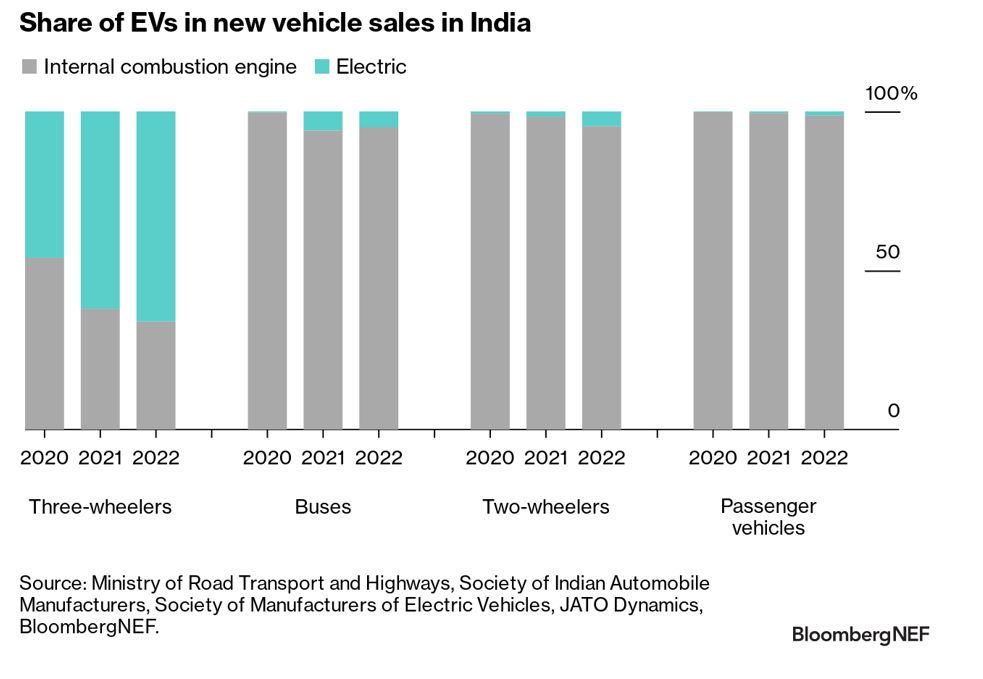

For EVs, the inflection point is approaching. Annual EV sales in the passenger vehicle and two-wheeler segments tripled in India in 2022, and the penetration of EVs in new passenger vehicle sales breached 1% for the first time. For two-wheelers, the share is now close to 5% and for three-wheelers it is a whopping 66%. Rising EV adoption in commercial vehicle fleets is also an encouraging sign.

The government is deliberating on how to follow up its FAME II incentive program once it expires at the end of this fiscal year. While more generous upfront subsidies are unlikely, further tax incentives could help push passenger EV penetration over 5% in the next few years, and experience from other markets suggests this could provide enough of a signal for more automakers to crowd in.

Here India faces a key challenge common to developing economies: without much of a premium car segment to speak of, there is no easy leapfrog to early adoption. Instead, India’s automakers must tackle the affordable mid-range market immediately, with cost, design and usability at front of mind. Tata Motors has already had notable success, accounting for 85% of passenger EV sales in India in 2022 thanks to the momentum of its Nexon and XpressT models. Other automakers will follow its lead. BNEF has tracked around $5 billion in investment commitments from auto manufacturers keen to ramp up EV production in the country, including Tata, Maruti Suzuki, Hyundai and Kia.

This manufacturing push also extends to batteries to power EVs, with companies including Reliance and Ola having announced investments in battery factories supported by government incentives. The recent discovery of a large lithium resource in the state of Jammu and Kashmir will only add fuel to the excitement around this sector.

BNEF is working alongside the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) and the governments of India, the US and UK on the Zero-Emission Vehicles Emerging Markets Initiative (ZEV-EM-I) to support an accelerated transition to ZEVs in India.

Next horizon: Industrial decarbonization and hydrogen

India has tried to shore up its manufacturing sector and exports under the ‘Make in India’ campaign over the past few years. At a time when geopolitical and technological landscapes are shifting, this is an immense opportunity. However, the success of India’s industrial exports sector will be determined both by its cost-competitiveness and its carbon footprint.

