By Kyle Harrison, Head of Sustainability Research, BloombergNEF

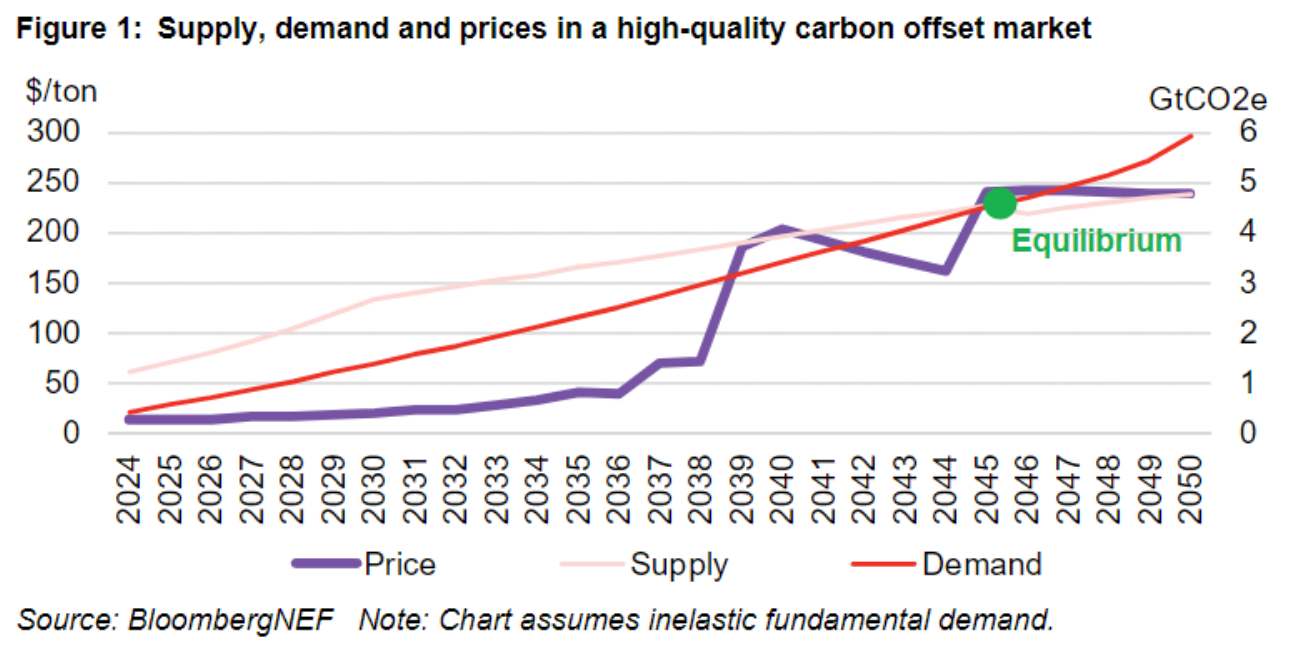

The role of carbon offsets, or tradeable verified emission reduction credits, has historically been limited with the UN-backed standards body — Science Based Targets Initiative or SBTi — restricting their use to cover a small volume of ‘residual emissions’. Its announcement to allow wider use of offsets means that a high-quality voluntary carbon market is one step closer. Annual demand for these offsets could reach 5.9 billion tons, prices could peak at $243 per ton and annual value could top $1.1 trillion (Figure 1).

