By Julia Attwood, Industrial Decarbonization Specialist, BloombergNEF

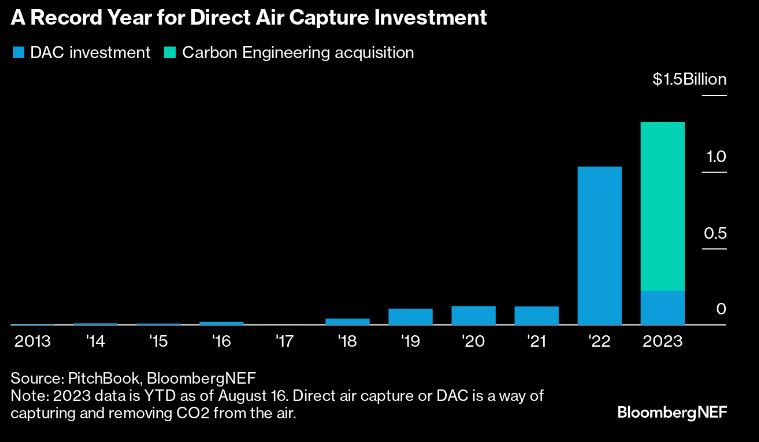

Warren Buffett-backed Occidental Petroleum (Oxy) formalized its long-term relationship with Carbon Engineering – a provider of direct air capture or DAC solutions – by announcing that it would buy the startup for $1.1 billion. This could change the long-term trajectory of the technology though very little will change in the near term. The DAC market could be worth $150 billion per year by 2050, according to BNEF.

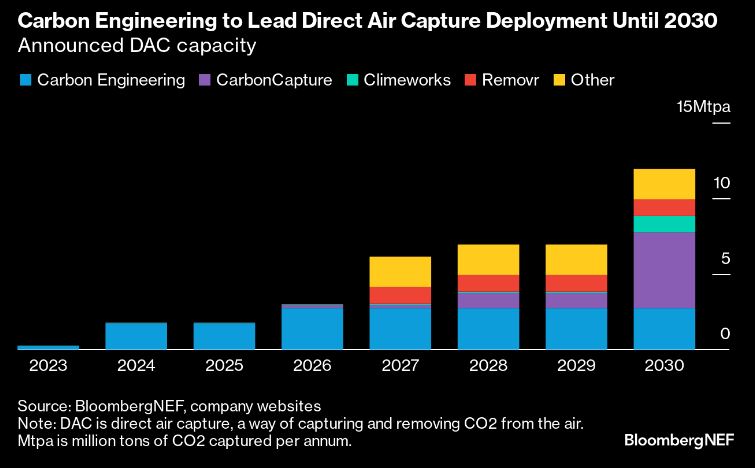

Oxy has ambitious targets to grow its DAC business. It has announced plans to build 100 plants by 2035, and expects the business unit to grow to the size of its chemicals arm in the next decade. Buying Carbon Engineering will give it greater access to DAC technologies and a solid pipeline of projects to kick-start its deployment goal.

DAC technologies are still seen as early-stage, with the true proof of concept considered to be a plant with 0.5 to 1 million tons of CO2 captured per year. Most of the plants at this scale are not due to come online until 2025 or 2026. This makes the decision to buy seem premature, especially given that there was already a close partnership between the two companies. Oxy may have felt that it already had convincing proof of the company’s technology, or believed that its valuation would spike after commissioning a successful, large-scale plant, pushing the startup out of its price range.

While this is a vote of confidence for the DAC market, very little will change in the short term. Oxy was already using its supply chain and capital to help Carbon Engineering scale, and long timelines for construction make a rapid increase in capacity before 2026 unlikely. This could change the long-term trajectory of DAC technologies, however. Carbon Engineering uses a liquid solvent for capture, while its other major competitors use solid sorbents. The solid technologies can have a lower energy intensity and could eventually reach lower costs, making them the more obvious choice for future plants. If Oxy can deploy Carbon Engineering’s system faster than its solid competitors, that could shift the technology balance in favor of liquids.

Oil companies see DAC as a saving grace for climate

Just as European oil companies began investing in wind and solar in the mid-2010s, American oil majors are looking for a climate pivot. Many are investing in DAC, and carbon capture more broadly, as a first step for their low-carbon units. Exxon bought Denbury, the owner of the largest CO2 transport network in the US for $4.9 billion in July, and Chevron has also invested in Carbon Engineering. With more than $1 billion flowing into DAC startups last year, this is an opportunity for Oxy to own a piece of a growing market with climate benefits.