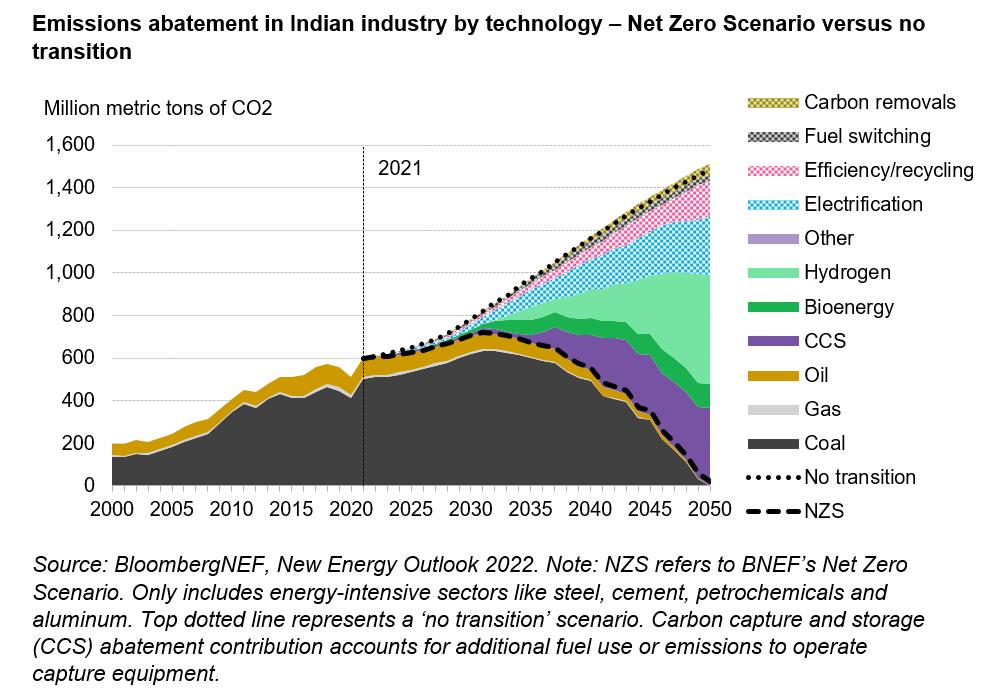

In a hypothetical ‘no transition’ scenario, India’s carbon emissions from energy-intensive industrial sectors (including steel, cement, aluminum and petrochemicals) would more than double between now and 2050. By contrast, a focus on growing green hydrogen demand, developing carbon capture and storage projects, and electrifying industrial processes could put Indian manufacturing on a pathway to net-zero emissions by 2050.

As more of India’s key trading partners start to consider embodied emissions in their trade policy, industrial companies in India will need to begin incorporating low-carbon technologies and processes into their capital expenditure decisions. As in other parts of the world, hydrogen is the technology generating the most excitement. India’s National Hydrogen Mission provides for $2.4 billion in subsidies for clean hydrogen production, electrolyzer manufacturing and pilot projects from 2025-2030, and discussions have revolved around a possible target for 5 million metric tons of clean hydrogen production by the end of the decade. Rapid decarbonization to 2050 would drive India’s total demand for green hydrogen to nearly 11 times this goal, at 53 million tons, according to BNEF’s latest Net Zero Scenario.

However, a lack of demand-side policy means there are few incentives for heavy industry to adopt clean hydrogen, raising the possibility that the Mission’s goals may be missed. More robust industrial decarbonization measures, such as the mandated use of hydrogen, demand-side subsidies, infrastructure development and public procurement of green products could meet the dual objectives of scaling up India’s green hydrogen sector while kickstarting the process of industrial decarbonization.

BNEF has been supporting the work of the Climate Finance Leadership Initiative (CFLI) to help develop the green hydrogen industry in India.

A key question for the G-20 and B-20: International finance

India is already a major destination for foreign direct investment in the clean power transition but rising interest rates, foreign exchange risk and high inflation are creating challenges for financing renewables in the short term.

Some $363 billion of investment in new generation technologies is needed through 2030 to meet the Central Electricity Authority’s optimal capacity mix projections, according to BNEF estimates. Out of this, $241 billion is required to build solar and wind power plants, and another $26 billion to build battery storage projects.

India’s renewables sector plays host to plenty of foreign capital, but eight of the world’s top 10 pension and sovereign wealth funds (as ranked in 2021) have yet to invest equity in the sector. Power producers will need to tap into these new or underutilized sources of capital to meet the country’s 2030 goals. India’s rising power demand and government support for clean power do put it in a strong position to attract more foreign capital, especially as financiers face pressure to do more on climate change.

Yet, clean power is just the start. Across the full scope of the energy transition, India would need to invest $221 billion on average each year to 2030 to get on track for net-zero emissions by mid-century, according to BNEF’s Net Zero Scenario. This includes money for renewables and energy storage projects, electric vehicles and associated infrastructure, and other areas including hydrogen and carbon capture. India spent a mere $16 billion on these technologies in 2022.

It is perhaps here that this year’s multilateral meetings can move the needle the most. As a forum for convening international and domestic leaders in both the private and public sectors, the upcoming B-20 and G-20 summits have the potential to build knowledge and lower the barriers to deployment of new clean energy technologies, while bringing in both capital and know-how from international investors.