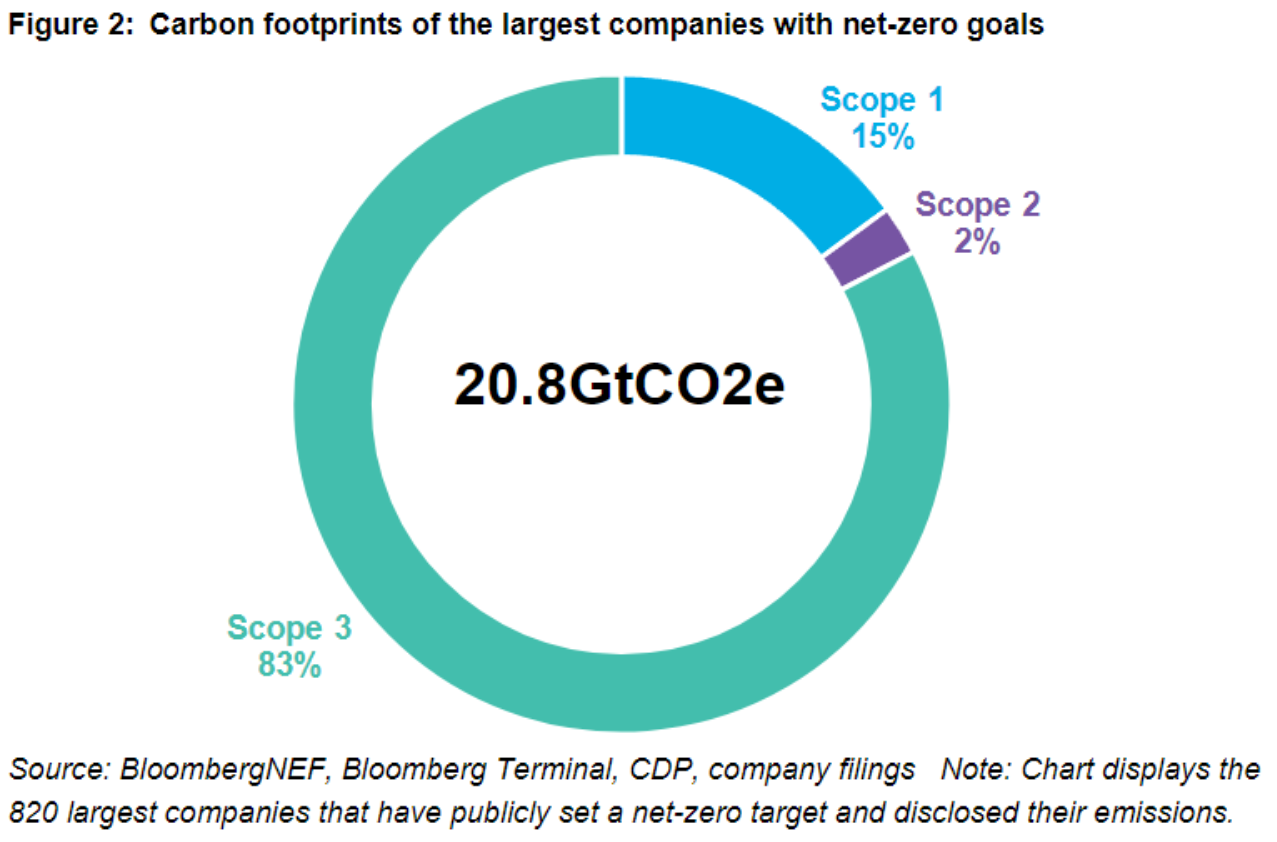

SBTi brings together the largest group of corporations that have Paris-aligned climate commitments. Its decision to allow companies to use carbon offsets to neutralize their Scope 3 emissions — which come primarily from suppliers upstream, the use of products by customers downstream and corporate travel — changes the game substantially. These emissions make up the largest chunk of a typical company’s carbon footprint and are the hardest to measure and reduce.

Nearly 3,100 organizations have set or committed to set a net-zero target as part of SBTi to date, which means they intend to fully reduce and offset their emissions by 2050 or earlier. As part of its guidance for net zero, SBTi mandates that companies must reduce their emissions across the value chain by at least 50% in 2030 and 90% in 2050. Only then can they neutralize any remaining emissions with carbon offsets, which strongly limits both demand and the near-term viability of credits.

For companies with high operational emissions, classified as Scope 1 and 2, SBTi’s guidance may be achievable. They can purchase clean energy — corporations purchased a record volume in 2023 — electrify their vehicle fleets or implement efficiency measures to reduce energy consumption. For companies with heavy Scope 3 emissions however, such as consumer goods companies, industrials, airlines and energy companies, this becomes a much more daunting task requiring a complete business model change.

BloombergNEF estimates that the carbon footprint of the 820 largest companies with net-zero goals totals 20.8 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e). Scope 3 emissions make up a whopping 83% (17.2GtCO2e) of that footprint (Figure 2).

In a survey conducted by SBTi in February 2024, over half the respondents felt that Scope 3 emissions — both in terms of measuring and reducing — were the biggest barrier in setting net- zero targets. The limited use of offsets allowed to reduce emissions was a big driver in SBTi revoking its acceptance of net-zero commitments from 140 companies as they failed to show progress on their targets. It was also likely a big driver of SBTi’s latest announcement to allow offsets for Scope 3 emissions.

Realizing a high-quality market

While some details of SBTi’s announcement are awaited (there are reports of dissent within SBTi on the changes), a demand boost is almost certain, and that will bring a high-quality voluntary carbon market closer. In this market, supply would be limited to a smaller pool of carbon offsets, but they can serve as a legitimate backstop for net-zero goals and be relied upon much more by

companies.

In its Long-Term Carbon Offsets Outlook 2024, BloombergNEF estimates that without limitations from SBTi, demand for carbon offsets in a high-quality market would grow from 164 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent today to 1.37GtCO2e in 2030 (Figure 1). Demand would peak at 5.9GtCO2e in 2050. The market would be oversupplied in the coming years as most net-zero targets are early stage, demand would catch up in later years and exceed supply in 2046. Prices for carbon offsets would be low in early years, reaching $20/ton in 2030, but would peak at $243/ton in 2046 when the market becomes undersupplied. This is far higher than current averages, which sit around $13/ton.