DAC, and specifically Carbon Engineering’s technology, also fits well with Oxy’s expertise. Carbon Engineering’s liquid solvent contains calcium oxide and potassium hydroxide, and needs high temperature heat to recover the CO2 from the solvent. This typically means that natural gas would be used to power at least a portion of the plant’s equipment, though Oxy and Carbon Engineering have announced an agreement to supply the site with solar power. Oxy is a large manufacturer of potassium hydroxide and an oil and gas producer, making it well suited to supply Carbon Engineering’s plants.

Both Oxy and Carbon Engineering were pioneers in the capture and storage sector. Oxy states that it stores up to 20 million tons of CO2 per year in geologic reservoirs. The logistics of storing CO2 have plagued early carbon capture projects, and are a potential risk for DAC companies selling carbon offsets on the basis of removing CO2 from the atmosphere permanently. Oxy’s expertise should help to smooth this aspect of the deployment process.

$100 per ton

Carbon Engineering was one of the first DAC companies to claim it could reach the holy grail of $100 per ton of CO2 capture costs. At this price, DAC would be comparable to the carbon price in more mature markets, such as the EU and Canada, making it a viable option for emitters who cannot easily abate their CO2. No company has yet demonstrated these costs, with the average cost of a DAC credit currently sitting at $1,100/tCO2 and the highest hitting over $2,200/tCO2. Companies, including Oxy and Carbon Engineering, are betting that scale and modular designs will help them lower costs to around $400/tCO2 by 2030, and hit $100/tCO2 by 2050.

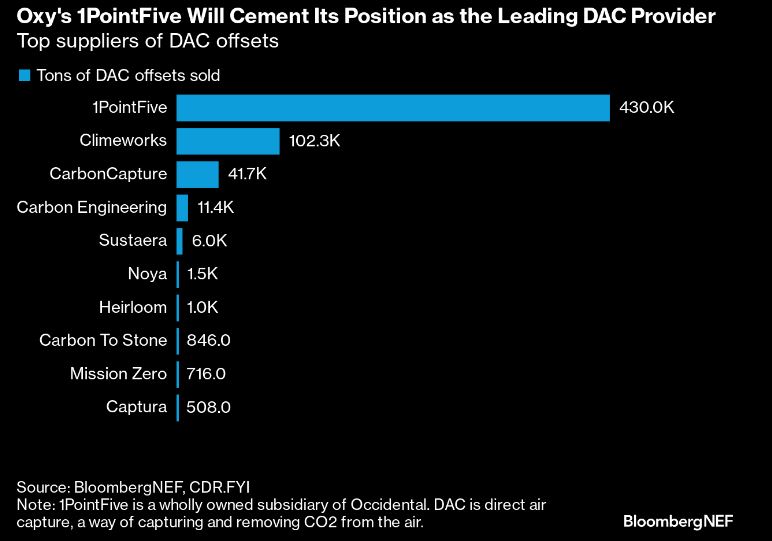

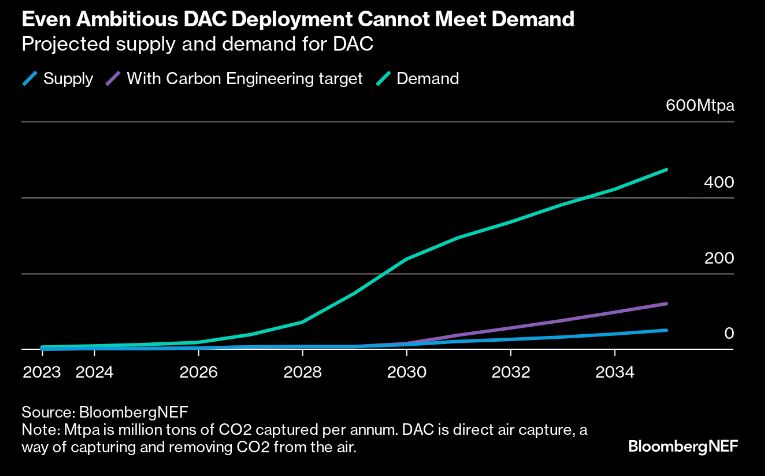

BloombergNEF analysis shows that even at aggressive deployment rates, reaching $100 will be difficult. The largest commissioned DAC plants today only remove around 4,000 tons of CO2 per year. If Carbon Engineering achieves its current pipeline, it will be the largest DAC provider until CarbonCapture’s Bison plant reaches full capacity in 2030.

