By Derrick Flakoll, Brenna Casey, Sharon Mustri and Julia Attwood, BloombergNEF

The US Environmental Protection Agency’s long-awaited proposal to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from fossil-fuel power plants is here – and it’s capable of spurring huge carbon capture additions for fossil-fuel plants that stay online.

The EPA designed this latest round of rules to overcome the legal barrier that blocked both the Obama Administration’s Clean Power Plan (CPP) – the first US regulation designed to limit climate pollution in the electricity sector – and the Trump administration’s less-aggressive successor, the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule.

In West Virginia v. EPA, the US Supreme Court ruled that ACE and CPP had overstepped by attempting to regulate overall carbon emissions from the power sector. Now, to avoid the wrath of the courts, the EPA is focusing on its well-established authority to require the “best available” pollution control technologies under the Clean Air Act.

What happened

Specifically, the EPA is pushing to reduce – though not eliminate – fossil-fuel-powered electricity emissions by effectively requiring carbon capture equipment for most coal plants that remain in service by 2040. For smaller or intermittently operational coal plants, the EPA requires “clean fuel co-firing” instead – by replacing 40% of heat input with natural gas.

The rules also require gas plants with a capacity of at least 300 megawatts and a capacity factor of at least 50% to either install carbon capture equipment by 2035 or replace all but 4% of their fuel by volume with clean hydrogen by 2038. Plants can only escape these requirements by committing to retire by the 2030s.

The EPA designed its proposal to project flexibility and pragmatism – and to undermine charges that it is trying to shut down the fossil-fuel energy sector. The rules mostly exempt gas-fueled ‘peaker’ plants that provide energy when other sources of power are scarce, as well as coal plants that commit to retiring by 2030 (or by 2035, if they run at only 20% of capacity). Regulations only begin phasing in during the 2030s in general, and states have some flexibility as to how they implement the EPA’s requirements.

The clear effect of the rules would be to increase costs for fossil-fuel-powered electricity at a time when clean energy is cheaper than ever. Many developers and utilities will find it cheaper and less risky to replace their coal or gas with solar and wind rather than retrofit to meet requirements. The EPA itself projects that the rule should result in 18 additional gigawatts of coal-plant closures by 2040.

That very expense is also the biggest threat to the rule’s legal standing, however. The EPA can only require usable and affordable technologies, and few fossil-fuel power plants in North America have been able to sustain operations with carbon capture equipment.

Despite the well-established science of carbon capture and storage, its novelty in the electricity market is certain to attract lawsuits next year when the final rule is issued – which the EPA-skeptical Supreme Court could very well sustain when the case eventually reaches them, likely years later.

State of the market

There are only two commercial coal plants with CCS currently supplying the US grid, which together provide a total capture capacity of 0.07 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. There are no natural gas plants using CCS that are commissioned at scale. Yet this could be about to change: BNEF’s latest market outlook projects an 99.7% growth in coal and gas CCS assets by 2030, to reach 30MtCO2 per year – even prior to the EPA ruling.

BNEF calculates that the levelized cost of electricity for new-build coal and gas plants coupled with CCS is $142 per megawatt-hour and $80/MWh, respectively, which is 43-45% more expensive than running the power plants unabated. Retrofitting costs are also estimated to be marginally higher than for new build.

Outcome

The regulation will push 126GW of coal to retirement over 2023-2035, or an average of 18GW annually, according to EPA modeling. This represents a 38% increase from historical yearly retirement rates and, by BNEF’s calculations, an emissions reduction of 255MtCO2 per year.

That said, the EPA estimates that 104GW of coal would retire from 2023 to 2035 (15GW annually) even without the new rules. The regulation mostly pushes coal to close earlier than currently planned, rather than causing more plants to close, and the EPA calculates that the proposed rule only results in 18GW of net additional coal retirements by 2040.