This would create a massive need for investment into the supply side of the market and trading infrastructure to ensure proper liquidity. BNEF estimates the annual value of a high-quality voluntary carbon market would peak at an astounding $1.1 trillion in 2050 – far higher than current market estimates of $2 billion.

Next steps

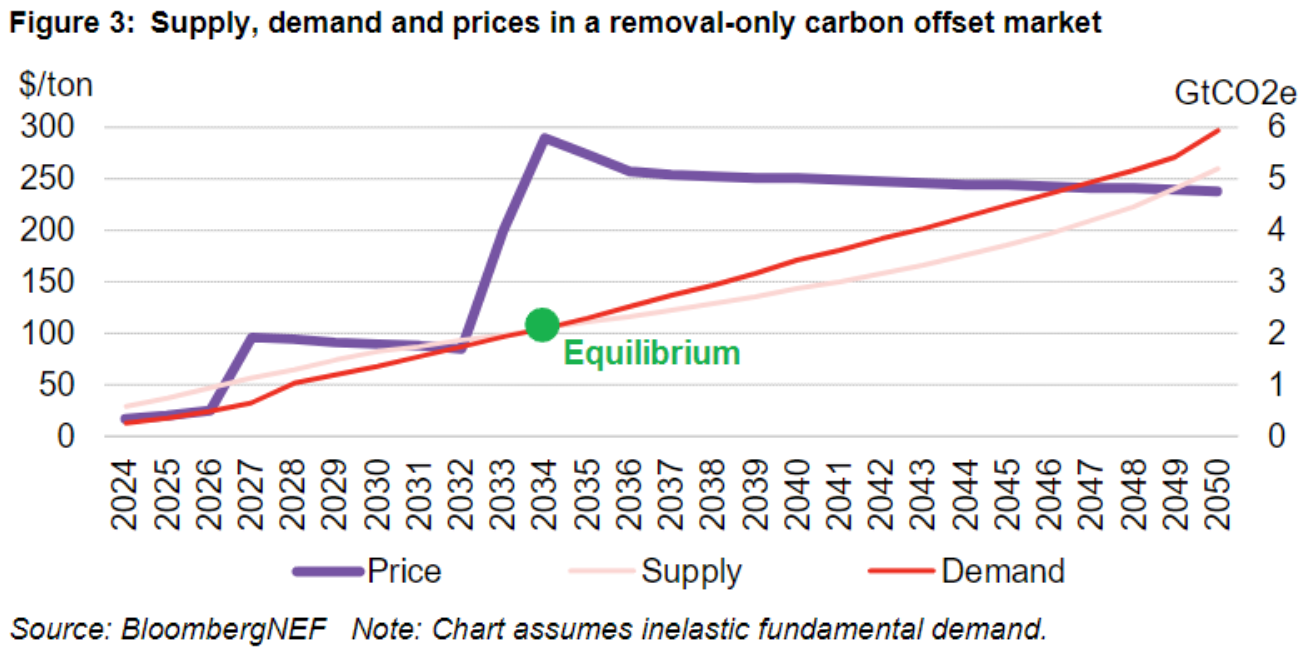

SBTi’s decision to allow offsets in addressing Scope 3 emissions on the road to net zero opens the door for review of its other guidance too. The most controversial of these is SBTi’s restriction for companies to only use removal carbon credits to make a net-zero claim. While SBTi will rely on other integrity initiatives to evaluate individual projects, it has been vocal in its opposition of avoidance credits from sectors like avoided deforestation, clean cook stoves and clean energy. This heavily limits offset supply in early years.

A removal-only market could certainly drive more impact in the long run. Technology based carbon sequestration is easier to measure, has less questions around impact and often can be considered more permanent. However, most carbon removal technologies, such as direct air capture and bioenergy carbon capture and storage (BECCS), are prohibitively expensive today and supply is limited. BNEF estimates a removal-only voluntary carbon market would be undersupplied by 2034 – 12 years earlier than a high-quality market (Figure 3). Prices would shoot up to $96/ton as early as 2027 and $290/ton in 2034, pushing most buyers out of the market. A removal-only market is a north star for the impact carbon markets can have, but its fundamentals aren’t grounded in reality.

SBTi could very well adjust its stance on carbon avoidance credits in the long run. As the loudest and most authoritative voice on corporate climate action, its latest announcement regarding Scope 3 emissions shows that it listens to its constituents. Future decisions could bring us even closer to a high-quality voluntary carbon offset market.