The two companies have worked closely together since 2019, with Oxy’s wholly owned subsidiary 1PointFive working with Carbon Engineering to develop the Stratos project – its first large-scale plant, and the model for the South Texas DAC Hub. The plant is due to be commissioned in 2025, with an initial capacity of 0.5 million tons of CO2 captured per annum (Mtpa), potentially rising to 1Mtpa. DAC companies typically pre-sell some of the offsets they expect to generate in order to finance construction and demonstrate to lenders that there will be reliable revenue streams on completion. The credibility that Oxy brings to the project and the scale of its plans has made it the leading supplier of DAC removal offsets. Adding Carbon Engineering’s independent project pipeline to its total will further increase its lead over DAC competitor Climeworks, which has been taking a more incremental approach to demonstrating its technology.

Carbon removals demand is growing faster than supply

The largest buyers of DAC offsets today are technology companies and airlines. Tech companies have relatively small direct emissions and the resources to pay thousands of dollars per ton of CO2 for the promise of creating a thriving removals market. Airlines have extremely hard to abate emissions and no cheap options: sustainable aviation fuels also come with a hefty premium.

However, demand for DAC is still likely to grow, despite these high prices. It offers one of the highest quality carbon offsets available. If regulators and investors become increasingly stringent about what would count as an offset, current buyers in the voluntary carbon offset market could turn to DAC. Eventual lower costs will also widen the pool of companies able to afford DAC as part of their net-zero strategy.

Even including Carbon Engineering and 1PointFive’s ambitious goal to build 70 plants with a capacity of 1Mtpa by 2035, supply is nowhere near demand in BNEF’s outlook. This will lead to higher prices in the short term and leave a great deal of room for growth. Assuming the market reaches a projected 1.4 billion tons of DAC supply per year by 2050, and that costs fall in tandem with this increase in scale, the DAC market could pass $150 billion per year in value. With so few companies developing DAC technologies, owning (and licensing) an effective one could be extremely valuable.

Policymakers ready to subsidize DAC

Countries are also interested in stimulating a high growth DAC market and even buying the offsets themselves, though so far only the US, Canada and Norway have opened their wallets. The Inflation Reduction Act included a substantial increase to the US’s flagship carbon capture subsidy (45Q). Direct air capture plants will now be able to claim $180 for every ton of CO2 stored for 12 years, up from $50 before the act. Norway has proposed a similar subsidy, offering $186/tCO2 (2,000 kroner) for 10 years. Canada provides a 60% tax credit for DAC capex.

Oxy and Carbon Engineering in particular benefited from a multi-million dollar grant from the US Department of Energy. Only a few days before the acquisition was reported, the administration announced that two DAC hubs, Climeworks and Heirloom’s Louisiana project and the Oxy-Carbon Engineering South Texas Hub, would share $1.2 billion in funding. Since the two plants will have the same capacity (1Mtpa), it is likely that they are splitting the funding, receiving $600 million each, though no specific amount has been disclosed. This huge injection of almost no-strings-attached capital will go a long way to shoring up these projects and the startups behind them while the industry struggles to overcome supply chain and logistical issues that have caused significant delays.

Permitting challenge

While the DAC market can certainly use more investment, the largest problem facing developers is permitting. The US Environmental Protection Agency currently has 118 permits for Class VI wells (the type that are used to store CO2 permanently) pending. There have been estimates that this will create a six-year waiting list for approvals. Even in states such as North Dakota, which have primacy over their permitting processes and can avoid the long federal process, carbon capture projects are struggling to get approved. Summit Carbon Solution’s $5.5 billion project was recently denied a pipeline permit in the state. There are also reported delays in acquiring the land and pore space for DAC projects to store their CO2.

Without access to transport and storage, DAC developers will need to turn to utilization options, most of which are likely to return the CO2 to the atmosphere. This reduces the climate benefit, the value of the 45Q credit, and eliminates any revenues from carbon offsets. A great deal of the business case for DAC rests on storage.

Carbon Engineering may now be well-positioned to deal with storage woes, as it will have greater access to Oxy’s depleted fields, which can be repurposed to store CO2. However, while the Stratos project originally planned to use its CO2 for enhanced oil recovery or EOR, and could also turn to e-fuels or sequestration and offsets, the South Texas Hub intends to drill new Class VI wells for sequestration, hitting the same permitting hurdles as the rest of the industry.