An estimated 12GW of coal-fired power will remain operational after 2040 and will be retrofitted with CCS, despite its being more expensive than other carbon-compliant alternatives, like fuel switching or transitioning to renewables. BNEF estimates this to add about 1.05 billion metric tons of CO2 per year in CCS capacity in the US.

Rather than a mandated a switch to renewables, many developers are likely to run the numbers and conclude that stranding a coal asset is still the path of lower cost and risk compared to investing in new technologies to keep an old plant running.

A significant portion of these plants are close to a proposed CCS hub, which will allow for a swift integration with transport and storage networks. Plants not proximal to a developing hub will require a transport and storage build-out, which will further tack up already expensive retrofitting costs. Lack of accessible infrastructure may instead push plants toward retirement, which will have disproportionate effects on states with sub-par storage aquifers, like West Virginia.

BNEF’s take

Until now, the US has relied on ‘carrot’ policy-making to accelerate the energy transition. The IRA, for example, incentivizes the supply of clean technologies like CCS and hydrogen through a production tax credit. These solutions, however, still need ‘sticks’ to spur demand as they scale, aligning both companies’ and markets’ needs to make low-carbon solutions economical.

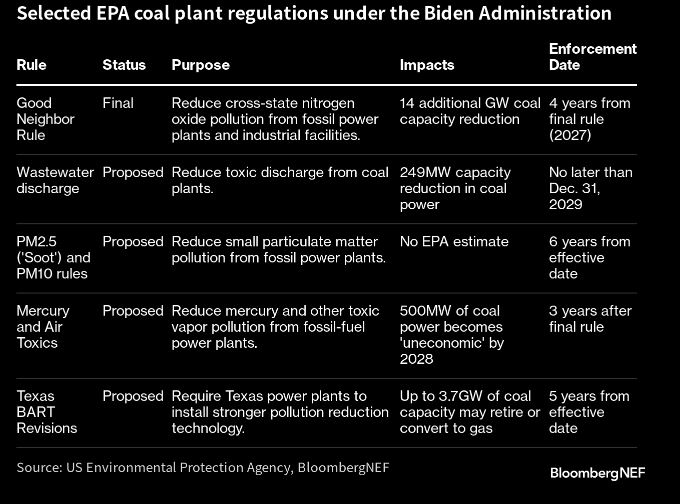

In the years and years of regulatory uncertainty that will follow legal challenges to this rule, the EPA’s proposal creates a market signal, especially when stacked on top of other regulations – like the PM10 and PM2.5 (soot), wastewater discharge, Mercury and Air Toxics, and “Good Neighbor” rules – that coal fundamentally is a dying industry. The underlying economics more than support this notion.

The 2021 UK ruling to decommission unabated coal spurred investment into technologies like bioenergy carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and hydrogen. This is a technological shift that could be paralleled in the US. If BECCS is an abatement method of choice, developers could capitalize on a second revenue stream, derived from the voluntary market, to make the project economically viable. Careful carbon accounting would be needed to ensure the process truly qualifies for a carbon offset.

This rule will no doubt spur significant opposition: lawsuits will immediately target and possibly stall the EPA’s final power-plant emissions rules, and their leisurely timeline – less aggressive than the Biden Administration’s 2035 target for 100% clean power – ensures that market factors will remain the primary driver of fossil-fuel-plant shutdowns.

Over 50GW of coal generation, roughly a quarter of the US fleet, is scheduled to retire by 2029 regardless. But the years of regulatory uncertainty this rule creates will only strengthen the market case for switching from increasingly risky fossil-fuel assets to renewables sooner rather than later, especially since this is only one among many EPA rules – many based on well-established EPA programs and authorities – designed to force fossil-fuel plants to cut pollution or shutter.

Assuming no plant closures are duplicative between rules, the EPA already projects that its regulations will drive up to 18.5GW in additional coal retirements by 2030, even if fossil-fuel greenhouse gas restrictions never go into effect. Some of these rules may be struck down, but it’s unlikely that all will. Together, they send a powerful signal that the end of coal power is near.